The ultimate litmus test of experimental drugs and technology is the human acting as a surrogate guinea pig. This is the gold standard. The recent fatality of a driver using an experimental Automated Driving System called Autopilot has brought this issue to the forefront of what constitutes ethical testing once again.

Should testing standards ever be relaxed in order to fast track development such as occurred with this self-driving Tesla and what, if any, controls need to be implemented to ensure that humans do not perforce become the 21st century guinea pigs.

Main picture: The remains of the Tesla S which is at the centre of the self-driving vehicle controversy

In 21st century argot, the sanctity of human life might be the most hackneyed cliché through overuse but this is a relatively recent concept.

Historically slaves and the underclass were always involuntarily used as human guinea pigs. A blasé almost uncritical acceptance of this reality pervaded the world in ancient times.

Tesla Motors Inc. Model S car equipped with Autopilot in Palo Alto, California, U.S., on Wednesday, Oct. 14, 2015. Tesla Motors Inc. will begin rolling out the first version of its highly anticipated “autopilot” features to owners of its all-electric Model S sedan Thursday. Autopilot is a step toward the vision of autonomous or self-driving cars, and includes features like automatic lane changing and the ability of the Model S to parallel park for you. Photographer: David Paul Morris/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Jenner: The father of vaccinations

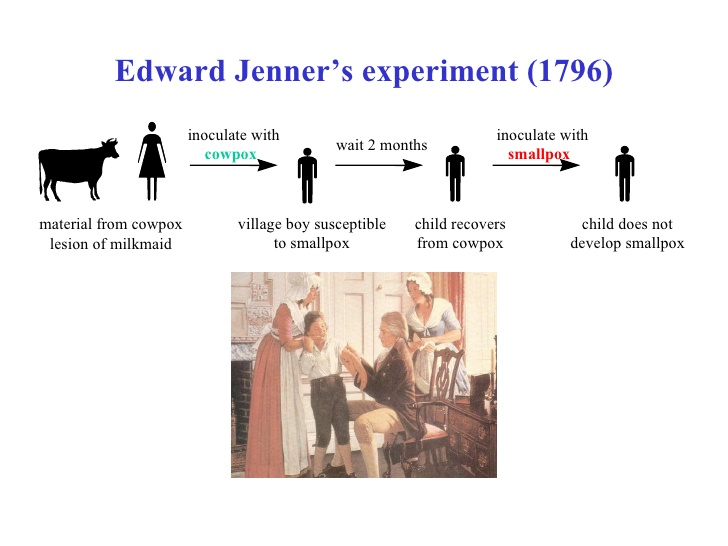

The first such incident in which the morality of human experimentation was raised is that of Edward Jenner and smallpox.

The starring villain in this experiment in vaccinations was Edward Jenner, an English physician and scientist who was the pioneer of the smallpox vaccine, the world’s first vaccine. He is often called “the father of immunology“, and his work is said to have “saved more lives than the work of any other human”.

Writing of this, Voltaire noted that at this time 60% of the population caught smallpox and 20% of the population died of it.

François-Marie Arouet known by his nom de plume Voltaire was a French Enlightenment writer

Edward Jenner was by no means the first person to realise that persons who contracted cowpox naturally such as milk maids were immune from dying from smallpox. In fact by 1768, an English physician John Fewster had realized that prior infection with cowpox rendered a person immune to smallpox. In the years following 1770, at least five investigators in England and Germany successfully tested a cowpox vaccine in humans against smallpox. For example, Dorset farmer Benjamin Jesty successfully vaccinated and presumably induced immunity with cowpox in his wife and two children during a smallpox epidemic in 1774, but it was not until Jenner’s work some 20 years later that the procedure became widely understood. Indeed, Jenner may have been aware of Jesty’s procedures and success.

Engraving of Edward Jenner, the British physician

It is what Jenner subsequently did that proved conclusively that cowpox could immunise against smallpox. How he did it is less well-known.

Jenner selected his “victim.” It was James Phipps, the eight year old son of Jenner’s gardener. Whether James’ father was aware of the possible ramifications of the test or was even afforded an opportunity to object to the procedure is unknown.

What we do know is that on the 14th May 1796 Jenner scraped some pus from cowpox blisters on the hands of his milk maid, Sarah Nelmes. The final actor in this episode was a cow called Blossom which was suffering from cowpox.

On that fateful day, Jenner inoculated Phipps in both arms. Phipps developed a fever and some uneasiness but not full-blown infection.

Edward Jenner administering the first smallpox vaccination in 1796. Painting by Ernst Board

The standard treatment before the use of cowpox was a substance called variolous which was more virulent than cowpox but less harmful than smallpox. The problem was that the treatment by variolous could have serious repercussions.

In true scientific manner, Jenner injected Phipps with variolous material subsequent to his inoculation with cowpox. No disease ensued.

Donald Hopkins has written, “Jenner’s unique contribution was not that he inoculated a few persons with cowpox, but that he then proved [by subsequent challenges] that they were immune to smallpox. Moreover, he demonstrated that the protective cowpox pus could be effectively inoculated from person to person, not just directly from cattle. Jenner successfully tested his hypothesis on 23 additional subjects.

Subsequently the term vaccination was coined. This word is derived from the word vacca, Latin for cow.

Despite being a resounding success, the ethics of experimentation on humans now came to the forefront of the testing of medications

Human Plutonium Experiments

On the 10th April 1945 before the first atomic bombs were dropped on Japan, the world’s first micrograms of plutonium produced at the Manhattan Project secret site “W” in Richland, Wash., were sent to Los Alamos for tests of a new atom bomb.

Scientists and workmen rig the world’s first atomic bomb to raise it up into a 100-foot tower at the Trinity bomb test site in the desert near Alamagordo, N.M. in July 1945.

That wasn’t their only destination. Plutonium also went to several hospitals within the Project. The first human plutonium injection occurred on April 10, 1945. The human subject called “Hp 12” was Ebb Cade, a 55-year-old African-American cement mixer who landed in the Manhattan Project Army Hospital in Oak Ridge, Tenn., after an automobile accident that left him with several broken bones.

Researchers hoped to harvest bone samples, liver and other organs after the man died. Suspicious of his “treatment,” he ran away from the hospital, expiring eight years later of heart failure. But he was only the first of hundreds of thousands of people subjected to voluntary and involuntary medical radiation experiments in the four decades that followed.

Trinity test

Cade’s injection marked the start of a troubling phase in American history, during which individual rights were sacrificed for the supposed good of a nuclear nation.

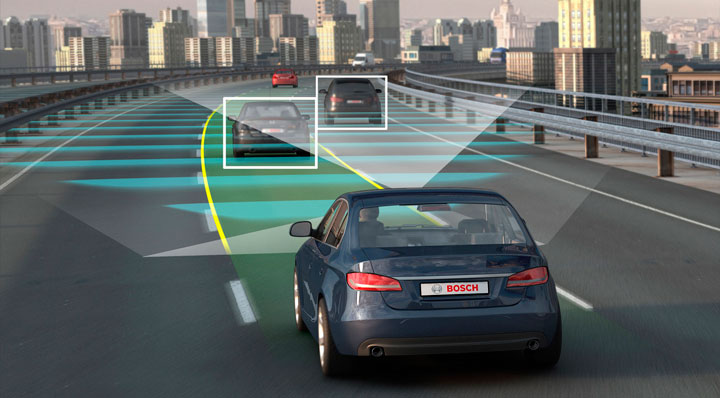

Self-driving vehicles

The latest foray into human testing is by Tesla.

The world’s first self-driving fatality has been confirmed. The accident occurred when “the driver of a Tesla S sports car operating the vehicle’s Autopilot automated driving system died after a collision with a truck in Florida”.

Preliminary reports indicate that the crash occurred when a tractor-trailer rig made a left turn in front of the Tesla at an intersection of a divided highway where there was no traffic light.

Tesla acknowledged the accident and noted that neither the driver nor the autopilot noticed the trailer “which was perpendicular to the Model S, against the brightly lit sky”.

This is the first death in over 130 million miles of Autopilot operation according to Tesla. In spite of the accepted norm of one fatality for every 92 million miles driven, this crash will indubitably reopen the debate whether drivers should be allowed to hand over control to a computer while driving. The first indications are that the driver could have been watching a DVD when the accident occurred.

Volvo’s concept car

This fatality will never be an existential threat to self-driving vehicles but it calls into question the light regulator touch which has been applied by the Transportation authorities. This policy has been enforced so as not to hamstring innovation.

The greatest threat to self-driving vehicles is not that of the fatalities per se but the fact that litigation after each crash might make the cost of self-driving prohibitively expensive.

What is more concerning to certain NGOs is that unlike regular motor manufacturers, experimental unproven technology has been unleashed onto an unsuspecting driving public on normal roads.

Quo Vadis?

The risks associated with new treatments and technology will always be greeted with distrust, suspicion and outright hostility by certain segments of society especially the congenitally risk-averse.

In the headlong rush to adopt new ways of doing things many have voiced similar concerns.

My viewpoint is more nuanced.

In the case of patients in the throes of death due to some dread disease, these patients should be entitled to subject themselves to any untested treatment subject to the caveat of informed consent. Even if there is only a faint glimmer of hope, even an unsuccessful experiment is useful in that it will eliminate one option.

Personally I would allow the use of experimental treatment even on patients who are gravely but not terminally ill. Here the defining factor should be more than the confidence exuded by a researcher but at least some preliminary animal tests. Again the patient’s consent is non-negotiable.

In general I concur with the transport regulators’ opinion that applying alight regulatory touch is conducive to progress. If the world insists on a 100% foolproof test, what is the point? Will not innovation, discovery and invention become so arduous and demanding that they will be stalled.

Balance is required. But what is balance? Is one fatality in a Tesla on Autopilot one death too many?

Clearly for many it is.

Fortunately the rate of death whilst using an unproved technology was far below that of vehicles under human control. Even so, will such an argument staunch the flow of invective against self-driving cars?

Never!

Whilst I too mourn the loss of life, it was neither gratuitous nor unexpected.

Vehicles crash.

People die.

Sad but true.

In no way does this incident equate to the testing of Plutonium on unknowing patients. Only under the threat of a possible nuclear Armageddon or anti-Communist hysteria could this perhaps, just maybe, be justified. Even then I do not concur with what was done. Far from it. It was inexcusable in a democracy and a vibrant one at that.

Even Jenner’s case is excusable. It was entirely plausible in that case that cowpox would inoculate against smallpox as there was anecdotal evidence to that effect.

The concerns raised in the Tesla case must not be allowed to derail technological advance.

Only the 21st century Luddites with their anti-technological predilections will be the victors.

Sources

Edward Jenner: Wikipedia

Plutonium tests: Article by Kate Brown in Time Magazine

Self-driving vehicles: PBS