Nowadays most generals are extravagant in their use of ammunition but parsimonious with the lives of their troops. Not so during WW1. By the end of WW1, the British Commonwealth had suffered more than 1.1million deaths and countless millions more maimed and injured. Most of the deaths on the last day occurred between the Armistice being signed at 5:10am within a railway carriage in Compiegne Wood and the ceasefire coming into effect at 11am that same morning. How could 10 000 soldiers become casualties that day when the Deed of Cessation of hostilities had already been signed?

For those with a conspiratorial disposition, be assured that there was no significance in the fact that the time and date of the cessation of hostilities comprised the number eleven. This was pure happenstance. The German delegation led by a civilian Matthias Erzberger had arrived some days earlier to conclude a peace treaty. In spite of the Allies being aware that the German’s mandate was peace at any cost, the Allies under Marshal Ferdinand Foch was truculent and in no mood to make any concessions to the Germans. This truculence was to delay the peace by three days.

Main picture: Carriage in which the Deed of Armistice was signed

Unlike the plucky German soldiers who had endured four years in the trenches, this coterie of Germans was surprisingly servile, despondent and amenable. Their undogmatic demeanour was foistered upon them due to the dire straits in which Germany found itself. With starvation and penury stalking the civilian population and Bolshevik revolutionaries taking control of the capital ships of the Kriegsmarine, Germany was prostrate before the advancing Allies.

Postcard of the carriage in which the Armistice was signed

The reason for Foch’s churlish attitude and uncompromising stance towards the Germans was due to France’s devastation – they lost the most soldiers during WW1 – but more personally having lost a son and a son-in-law to the invading German forces. When Foch first met the German delegate he is reputed to have brusquely enquired, “What do you want from me?” What an unwelcoming opening gambit?

In 1917 Germany executed a master stroke, one whose dividend must have exceeded their wildest expectation. Living in exile was an unknown Russian revolutionary by the name of Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, better known by the nom de guerre of Lenin. As an avowed communist, revolutionary, politician and political theorist, his mandate was to free the working class man from the predations and privations of the war. In his warped political mind, all events of whatever nature formed part of the class struggle; thus his earnest desire for peace at any cost.

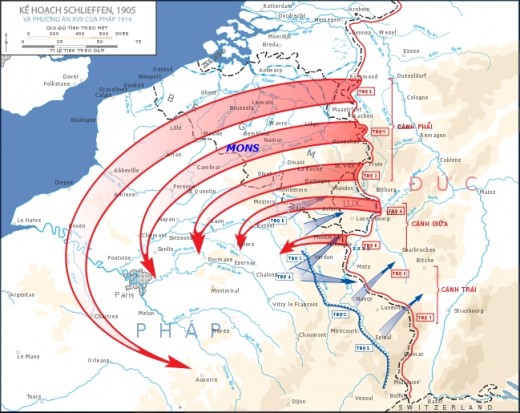

The original Schlieffen Plan

In spite of the free election indicating that the Communists lacked support within the community, Lenin did what all good revolutionaries do: he unilaterally seized power; hence the polemic of the two stage dogma of the usurpation of power arose. He rapidly signed a humiliating peace treaty with the Germans thereby freeing up a million German troops who would immediately be available for transhipment across Europe by rail to launch a new offensive against the Allied forces in France.

Part of the reason of the German’s haste in launching this offensive in March 1918 was that Woodrow Wilson had reluctantly instructed the Americans to enter the fray after the sinking of passenger ship, the Lusitania. Like the rest of the war-weary Europe, Germany was down to the last few million suitable men. The main thrust of the attack in the west fell against the Commonwealth forces at Amiens and the French forces on the Marne.

Two trains at the railway siding at Compiegne – one being Foch’s personal one & the other one being used by the German delegation

Unlike the gridlocked trench warfare of the previous four years along the 450 mile static line, this was a campaign of movement. The first wave of German forces overwhelmed the British forces, throwning them into headlong retreat and abject disarray. In full flight, they were unable to curtail the onward rush of the German forces. Finally General Haig was forced to issue his do-or-die, backs-to-the-wall, to-the-last-man speech. In this manner he rallied his forces and terminated their headlong flight.

Aiding and abetting the Allied cause was the fact that by this time the German advance was spent.

In the meantime, the American doughboys – the precursor to the more recent GI nomenclature – were disembarking by the shipload in the French ports. The term doughboy was an informal, non-pejorative name for members of the American Expeditionary Forces in WW1. It remained in use until the commencement of WW2 when it was rapidly substituted by the modern term GI.

US Troops – the doughboys – in France in late 1918

General John Pershing, the cocky American general, insisted upon his forces being an independent command in France. They were thrown into battle along the River Meuse. Adopting the now discarded tactics of 1914, they advanced into murderous German machine gun fire and lost 14 000 men on the first day.

During the respite given to them by the exhausted German forces, the English and French forces launched their own offensives. These surprisingly came upon a dispirited, disaffected rabble. Pockets of resistance still slowed the Allied advance but in the main, for once, they were able to maintain a steady pace against tepid resistance.

Wilfred Owens – The Soldiers Poet

With the Bolsheviks fomenting revolt at home in Germany, the disaffected German civilian population was restive and in no mood to countenance prolongation of the war. Meanwhile spring was transformed into a bitter beguiling summer in November 1918 of starvation and unrest. With culpability for the hardships being attributed to the military leadership, they sought to deflect this anger by appointing civilians to lead the peace negotiations.

In this manner, Matthias Erzberger was selected and sent to France to negotiate an honourable settlement. In a three vehicle convoy, they drove towards the Allied line near Hombliers with white flags flying. From there they were transported by train with blinds drawn to a woody railway siding at Compiegne in which General Foch’s personal railway coach was parked.

It was here that Matthias was to be “greeted” with the sullen ice cold mordant comments of Foch. Having to rely upon the French for telegraphs services, they did what any self-respecting negotiator would do: he read the German’s correspondence. In spite of being totally aware that the cards in the German’s hands were of inconsequential denominations unable to trump their Royal Flush, Foch was undaunted and unpersuaded to grant them any facile solution. His demands were extreme: the surrender and handing over of whole German fleet and Alsace-Lorraine, the occupation of the Saar, forfeiture of most guns, planes and artillery; in fact the total emasculation of the German armed forces.

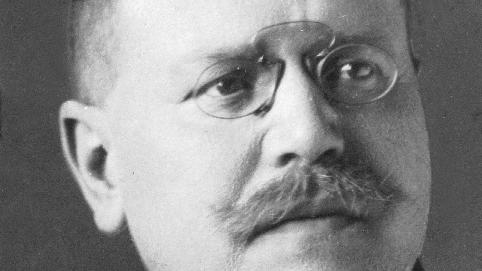

Matthias Erzberger

Matthias was devastated.

Finally three days later at 5:10 in the morning of the 11th November 1918, both parties signed the Deed of Armistice. To allow the message to be relayed to all the military forces affected, a time of 11am was agreed upon as being sufficient for its transmission and distribution. Within half an hour, the whole world was engaged in joyous celebration at the culmination of the war.

Scene near Mons, Belgium in November 1918

Except that the reality on the ground was very different.

The Allied generals and the Americans in particular had their own very different ideas.

During the first month of the war, the British forces had been based at a Belgium town of Mons. In the savage fighting in the area in late August 1914, the British had been forced into a humiliating retreat during which the cream of the professional British army was comprehensively destroyed.

The original Battle of Mons in 1914 during which the British forces were soundly trounced

Now it was the turn of the British to pulverise the Germans in retaliation to banish the ghosts of Mons. On the 10th November, the British commenced their attack on the town of Mons itself. The Canadians under General Sir Arthur Curry had the unenviable job of storming the bridge over the Sambre Oise Canal outside Mons which they did with alacrity, suffering only 30 deaths in the process.

The last British death on the 11th November to be recorded was that of Private George Ellison who, at 36 years of age, was one of the few survivors of the defeat at Mons in 1914. Over the intervening four years, the plucky George Ellison had seen his companions steadily whittled away as German bullets and shrapnel steadily took its toll. Finally with the end of the war no more than 90 minutes away and George now assured of returning to Leeds in order to be reunited with his wife, he was shot and killed at Mons. His finally resting place is at the allied cemetery at Nievalle, one grave amongst the hundreds of Commonwealth soldiers who died on that fateful day.

The grave of Private George Ellison, the lasst British soldier t be killed during WW1

Technically Wilfred Own, the preeminent British war poet had been killed five days earlier during the advance on Mons, but it was only on this day, the last day of the war, this his widow-to-be was informed in the uncompassionate prose of formal military jargon that Wilfred had been killed in battle forever silencing one of the new generation of poets.

Of all the idiotic battles on that day, the most imbecilic must have been the one at Stenay on the American sector. With 90 minutes before the ceasefire, the local American general demanded that his troops launch one last attack. His inane logic was that they needed to capture the showers so that the troops could get washed. Instead of biding their time & strolling into the town at 11am, 300 American casualties were sustained.

Ironically the last American to be killed was of German extraction, Henry Gunther at 10:59. So as not to have to shoot the advancing American soldier, the German machine gunner stood up and waved at Henry to indicate to him to stop his advance. When the American kept moving forward, he sat down and shot him dead, the last American death with one minute to the ceasefire

For their decision to attack within the last hours of the war, the American generals were rebuked by the American public. On their return they faced censure for “dereliction of duty” but ultimately no action was taken. Pershing was unrepentant for the 3000 casualties on that day, all avoidable.

General John Joseph Pershing

The last Frenchman to perish on that day was that of a messenger, Trebuchet at 10:50. The momentous message that he clutched in his hands was a notification of the impending ceasefire.

I am unable to ascertain whether there were any South African casualties on that day but their war’s end was unusual. At precisely 11am, a German machine gunner opposite the South African lines stood up, bowed formally and departed from the trench.

Finally the Great War, as it was then known, was over.

Celebrating the Armistice

Is a death on the last day of the war any more tragic than one on the first day? Maybe from a churlish clinical standpoint, they are not, but if the generals had ordered their men to bide their time in the trenches, 10 000 casualties would have been avoided that day.

Did those deaths and casualties advance the cause of peace?

Highly unlikely.

In fact, not at all.

However General Pershing would strenuously disagree with this line of argument.

He strongly maintained that the decision not to crush the Germans unequivocally and utterly would sow the seeds of another war, perhaps even more cataclysmic than the Great War.

History would vindicate his long view of history but not his decision to sacrifice and squander so many American lives on the very last day of WW1!

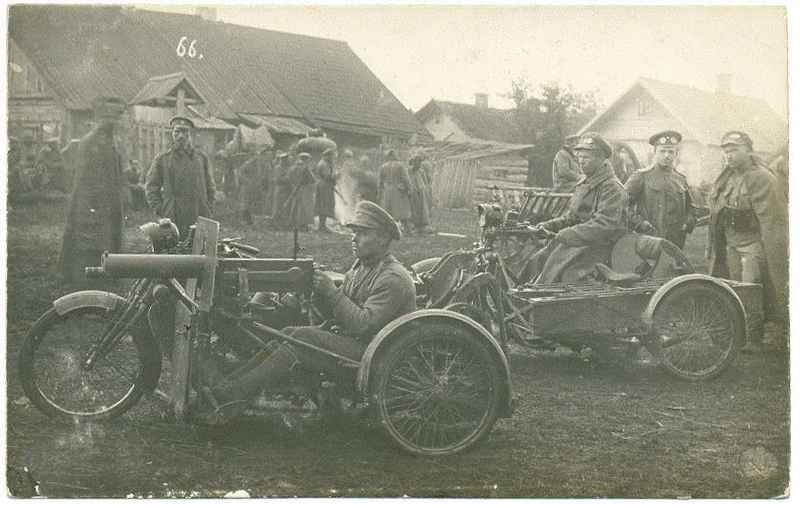

39th Tomsk infantry regiment with their motorcycle-mounted machine guns during WW1

Hitler would claim in his hate filed tome Mein Kampf – perhaps written in apocryphal hindsight – that he wept like a child when the news of the armistice was announced and swore eternal revenge. Personally I place no store in those comments written after the fact in 1923.

I still of the belief that the Great War was a travesty, a destroyer of the cream of manhood for what end. Morally it was reprehensible to condone the wilful slaughter of yet more soldiers on the last day of the war either for vanity and medals in the case of the Americans and for lack of foresight and EQ by the English and the French commanders.

Adolf Hitler on the left during WWI

The WW1 will always be etched on the collective memories of humankind as the most pointless war in history. The response of all commanders to the stalemate was idiotic and uninsightful at best. Instead of desisting from their murderous advances against well entrenched machine guns, the same baleful tactics were employed on a daily basis as if their opponents would exhaust their ammunition. The Battle of the Somme epitomises that futility of that method of attack. Moreover it exposes the banal lack of intellect and imagination on the part of the Commanders.

What must it have felt like for a soldier “going over the top” knowing full well that the chances of being killed were no more than even?

German machine gun post

I shudder to think.

Unfortunately the world is still plagued with the same insane mentality, except that these people – and not only men – are the foot soldiers of extremist philosophies where human life counts for naught. Foremost amongst such organisations are the murderous ISIS and Boko Haram.

If ever there was a morally justifiable war to be waged, surely it is against these forces of darkness and death?

I think so.

War is never an answer and it never produces winners. I feel very fortunate that I have never experienced a war directly!

I agree. War seldom resolves problems. Of course sometimes one has to go to war. As I suggest in the blog, maybe attacking ISIS and Boko Haram is one such situation