Lewis Michell first came to prominence as the General Manager of Standard Bank in Port Elizabeth. His tenure at the bank would result in a friendship with Cecil John Rhodes, the arch imperialist. Before his death in 1928, Michell had completed his autobiography. Despite never being published, portions of it have been used by other authors, the latest being the book on Rhodes by Richard Steyn entitled Rhodes and his Banker.

I am indebted to Jon Inggs for introducing me to this manuscript. The chapter on Port Elizabeth was especially interesting as Michell eloquently portrays not only the Town itself but also provides insightful comments on some prominent residents of Port Elizabeth.

Jon Inggs has used the AI program NoteBookLM to generate this blog and I have not amended it in anyway at all, even insignificantly. At the end of the blog I have included a copy of Michell’s original chapter on his assessment of the residents and the town itself. Likewise I have not made any amendments to the original. The reason why I included both the original and the AI version in this blog was to provide a way to assess the accuracy, fluency and readability of the AI version. On all counts I am impressed with AI’s ability to summarise the data under appropriate headings. On the negative side I found the AI version to be slightly rigid, even sterile, with little emotion, more akin to a text book than story. Perhaps that is how it should produce a formal assessment but I am not necessarily convince. Judge for yourself.

A Banker’s Passage: The Making of an Expatriate in 19th-Century South Africa

Introduction: A Young Man on the Threshold

In the summer of 1863, just days shy of his twenty-first birthday, a young Lewis Michell stood on the threshold of a life he could scarcely imagine. As a newly appointed probationer for the London and South African Bank, his immediate world was the bustling heart of the British Empire, but his future lay across an ocean, on the developing shores of a distant colony. His personal story, captured in his own words, is more than a memoir of a banking career; it is a vivid chronicle of the life-altering journeys undertaken by a generation of young men who left the certainties of Victorian England to forge new lives within the vast machinery of colonial enterprise. His passage was not merely geographical but transformational, marking the end of his English youth and the beginning of his identity as a South African.

1. The London Prelude: Forging a Character (1863-1864)

Michell’s six months in London were far more than a simple interlude before his colonial posting. This period proved to be a profoundly formative experience, a time in which he established the personal interests, intellectual curiosity, and social connections that would shape his character for decades to come. Yet the true forging of his character took place not in the ledgers of the bank, but in the vibrant cultural crucible of London itself, which provided him with a rich inner world that would sustain him long after he left England’s shores.

1.1. A Probationer’s Life in the City

Michell’s professional induction at the London and South African Bank was, by his own account, remarkably casual. With a salary of £100 a year, he and his fellow probationers endured a training he dismissed as “slack and ineffective.” The work was light enough to leave ample time for relaxation, which for Michell and his Scottish colleague, Sandy Hay, often consisted of “fencing bouts in a back room.” This leisurely pace stood in stark contrast to the momentous life change that awaited him.

1.2. An Education Beyond the Bank

In the libraries, theaters, and lecture halls of the capital, Michell found his true education. His quiet lodgings in Myddleton Square suited his temperament as a “great reader,” content in his own company. This period was defined by a deep immersion in the arts and ideas of the day, revealing an intellectual and artistic inclination that would become a lifelong trait.

- Literary and Intellectual Pursuits: His most significant influence came from his friends, the Courtney brothers. In their quarters in Great Ormond Street, Michell found a welcoming intellectual circle, access to a good library, and the opportunity to play chess and converse with men who would go on to distinguished careers in “Church and State.”

- Theatrical and Musical World: Michell took full advantage of London’s vibrant performing arts scene. He recalled a breathtaking array of talent, hearing singers then in their prime such as Sims Reeves, Santley, Adelina and Carlotta Patti, Trebelli, and Parepa. Among actors, it was the comedian Buckstone who left the most indelible mark. Reflecting on his inimitable performances, Michell wrote with deep appreciation, “I know I shall never look upon his like again.”

- A Masterclass in Oratory: A particularly memorable evening was spent at Exeter Hall, listening to the great American orator Henry Ward Beecher speak on the U.S. Civil War. Though Michell and his friend sided with the “picturesque Southerners,” they were completely captivated by Beecher’s commanding presence. Michell recounted the effect of his “dominant personality,” observing how the orator “played upon us as a master plays on a musical instrument and ere long we were all as children in his hands.”

1.3. Farewell to England

As his departure neared, Michell was formally summoned before the bank’s Board of Directors, where he felt “rather abashed at the flow of advice given by the Directors in seriatim.” Amidst the formal instructions, one small gesture of humanity stood out. As Michell was leaving, a director named Mr. Adolph Rosenthal leaned in and whispered a piece of practical advice: “And when you feel ill on board take a nip of brandy.” This “entirely human utterance,” as Michell called it, resonated deeply with the young man, cutting through the formality of the occasion with a moment of simple kindness.

With his farewells made, Michell prepared to leave London behind for the arduous sea voyage that lay ahead.

2. The Voyage to the Cape: A Passage Between Worlds (February 1864)

Long before the age of luxurious liners, the nineteenth-century sea voyage was a fundamental rite of passage for the expatriate. It was a period of stark separation—a physical and psychological gulf that divided the old world from the new. For Michell, the journey aboard the “Briton” was an introduction to a different pace of life and a final, irreversible step away from the world he had always known.

2.1. Life Aboard the “Briton”

The 38-day journey from Plymouth to South Africa began on February 6, 1864, in “exceptionally wild” weather. The vessel was the “Briton,” an 800-ton sailing ship equipped with an auxiliary screw. Life on board was a world away from modern sea travel; the principal figure, Michell noted, “was not Captain Boxer but his wife.” Entertainment was limited to a noisy “bull board,” the food was “plain,” and the only drink on offer was a “peculiarly indifferent one known as Carston’s Bristol Ale.” Despite the spartan conditions, a great sense of pride was felt by all when the ship arrived four days ahead of its 42-day contract time, an achievement marked by a congratulatory cannon shot from the company agent’s home at Sea Point.

2.2. A Vision of Maritime Grace

The voyage was largely uneventful, but one moment of breathtaking beauty stood out in Michell’s memory. The ship encountered three China Tea Clippers, homeward bound and sailing under a full and enormous cloud of canvas. The spectacle of these magnificent vessels running with a fair wind inspired a sense of profound awe. It was, he reflected, a sight of pure maritime grace for which there is “no finer sight on sea or land.“

His long voyage successfully completed, Michell was ready to take his first steps on South African soil.

3. First Impressions: The Gateway to a New Continent

As the seat of government and the primary port of entry for the colony, Cape Town was the initial cultural and professional touchstone for newcomers like Lewis Michell. It was here that he first encountered the landscape, the people, and the nascent infrastructure of the world that would become his home.

3.1. Arrival in Cape Town

Like countless arrivals before and since, Michell’s first act ashore was an attempt to ascend the iconic Table Mountain, an effort he dryly recorded as a “miserable failure.” His formal duties began soon after with a call to present a note of introduction to the Governor, Sir Philip Wodehouse, and his wife, who received him graciously.

3.2. A Glimpse of a Developing Land

Michell was immediately put to work. His first assignment was to deliver a consignment of specie to the branch in Wellington, a 40-mile journey away. This short trip carried immense significance, as Michell noted that in making it, he had “traversed in a few hours the whole railway system of South Africa.” The fledgling state of the colony’s infrastructure was powerfully illustrated by a formal notice he preserved from a local paper, which announced the opening of the suburban line to Wynberg just after his arrival. As a curiosity, he recorded its full text:

THE WYNBERG RAILWAY

Notice is hereby given that the Railway between the Salt River Junction and Wynberg, Will be OPENED FOR PUBLIC TRAFFIC ON MONDAY NEXT THE 2nd MAY.

Trains will run between the Salt River Junction and Wynberg in connection with trains on the Cape Town and Wellington Railway as follows:

Leaving Cape Town at 7.00. and 10.50 a.m. and 5.50 p.m., and Wynberg at 8.10 and 12.50 p.m. and 4.40 p.m.

Fares from Cape Town to any Station on the Wynberg Railway, One shilling each, without distinction of Class, and the like fare from any Station on the Wynberg Railway to Cape Town.

The trains will call at the following intermediate stations on the Wynberg Railway, viz: Mowbray, Rondebosch, Newlands and Claremont.

By Order of the Board of Directors JOHN STEIN Chairman.

CAPE TOWN, 28th April 1864.

3.3. Observing a New Culture

During his brief stay, Michell observed the local culture of Cape Town, paying particular attention to the “picturesque” Malay community. He noted their distinctive immense hats and the wooden sandals they wore, held by a nail between the toes. A fascinating insight into the meeting of tradition and modernity came from an ecclesiastical ruling regarding the new railway: its use by the community was deemed permissible because railways “were not wheeled vehicles within the meaning of the Koran, as the wheels were not of wood.” Beyond such curiosities, Michell was struck by a quality he believed remained true throughout his time in the country: they were “wonderfully abstemious as well as industrious,” setting a fine example.

His short orientation in Cape Town complete, Michell soon proceeded to his ultimate destination: the rough-and-ready port of Algoa Bay.

4. Port Elizabeth: Life in a Frontier Town

Port Elizabeth, as L. Michell first encountered it, was a place of stark contrasts. On the one hand, it was a frontier town with “archaic” facilities and primitive conditions. On the other, it was a “cheery spot” animated by a palpable “progressive tone” and a restless, optimistic drive for improvement. This duality would define his early years in the colony.

4.1. An Unattractive Welcome

Michell’s arrival was anything but gentle. He landed in a surf boat, navigating what he perceived as “appalling breakers” under the masterly guidance of a Greek coxswain named Messina. His initial assessment of the place was blunt: it was “singularly unattractive.” It is a testament to the town’s hidden charms and the life he would build there that he added the poignant reflection that he, bound to stay for five years, would ultimately remain for twenty-one and “leave it with regret.”

4.2. Finding a Foothold

Despite the rough welcome, Michell quickly established himself. He found his footing through a stroke of good fortune, securing lodging as a boarder with the Rev. H. H. Johnson. He also immediately connected with a community of fellow chess players, which provided the intellectual and social stimulation crucial for a young man far from home.

4.3. A Town of Deficiencies and Friendliness

Michell’s account paints a vivid picture of a town grappling with its limitations while cultivating a rich social fabric. Though lacking in basic amenities, its open and hospitable character made it a welcoming place for a newcomer.

| Deficiencies | Strengths |

| Archaic landing facilities | A “cheery spot” with a progressive tone |

| Wind-swept, sandy streets | Much informal hospitality and friendliness |

| Scarce drinking water | A fair Library |

| No telegraphic facilities | A Race Course and Cricket Ground |

| Not a single mile of railway | Gradations of society were not very rigid |

The residents did not passively accept these deficiencies; they actively worked to build a vibrant community, laying the foundations for the town’s future.

5. Building a Community, Crafting a Life

In a colonial outpost like Port Elizabeth, social institutions were the lifeblood of the expatriate community. Clubs, societies, and shared pastimes were essential in creating a sense of civilization, belonging, and recreation, transforming a rugged frontier town into a home. Michell was not just an observer of this process; he was an active participant in it.

5.1. The Birth of Social Hubs

Michell witnessed and took part in the establishment of key community institutions that provided structure and entertainment to local life.

- The P.E. Club (1866): Michell was an original member of the Port Elizabeth Club, founded in 1866. He saw its creation as a “power for good,” providing a respectable venue where young men could play billiards and cards as an alternative to “public houses and worse.” Writing many decades later, he noted he was the last surviving original member of this influential social hub.

- The River Club & Dramatic Society: The community’s social life expanded with the founding of the River Club for leisure activities like fishing and yachting, and an Amateur Dramatic Society. The latter not only provided great enjoyment for its members but also netted a “fair annual profit for local charities.”

5.2. Personal Pursuits and Adventures

Beyond organised clubs, Michell crafted a life rich with personal interests and memorable adventures that connected him deeply to his new environment.

- Sports & Scribbling: He was an active sportsman, playing for the local cricket club and as a member of the “first 15 at football.” He also indulged his intellectual habit of “scribbling,” a harmless vice that found a significant outlet in 1869 when he wrote a letter to the London Times arguing against the withdrawal of Imperial troops from South Africa.

- Walking Tours: One of his greatest pleasures was the occasional walking tour. He vividly recalled one Easter trip that included a night in a reputedly haunted house near Kragga Kamma, sleeping on the beach at St. Francis Bay, and a stay at the cherished “honeymoon cottage” of the district, Mrs. Cadle’s Hostelry. His reflection on the hostess powerfully illustrates the nature of colonial hospitality: “no warmer heart ever beat in the breast of a wayside hostess than in the ample figure of Mrs Cadle.”

His personal life was woven into the fabric of a town populated by a fascinating cast of characters who left their own indelible marks on his memory.

6. Portraits of a Colonial Society

The vitality of Port Elizabeth in the latter half of the nineteenth century is best understood through the unique individuals who gave the town its character. Michell’s recollections serve as a gallery of vivid portraits, capturing the dreamers, doers, and eccentrics who animated this burgeoning colonial society.

6.1. The Visionaries and The Doers

Michell’s account highlights several figures whose ambition and vision were instrumental in shaping the town and the region.

- James Somers Kirkwood: Michell saw Kirkwood as a “dreamer devout” with visions as grand as those of Cecil Rhodes but without the latter’s practical business instincts. Kirkwood’s ambitious plans for irrigating the Sundays River Valley eventually came to fruition long after his death, a testament to a mind ahead of its time.

- Wm. Fleming: A versatile genius, Fleming was a man whom nature intended to be a master of marine architecture but whom “unkind fate” made into a commercial magnate. He was the first to exploit the sole fishery on the Agulhas Bank and concluded his career as the town’s mayor.

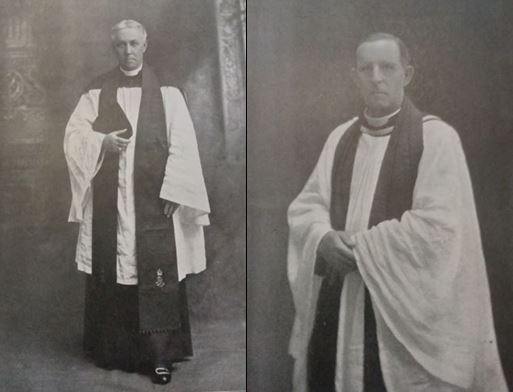

- Rev. A. Theodore Wirgman: The arrival of this “irrepressibly active high churchman” in 1875 revolutionized local church affairs. Wirgman’s “volcanic energy” and his controversial introduction of vestments and Gregorian music profoundly disturbed the “old sleepy condition of affairs.” Despite fierce opposition, Michell became his “only whole-hearted supporter,” admiring the man’s tireless efforts.

6.2. Notable Characters of “The Bay”Beyond the town’s leaders, Michell fondly remembered a host of other colorful personalities who populated his world.

- He described the inseparable bachelor friends Hugh Cameron Ross and Matthew Jennings, recounting a humorous anecdote of a buffalo hunt in the Addo Bush where the portly Jennings “climbed a tree, looking so Pickwickian” that their uproarious laughter scared the animal away.

- He recalled two mariners, Captain Frank Skead (“North Pole Skead”) and B. Ladds (“South Pole Ladds”). Skead earned his nickname from an expedition to find Sir John Franklin, while Ladds was an extremely cautious captain who, when bound for Table Bay, would “steer as if his destination was Australia or the Antarctic.”

- He chronicled the arrival of Sir George Farrar, who first appeared as an unknown but triumphant sportsman at a local club. Farrar would later make his fortune on the gold fields and become a leading political figure in the Transvaal, a remarkable trajectory for the young man who first made his name in Port Elizabeth.

These individuals shaped the social landscape of the town, just as larger forces of nature and progress shaped its physical on

7. The Tides of Change: Development, Rivalry, and Nature’s Power

Life in a colonial port was defined by a constant tension between the ambitious drive for development and the formidable, often unpredictable, challenges posed by natural forces and regional competition. Port Elizabeth’s story during Michell’s tenure was one of battling the elements, vying with its neighbours, and witnessing nature’s awesome power.

7.1. The Saga of the Jetty

The town’s struggle to develop its harbour serves as a powerful metaphor for its broader challenges. The first major wooden jetty, designed by an architect rather than a marine engineer, proved to be a disaster. The designer completely overlooked the issue of sand travel along the coast, and the structure acted as a dam, causing the port to rapidly silt up. The government eventually intervened, bringing in the eminent expert Sir John Coode, whose recommendations for an open-work structure that allowed sand to pass through ultimately saved the port.

7.2. A Rivalry of Ports

The spirit of competition among the Cape’s ports was fierce. Michell describes an “unholy alliance” that formed between Port Elizabeth, East London, and Port Alfred to protest against the rising ambition of Durban in Natal. This parochialism, rooted in the belief that one port could only thrive at the expense of another, drove much of the era’s regional politics before a more modern understanding took hold that “healthy inter-port rivalry is all to the good.”

7.3. Encounters with the Sublime and the Dangerous

Life was punctuated by extraordinary natural events and dangerous encounters that reminded residents of their vulnerability.

- The Krakatoa Eruption (1883): The effects of the cataclysmic eruption were felt worldwide. In Port Elizabeth, a jetty watchman reported three high tides in a single night. He was promptly “suspended for being drunk while on duty,” but was reinstated a few days later when cable reports confirmed the phenomenon had been observed across the globe. In the following months, strange fish appeared off the coast, beaches were littered with “incredible quantities” of pumice stone, and the sunsets were obscured by a “strange fantastic mist.”

- Perils of the Sea and Bush: The community’s enjoyment of sea bathing received a “rude shock” after a man was killed by a shark right at the jetty steps. This danger was later contrasted with a comical incident where a friend, having fallen asleep and slipped into a tidal river, had to be convinced by his rescuers that he had not been “sharked.” Michell himself had a “nearer shave” when he and a friend on horseback were chased by two “vicious elephants” in the bush, barely escaping with their lives.

These vivid memories of progress, conflict, and survival form the core of his reflections on his transformative early years in South Africa.

Conclusion: Reflections from a New World

Sir L. Michell’s personal account is a chronicle of profound transformation. It traces his journey from a young, untested English banking clerk into a foundational member of a new and burgeoning colonial society. But its significance extends beyond the personal. Through his sharp observations and vivid anecdotes, he captures the very essence of that society—its primitive struggles and progressive ambitions, its parochial rivalries and generous hospitality, its human dramas and its encounters with the raw power of nature. His story is that of a man and a community growing up together. Recalling his unpromising arrival in the “singularly unattractive” Port Elizabeth—a place he was indentured to for five years but would ultimately remain in PE for twenty-one and leave with regret—he offered a poignant and fitting reflection on the unpredictable course of a life spent in a new world:

“We never know what Fortune has in store for us and it would often be a duller world if we did.”

Addendums

1. Brief biography of Lewis Michel

2. Sunnyside House, Bird Street

Standard Bank first commenced business in Port Elizabeth in January 1863, purchasing Sunnyside House in Bird Street a decade later on the 25th September 1873 from Helen Deare for £3300 which was the same price that she had paid Von Ronn for it in 1864. Its purpose was to serve as the residence of the Bank’s most senior manager. In this role it would be occupied by the Bank’s General Managers from 1873 to 1885 and thereafter by the Port Elizabeth Branch Manager until 1938. Presumably 1885 is when the Bank’s Head office was relocated from Port Elizabeth to Cape Town.

Source: Looking Back, Volume 23 No. 1, 1983

Original manuscript by Michell about Port Elizabeth

3. Michell’s recounts his life in P.E.

This extract from Michell, Sir L, Sixty years in and out of South Africa (unpublished autobiography) are exactly the same chapters used by Jon Inggs in his test of AI commencing from page 48

-48-

Chapter IV.

LONDON AND SOUTH AFRICA : 1863-1864.

On the first day of August 1863, a few days before my 21st birthday, I entered the service of the London and South African Bank at 10, King William Street, adjoining Ridgways, the Tea Merchants. There for six months I made a pretence of working with two other probationers, one of them with the very English name of Hampden Hume, the other a typical Scot known as Sandy Hay. The salary was £100 a year but I paid my way on it and even remitted something to my mother. Our training was slack and ineffective and I picked up little banking practice that I had not already acquired at Penzance.

The Work, such as it was, left time for odd hours of relaxation which so far as Hay and I were concerned, consisted of fencing bouts in a back room. Occasionally the delivery or collection of Bills of Exchange took me to the offices of the Bill Brokers, Hichens and Harrison and Foster and Braithwaite, both firms, I believe, are still in existence.

My modest lodgings were quiet ones at No.18 Myddleton Square, Clerkenwell. My landladies were two maiden ladies no longer young who, I think, had seen, like the Square,better days. They furnished me together with a latch key, a few appropriate remarks on the advantage of sobriety and early hours and they made an effort to teach me how to coax the sitting room clock to go, but that ancient time-piece had views of its own and refused to regard my overtures as serious. But my hostesses were entirely to my liking. They were like Charles the Second’s model courtier, never in the way and never out of the way, and when we finally parted it was with expressions of mutual esteem. Fortunately for their peace of mind and probably more fortunately for my own, I was a great reader and quite content with my own company. Moreover

-49-

I had two friends, to whom I still feel that I owe much, sons of my late “Baas” Mr. Courtney of Penzance. One of them,- Leonard, a Barrister, had made his mark at Oxford and was now on the staff of the “Times” the other, William Brideaux, was a clerk in the office of the Ecclesiastical Commissioners.

Their quiet quarters were in Bowes Place, Great Ormond Street, and I was made free of them to my great advantage. There I played chess, had the benefit of a good library and met many men who had since done well in Church and State. Both my friends have since passed away. But notwithstanding the “want of pence,” which vexes private as well as public men, I managed to see something of the sights and sounds of London, and I once saw at Opera or Theatre a then very handsome pair of sisters idolized by the people, the Princess of Wales and Princess Dagmar. Their brother, Prince George, was with them.

For them, as for all of us, much water has passed under the bridges since that night. Amongst the singers then in their prime I heard Sims Reeves, Santley, Adelina and Carlotta Betti, Bettini, Bossi, Trebelli, Parepa and many others. Among conductors I recall Julien, Benedict, Manns and Arditi; among organists Goss and Coward; and among other musicians Sir Charles Halle, Arabella Goddard, Dannreuther, Sivori, Lotto, Webb and Ries. Of actors I saw but few, but among those few were Phelps, Charles Kean, Fechter, Sothern and Buckstone. The last named has left, I think, no successor, For in comedy, as distinguished from farce, he was without a rival. Even now in visions of the past, I often recall his inimitable characterisation of parts he had made his own, especially in Sheridan’s plays. I have long since lost my love of the theatre, indeed the theatre seemed to have been brushed aside by the Music Hall and the Music Hall is now being jostled by the Cinema. But I still laugh sometimes when I remember Buckstone and I know I shall never look upon his like again. May the earth lie lightly on the graves of all who provide, as he did, honest amusement, without taint of vice or vulgarity, for the ever growing masses who

-50-

gravitate towards city life. Public entertainers of Buckstone’s type are as necessary and useful as the pulpit or the press,and deserve more from us than they receive. Speaking of thepulpit reminds me that during my six months in London, I cannot recall the names of any preachers who had the gift of persuasive oratory, but perhaps my recollection of Hedgeland was too recent to admit of my doing justice to the London “high and dry” Divines.

But I did hear one indubitably great oratorin Henry Ward Beecher who spoke one night in Exeter Hall on the vexed question of the day, the right of the Southern States to secede from the North on the slavery issue. Leonard Courtney, I think, was on Beecher’s side; his brother and I were for the picturesque Southerners. Exeter Hall has long since passed away, but my memory still holds the smallest details of that evening, the densely crowded Hall, the mixed sympathies of the audience and its gradual conquest by the dominant personality of the great orator, whose voice, now flute-like, now peeling in organ tones, gradually prevailed over prejudice and passion. He played upon us as a master plays on a musical instrument and ere long we were all as children in his hands. It was a memorable night and has had no successor of equal intensity.

As indicating the survival at this time of old customs that have since passed away, I find that I wrote to Mrs. Hodge that on 5th November 1863 “Guy Fawkes, the rope and President Lincoln had been duly burnt in effigy”.

Towards the close of 1863, it was intimated to Hay and myself that we should be required to proceed to our destination early in the new year. One memorable day, therefore, I was called before the Board to receive their farewell instructions. Perhaps I felt rather abashed at the flow of advice given by the Directors in seriatim. It was doubtless good but there may have been too much of it. At all events this was on the mind of one member of that August

-Page 51-

body, for on my having “leave to depart” and in a great hurry to do so, he whispered as I shook hands “And when you feel ill on board take a nip of brandy”. This entirely human utterance drove away my nervousness and I followed his advice, even if I forgot that of all the others. The speaker was that fine old German gentleman Mr. Adolph Rosenthal, from whose son Harry, also now dead, I received much kindness both in Port Elizabeth and London.

I embarked on the U.S.S.Co’s “Briton” at Plymouth on 6th February 1864. The weather was exceptionally wild and I gladly draw a veil over our first week at sea. The “Briton” was a roomy sailing ship with an auxiliary screw and her tonnage was about 800. The contract time was 42 days and we made the passage in 38, calling nowhere and indeed never seeing land until Table Mountain appeared on the horizon. The day of the luxurious liner had not arrived There were few passengers and the principal figure on board was not Captain Boxer but his wife. There were no deck games barring a noisy “bull board”, the food was plain and the only liquor a peculiarly indifferent one known as Carston’s Bristol Ale. I do not remember passing any other steamer, but on one occasion we saw a sight which for picturesqueness beat any steamer that ever was launched for we met three China Tea Clippers homeward bound, with a fair wind and an enormous cloud of canvas, than which there is no finer sight on sea or land.

We were very proud of our achievement in arriving three or four days under contract time, especially when a congratulatory gun was fired at Sea Point from the residence of that cheery veteran, Captain Harrison, the Company Agent. I was glad to be on shore again and to sleep in a real bed again. The lodging house was in Roeland Street but I have no record of the landlady’s name and even the house is unrecognizable. Of course, Hay and I at once started off, like all newcomers, to ascend Table Mountain and we made a

-52-

miserable failure of it. The next morning I called on the Governor, Sir Philip Wodehouse, to present a note of introduction to Lady Wodehouse, from Mrs. Michell Hodge and Their Excellencies were very gracious. He sailed a few years later to occupy the Governorship of Bombay, but his wife died before he left these shores and lies in a somewhat neglected grave in Rondebosch Churchyard. Sir Philip was the first Governor of the Cape I met; thence onward I knew a long succession of them until the line ended with Sir Walter Hely-Hutchinson in 1909.

Of course I called on the Cape Town Manager of the Bank, Mr. C. M. More, a fine upstanding figure of a man and I believe an excellent Banker. His office in Adderley Street is now a tobacconist’s shop. He was good enough to “inspan” me at once by entrusting me with a consignment of specie for the Wellington Branch 40 miles away. I returned the same day having traversed in a few hours the whole railway system of South Africa, which now amounts to over 15,000 miles. In those early days the suburban line to Wynberg was then only partly constructed, but was approaching completion, and was officially opened the month after my arrival. As a curiosity, I subjoin the following notice that appeared in the “S.A. Advertiser and Mail” of 30th April 1864:-

THE WYNBERG RAILWAY

Notice is hereby given that the Railway between the Salt River Junction and Wynberg,

Will be OPENED FOR PUBLIC TRAFFIC ON MONDAY NEXT THE 2nd MAY.

Trains will run between the Salt River Junction and Wynberg in connection with trains on the Cape Town and Wellington Railway as follows:

Leaving Cape Town at 7.00. and 10.50 a.m. and 5.50 p.m., and Wynberg at 8.10 and 12.50 p.m.and 4.40 p.m.

Fares from Cape Town to any Station on the Wynberg Railway, One shilling each, without distinction of Class, and the like fare from any Station on the Wynberg Railway to Cape Town.

The trains will call at the following intermediate stations on the Wynberg Railway, viz: Mowbray, Rondebosch, Newlands and Claremont.

By Order of the Board of Directors

JOHN STEIN Chairman.

CAPE TOWN, 28th April 1864.

-Page 53-

The Cape Town I saw in 1864 has changed a great deal since I arrived. Stoeps then disfigured nearly all the principal thoroughfares including Adderley Street. The Malays were the only picturesque people to be seen. They were almost the sole drivers and the immense hats they wore are now altogether in disuse. Walking they used wooden sandals with a nail between the great toe and its neighbour. They carried their dead to their own cemeteries however distant, until railways came and with them a declaration by their great ecclesiastical authority that their use was permissible because they were not wheeled vehicles within the meaning of the Koran, as the wheels were not of wood. There is one point about our South African Malays which at once struck me and which even now remains.

They are wonderfully abstemious as well as industrious in both which respects they give a good example to many white people. It is true now as on the day I landed.

We were only a few days in Table Bay before proceeding to our final destination, Algoa Bay, then the terminus for the mail boats. Beyond this, small coasting steamers were used. I can vividly remember our landing in a surf boat amid what appeared appalling breakers. Our coxswain, a Greek named Messina, steered in a masterly manner and though today in a very superior position as a boat owner, he is still in harness and about the only man at Port Elizabeth who remains of all those whose acquaintance I made on my arrival. The place was singularly unattractive to a newcomer. I was bound by my indenture to remain in the Bank for five years and I little thought I should remain at the Port for 21 years and leave it with regret.

We never know what Fortune has in store for us and it would often be a duller world if we did. The Bank was in its infancy, its Manager, Miller, a rough but competent representative. I think the first acquaintance I made was the Rev. W. Pickering, Colonial Chaplain and Rector of St. Mary’s; and he introduced me to the Rev. H. H. Johnson, Rector of the Grey Institute and

-54-

Incumbent of Trinity. The latter offered to take me as a boarder on moderate terms which I accepted at once as the local boarding houses were supposed to be very inferior. Both Pickering and Johnson were chess players, much to my advantage. Port Elizabeth was in a primitive stage. The landing facilities were archaic, the streets wind-swept, sand storms frequent, drinking water scarce, telegraphic facilities not yet available and not a mile of railway even projected in the Eastern Province. There was, however, a fair Library and a Race Course and Cricket Ground but no Club.A public park and Gardens were under discussion and a water supply was the dream of one or two of the more sanguine of the inhabitants. But with all its deficiencies it was a cheery spot with a progressive tone about it which promised well for its future. There were, of course, gradations of society, but they were not very rigid. Of pretentious entertainments there were none, unless on the infrequent visit of a man-of-war or the more infrequent visit of the Governor. But there was much informal hospitality and friendliness and when young men were asked to “drop in of an evening” the invitation was meant seriously and accepted readily.

In 1866 – I forget the month – I attended an evening meeting to discuss the formation of a Club to be called the P.E. Club and the project was unanimously agreed to with the result that today I am the only surviving original member. It is not too much to say that the Club throughout its existence has been a power for good and enabled billiards and cards to be played under an influential committee instead of young men having to resort to public houses and worse. The Club has also been a centre of hospitality, entertaining hundreds of distinguished visitors in the course of its career. Later on the River Club was also founded at the Red House on the Zwartkops River, where I have spent many a happy day fishing,

-55-

yachting and bathing. Still later there started or was revived an amateur Dramatic Society of which Mr. H.W. Pearson was the stage manager, until he became Mayor and Member of the assembly. Mr. (afterwards Sir Frederick Blaine) was for years our star performer and indeed was an accomplished actor. We not only enjoyed ourselves hugely but netted a fair annual profit for local charities. The world went very well then but now, beyond myself, there are very few survivors of those golden days. Sport was vigorously pursued. I was a rather ineffective member of the Cricket Club but was in the first 15 at football.

Scribbling was, I fear, always a vice of mine and was of a desultory character but possibly it kept me out of other and more harmful pursuits. I see, for instance, that on 27th July 1869, I addressed a letter to the London “Times” deprecating the rumoured withdrawal of the Imperial Troops from South Africa. My argument was perhaps somewhat faulty, but the “Thunderer” in a leading article was more sympathetic than I merited and, as we know, the withdrawal only took place in 1922 by which time we had a Defence Force of our own.

My grandfather died on 22nd November 1868 and I still possess letters from my two aunts dated 4th February 1869 – the last I ever received from “Calenick” – announcing their decision to retire to Falmouth so as to be near the Bentleys.

An occasional walking tour, especially at Easter, was one of my greatest pleasures. I had only one friend who shared my views on this point, but he was resourceful, untiring and therefore a tower of strength. Memory recalls one such trip in particular. We left Port Elizabeth on a Thursday afternoon and walked to an old house near Kragga Kamena, unoccupied, but to which we had permission to go. It was reputedly haunted owing to a tragedy that occurred there in old slave days, but the caretaker who gave us the key, declined with emphasis to enter the house after dark. Indeed, we had a night of adventure for the place was full of strange

-56-

noises and it was only after firing a pistol in the attic that we induced the guests – I may as well say rats – to leave us in peace.

The next morning we crossed the Dunes, i.e. the sandhills and came out on the shores of St. Francis Bay, along which we walked until sunset, sleeping on the beach in our blankets. The next morning we bathed in a long pond in company with a seal of which, at first, we fought shy. Saturday afternoon overtook us at the mouth of Van Staadens where we borrowed a leaky boat and partly by river and partly through the wood, reached Mrs Cadle’s Hostelry, the honeymoon cottage of the whole district. This place, which no longer exists, deserves some comment here. It was one of the institutions of the district, situated at the head of the Van Staadens River pass, a little off the main post-road to Cape Town. The area was thickly wooded, the river a winding one full of boulders, and the hostelry the cheeriest, cleanest, and most comfortable one within our reach at Port Elizabeth.

The philosophic poet who “found his comfort at an Inn” would here have been at home. The scenery, the mountain air and the cuisine were all delightful and no warmer heart ever beat in the breast of a wayside hostess than in the ample figure of Mrs Cadle. She shared, with Mrs. Johnson, of the Nezaar, the benediction of all travellers. Peace be with both of them in grateful memory of auld lang syne.

On Sunday we walked up the river to its source and tramped the Tittelklip Hills and over the Zwartkops River to Uitenhage, reaching home the next day after a journey of at least 100 miles.

In 1870 we heard of the loss of the turret ship “Captain” in the Bay of Biscay. An almost daily visitor at our bachelor’s quarters was a young fellow, Peter Heugh, of Dutch descent, whose brother was an assistant paymaster’s clerk on board the ill-fated ship. There was no cable in those days, but I telegraphed to Cape Town to ascertain the fate of

-57-

the lad and he proved to be one of the victims of the disaster. I still possess the message which I had to break to my friend. He too has since passed away, the same cheery fellow to the end. As I have said, there were drawbacks to life at Port Elizabeth in those days. It was a very hard drinking place, it was wind-swept and dusty, the soil shallow, the trees stunted, amenities few. But it was never slow. The inhabitants possessed a healthy spirit of discontent and strenuously applied themselves to secure improvements, threatening the Government at Cape Town with secession if their demands were not met. Under this stimulus, the bi-weekly post was accelerated, telegraphic communication was promised, and a few years later, railway engineers arrived to examine the possibilities of a railway. What perhaps interested us more than these was the formation, or reformation I forget which, of the Harbour Board. Under its auspices a long wooden jetty was erected with a cross section at the ocean end of it, and for a time cargo and passengers were landed in comfort and safety. But the Port authorities had no Marine Engineers on their staff and entrusted the work to an architect, who entirely overlooked the question of the sand travel under the influence of the prevailing current, with the result that the pier acted as a reclamation effort in which direction it was extremely effective and ere long the silting of the sand threatened to ruin the port. The Government then had to come to our rescue and the eminent authority, Sir John Coode, visited Port Elizabeth in 1875, and reported on its needs. His recommendation was that the old structure should be entirely removed and replaced by open work that enabled the sand to pass, and in due time the working of the Port was intensely facilitated, though it will probably never be an easy task to erect Docks equal to those at other places in South Africa. In the following year, Sir John sent out a Resident Engineer, Mr Shield, a capable man who had married his

-59-

daughter. The Coode Family were Friends of my great hostess, Mrs. Hodge, and her letter of introduction gave us the pleasure of knowing the newcomers.

In the days of which I now wrote inter-port jealousies were much in evidence. Port Town for a generation or more ruled supreme. The mail steamers came no further but transshipped cargo to smaller boats. Double handling is, of course always a handicap to business. When at length scientific jetties and a sea wall were provided at Algoa Bay, the supremacy became acute. The crazy idea was held that one port could only hope to thrive by the ruin of another. The expansion of trade was not allowed for. Gradually, however, with its modern equipment, Port Elizabeth became the distributing centre for the vast interior. Its merchants viewed with tolerant disdain the strenuous effort of the Hon. W. Cock of Port Alfred to make his little port – the Kowie – serviceable for lower Albany. In the end his scheme failed and he lost his money but his name deserves honourable mention. He had been one of the sturdy settlers of 1820 and was a man of great energy but rather in advance of his time. In the “seventies” the imports and exports of Port Alfred aggregated a quarter of a million sterling in value, but the Government of the day was parochial in its outlook and refused to assist in developing the port and Mr. Cock, beaten, and I fear, broken, retired from the contest. The present Sir Thomas Smartt, when Commissioner of Public Works, in 1900, obtained a report on the scheme from a competent engineer, but the project was again shelved and even now nothing has been done. The most formidable claim of East London, though fiercely opposed, met with greater success and won its place in the sun, without appreciably damaging existing harbours. In truth there was room for them all. But then came an unholy alliance between the three leading Cape ports which, laying aside ancient feuds, combined in protesting against the ambition of Natal to have a port of its own at Durban. The controversy was a warm one but Natal possessed a strenuous

-59-

champion in Escombe, who was supported in the press by Sir John Robinson and by the Colony at large. The struggle was succeeded by another and tougher one against the natural obstacles which were exceptionally formidable, but energy and human will prevailed and the port now promises to take front rank among the harbours of the Union of South Africa. But strife was not over. Delagoa Bay, though for the time in foreign hands, is the natural port of the Transvaal Province of the Union, then of course a Republic. Its development was steadily opposed by all other vested interests, especially when Kruger ceded the railway rights to a Hollander Company. But no Chamber of Commerce speeches or press leading articles were able to arrest the march of progress and it is now an axiom that healthy inter-port rivalry is all to the good.

During my residence at Port Elizabeth I travelled extensively and thus became acquainted with the various ports, but on only one occasion did I land at Port Alfred. We arrived there at daybreak one summer morning in one of the smallest of the coasting steamers. I was the only passenger for the port without anchoring, at the mouth of the river, but the Captain whistled for the port boat in vain. Being overdue and in a hurry, he placed me with my baggage on board a lighter conveniently there in charge of a native and with a final angry blast of his siren, he departed in a cloud of swear words. It was some hours before I was rescued and a lighter in a swell is an unsteady platform, but I had an excellent time of it for the boatmen initiated me into the – to me – new game of catching shark with a j line and a belt of red flannel. We both had good sport but I spoilt a suit of clothes. The Port authorities were very indignant at the Captain’s slight to their cherished port and also at my refusal to sue the company for desertion and consequential damages.

Passengers who landed at East London in those days will remember the sensation of being dropped over the ship’s side in a basket, which had a trick of revolving in a giddy

-60-

fashion before it arrived on the deck of the lighter alongside. I once travelled with General Booth, the founder of the Salvation Army, and saw him so transferred. He wore a top hat which is not the best of headgear during gymnastic exercises. The basket struck the deck of the lighter with unwanted force which I trust was accidental. For a moment the General lost his hat, but not his dignity and his reception by a gathering of Salvation Lasses was most enthusiastic. I once had a worse experience on Durban Bar at a time when all mail boats still had to lie outside. We were in a lighter and being towed in by a tug, which grounded for some time. Fortunately we had been battened down below, but the noise of the breakers was not pleasant especially when our lights went out. The squalls that occasionally struck us were not the only squalls I heard.

To revert to Port Elizabeth, there were several residents in its early days who would have been outstanding figures anywhere. Among them, James Somers Kirkwood, ranks high in my memory. His was a far-seeing mind with visions as vivid as those of Rhodes, but without the practical business instincts of the latter. In conception, he too was a “dreamer devout” but in execution he was weak. Some of his schemes came to fruition after his death, and I think he and Rhodes in combination would have been irresistible. His plans for irrigating the Sundays River Valley have since been effected and I remember how his faith infected a staid and cautious Bank Manager like myself. On one memorable occasion he personally conducted me over the whole area and I found his enthusiasm very infectious. Nor have I forgotten that while resting under a tree at midday, he recited “Orion” from the first line to the last with a vivacity I admired in spite of the pitiless heat.

Before returning to Port Elizabeth, he drove me to Enon, the Moravian Mission Station, a tranquil spot, which had “gone dry” before the pussy-foot era, and was refreshingly quiet as a result. I was introduced to the oldest inhabitant, a shrivelled up native who when interrogated as to his length of residence

-61-

replied through an interpreter that he had always been there. Another versatile genius at Port Elizabeth was Wm. Fleming, meant by nature to be chief constructor to the Admiralty, converted by unkind fate into a commercial magnate for which he was unfitted. He could build a ship, paint a boat, construct a ship and sail a ship, indeed his knowledge of the theory and practice of marine architecture was very exceptional and a parent has much to answer for who fails to recognize and encourage the bent of the mind of a clever lad. We have to thank Fleming for being the first man to exploit the sole fishery on the Agulhas Bank and he closed his career by making an excellent Mayor of Town 1881-1882.

In 1875 we had a great revolution in Church matters by the retirement of the Colonial Chaplain, my good friend Pickering, who was succeeded by a young priest of 29, the Rev. Theodore Wirgman, an irrepressibly active high churchman, a great upholder of the Oxford movement and full of life and vigour. His disturbance of the old sleepy condition of affairs was profound. His introduction of vestments, a surpliced choir and Gregorian music were anathema to his congregation and his zeal was quite untempered by discretion. But he had a strong will, pleasant manners and considerable personal charm, and after a stern contest, he prevailed in his struggle against evangelical apathy. He was a born fighter and I took to him from the first. His biography describes me as his only whole-hearted supporter. And indeed, he deserved it. He built several new churches in and around Port Elizabeth, opened schools and in every way brought the Church and the people into closer relations, was in the forefront of every movement socially and politically. He had his faults as every man of action had, but I loved him for his many virtues and he has left his mark on the communityto a greater extent than they know. His volcanic energy shortened his life, but his work once done has been permanent

-62-

and his memory is an inspiring one. May he rest now in peace, as he never rested, or rusted, here.

We enjoyed our bathing at Port Elizabeth for many years under the friendly tuition of a really great master, James Gronalt by name, and I believe by nationality, a Dane. His charm of manner was exceptional and made him very popular. He was powerfully built and walked as if he were web-footed,for water was his true element. In the water and under the water, he was supreme, but he used humorously to declare that he did not feel safe on shore. His presentiment was just, for, later on, he was killed by a lion. But the time came when sea bathing in Algoa Bay received a rude shock, for the place was invaded by man-eating sharks, one of whom, at a crunch, severed a leg from the body of a local resident named Ludwell, close to the very steps of the Jetty. After which bathing was taboo, except to Gronalt who continued his favourite pursuit, armed with a formidable knife. I remember that shortly after this date, a local German, met with what he inaptly called “A similar incident”. He was staying at the River Club on the Zwartkops, a tidal river, and one very warm afternoon he fell asleep on the little jetty and slipped into the river. His yells disturbed the peace of the Club and it required our united assurance to convince him that he had not been “sharked”.

Two other notable personages in those days were Captain Frank Skead, R. N., the Harbour Master, and a B. Ladds, R.N.E., of the Union Steamship Company’s service, called respectively North Pole Skead and South Pole Ladds, the first because he had taken part in one of the numerous expeditions to discover the fate of Sir John Franklin; the second because he was an extremely cautious mariner with a rooted dislike of the rocky coast, so that when bound for Table Bay, he always steered as if his destination was Australia or the Antarctic.

But both were gentlemen in the best sense of the word and no account of “the Bay” would be complete without mentioning them. When the great earthquake in the Straits of Sunda occurred in August 1883 and Krakatoa was rent in twain,

-63-

the effects were world-wide. At Port Elizabeth there was a night watchman on the Jetty employed by the Harbour Board. One of his duties was to register high and low water. A few days after the explosion he reported to the Board the occurrence of three high tides during the preceding night. Unnaturally he was suspended for being drunk while on duty, but was reinstated a few days later when cables arrived announcing that the strange phenomenon had been observed in all Eastern waters. Later on many strange fish unknown before began to haunt our coast, some of them of the quaintest shape and most brilliant colouring. Later still pumice stone arrived in incredible quantities, littering our beaches, and the sunsets were for months obscured by a strange fantastic mist.

Among acquaintances and friends at Port Elizabeth, I must not omit Dr. Fred Ensor, who was fonder, I think, of literature than of surgery, and who, as a well-read man, was somewhat of a rarity in our commercial atmosphere. I recall also the arrival of a youngster as a representative of the machinery magnates, the Howards of Bedford. His first appearance at our Sport Club was a veritable triumph for he carried everything before him. He was then unknown to fame but subsequently made a fortune on the Gold Fields, took an active part in Transvaal politics, was condemned to death by Kruger but released to eventually die for his country in the Great War. When I add that some time prior to his death he received a Baronetcy, South Africans will guess that I am referring to Sir George Farrar, a lovable character who played many parts on the stage of South Africa. Anyone who had the privilege, as I had, of knowing his venerable mother who outlived him will have had no difficulty in guessing from whom he derived his great abilities. My last ascent of Table Mountain was made in Sir George’s company, and I recognized that day that my climbing days were over.

The late Hugh Cameron Ross, my predecessor in the Standard Bank, concealed under a bluff demeanour, a kinder heart than nature usually bestows on the sons of men. His

-64-

great friend was Matthew Jennings, the Collector of Customs, a quaint, punchy figure, but a man of infinite good humour. The pair were bachelors and inseparable. On one occasion we three, though poor sportsmen, nearly lost ourselves in the Addo Bush where we went to hunt Buffalo. In this event the buffalo hunted us and Jennings climbed a tree, looking so Pickwickian that we laughed uproariously, which seemed to scare the buffalo more than our guns. On a subsequent occasion, I had a much nearer shave in the bush, for a friend, named Emerson, and I, on horseback, were irascibly chased one Sunday afternoon by a couple of small vicious elephants and striking the main road only just enabled us to get away alive. Other memories of the Eastern Province crowd pleasantly upon me as I write but I must reluctantly pass them by.

Page 48

Chapter IV: LONDON AND SOUTH AFRICA : 1863-1864.

On the first day of August 1863, a few days before my 21st birthday, I entered the service of the London and South African Bank at 10 King William Street, adjoining Ridgways, the Tea Merchants. There for six months I made a pretence of working with two other probationers, one of them with the very English name of Hampden Hume, the other a typical Scot known as Sandy Hay. The salary was £100 a year but I paid my way on it and even remitted something to my mother. Our training was slack and ineffective and I picked up little banking practice that I had not already acquired at Penzance.

The Work, such as it was, left time for odd hours of relaxation which so far as Hay and I were concerned, consisted of fencing bouts in a back room. Occasionally the delivery or collection of Bills of Exchange took me to the offices of the Bill Brokers, Hichens and Harrison and Foster and Braithwaite, both firms, I believe, are still in existence.

My modest lodgings were quiet ones at No.18 Myddleton Square, Clerkenwell. My landladies were two maiden ladies no longer young who, I think, had seen, like the Square, better days. They furnished me together with a latch key, a few appropriate remarks on the advantage of sobriety and early hours and they made an effort to teach me how to coax the sitting room clock to go, but that ancient time-piece had views of its own and refused to regard my overtures as serious. But my hostesses were entirely to my liking. They were like Charles the Second’s model courtier, never in the way and never out of the way, and when we finally parted it was with expressions of mutual esteem. Fortunately for their peace of mind and probably more fortunately for my own, I was a great reader and quite content with my own company. Moreover

-Page 49-

I had two friends, to whom I still feel that I owe much, sons of my late “Baas” Mr. Courtney of Penzance. One of them,- Leonard, a Barrister, had made his mark at Oxford and was now on the staff of the “Times” the other, William Brideaux, was a clerk in the office of the Ecclesiastical Commissioners.

Their quiet quarters were in Bowes Place, Great Ormond Street, and I was made free of them to my great advantage. There I played chess, had the benefit of a good library and met many men who had since done well in Church and State. Both my friends have since passed away. But notwithstanding the “want of pence,” which vexes private as well as public men, I managed to see something of the sights and sounds of London, and I once saw at Opera or Theatre a then very handsome pair of sisters idolized by the people, the Princess of Wales and Princess Dagmar. Their brother, Prince George, was with them.

For them, as for all of us, much water has passed under the bridges since that night. Amongst the singers then in their prime I heard Sims Reeves, Santley, Adelina and Carlotta Betti, Bettini, Bossi, Trebelli, Parepa and many others. Among conductors I recall Julien, Benedict, Manns and Arditi; among organists Goss and Coward; and among other musicians Sir Charles Halle, Arabella Goddard, Dannreuther, Sivori, Lotto, Webb and Ries. Of actors I saw but few, but among those few were Phelps, Charles Kean, Fechter, Sothern and Buckstone. The last named has left, I think, no successor, For in comedy, as distinguished from farce, he was without a rival. Even now in visions of the past, I often recall his inimitable characterisation of parts he had made his own, especially in Sheridan’s plays. I have long since lost my love of the theatre, indeed the theatre seemed to have been brushed aside by the Music Hall and the Music Hall is now being jostled by the Cinema. But I still laugh sometimes when I remember Buckstone and I know I shall never look upon his like again. May the earth lie lightly on the graves of all who provide, as he did, honest amusement, without taint of vice or vulgarity, for the ever growing masses who

-Page 50-

gravitate towards city life. Public entertainers of Buckstone’s type are as necessary and useful as the pulpit or the press,and deserve more from us than they receive. Speaking of the pulpit reminds me that during my six months in London, I cannot recall the names of any preachers who had the gift of persuasive oratory, but perhaps my recollection of Hedgeland was too recent to admit of my doing justice to the London “high and dry” Divines.

But I did hear one indubitably great orator in Henry Ward Beecher who spoke one night in Exeter Hall on the vexed question of the day, the right of the Southern States to secede from the North on the slavery issue. Leonard Courtney, I think, was on Beecher’s side; his brother and I were for the picturesque Southerners. Exeter Hall has long since passed away, but my memory still holds the smallest details of that evening, the densely crowded Hall, the mixed sympathies of the audience and its gradual conquest by the dominant personality of the great orator, whose voice, now flute-like, now peeling in organ tones, gradually prevailed over prejudice and passion. He played upon us as a master plays on a musical instrument and ere long we were all as children in his hands. It was a memorable night and has had no successor of equal intensity.

As indicating the survival at this time of old customs that have since passed away, I find that I wrote to Mrs. Hodge that on 5th November 1863 “Guy Fawkes, the rope and President Lincoln had been duly burnt in effigy”.

Towards the close of 1863, it was intimated to Hay and myself that we should be required to proceed to our destination early in the new year. One memorable day, therefore, I was called before the Board to receive their farewell instructions. Perhaps I felt rather abashed at the flow of advice given by the Directors in seriatim. It was doubtless good but there may have been too much of it. At all events this was on the mind of one member of that August

-51-

body, for on my having “leave to depart” and in a great hurry to do so, he whispered as I shook hands

“And when you feel ill on board take a nip of brandy”. This entirely human utterance drove away my nervousness and I followed his advice, even if I forgot that of all the others. The speaker was that fine old German gentleman Mr. Adolph Rosenthal, from whose son Harry, also now dead, I received much kindness both in Port Elizabeth and London.

I embarked on the U.S.S.Co’s “Briton” at Plymouth on 6th February 1864. The weather was exceptionally wild and I gladly draw a veil over our first week at sea. The “Briton” was a roomy sailing ship with an auxiliary screw and her tonnage was about 800. The contract time was 42 days and we made the passage in 38, calling nowhere and indeed never seeing land until Table Mountain appeared on the horizon. The day of the luxurious liner had not arrived There were few passengers and the principal figure on board was not Captain Boxer but his wife. There were no deck games barring a noisy “bull board”, the food was plain and the only liquor a peculiarly indifferent one known as Carston’s Bristol Ale. I do not remember passing any other steamer, but on one occasion we saw a sight which for picturesqueness beat any steamer that ever was launched for we met three China Tea Clippers homeward bound, with a fair wind and an enormous cloud of canvas, than which there is no finer sight on sea or land.

We were very proud of our achievement in arriving three or four days under contract time, especially when a congratulatory gun was fired at Sea Point from the residence of that cheery veteran, Captain Harrison, the Company Agent. I was glad to be on shore again and to sleep in a real bed again. The lodging house was in Roeland Street but I have no record of the landlady’s name and even the house is unrecognizable. Of course, Hay and I at once started off, like all newcomers, to ascend Table Mountain and we made a

-52-

miserable failure of it. The next morning I called on the Governor, Sir Philip Wodehouse, to present a note of introduction to Lady Wodehouse, from Mrs. Michell Hodge and Their Excellencies were very gracious. He sailed a few years later to occupy the Governorship of Bombay, but his wife died before he left these shores and lies in a somewhat neglected grave in Rondebosch Churchyard. Sir Philip was the first Governor of the Cape I met; thence onward I knew a long succession of them until the line ended with Sir Walter Hely-Hutchinson in 1909.

Of course I called on the Cape Town Manager of the Bank, Mr. C. M. More, a fine upstanding figure of a man and I believe an excellent Banker. His office in Adderley Street is now a tobacconist’s shop. He was good enough to “inspan” me at once by entrusting me with a consignment of specie for the Wellington Branch 40 miles away. I returned the same day having traversed in a few hours the whole railway system of South Africa, which now amounts to over 15,000 miles. In those early days the suburban line to Wynberg was then only partly constructed, but was approaching completion, and was officially opened the month after my arrival. As a curiosity, I subjoin the following notice that appeared in the “S.A. Advertiser and Mail” of 30th April 1864:-

THE WYNBERG RAILWAY

Notice is hereby given that the Railway between the Salt River Junction and Wynberg,

Will be OPENED FOR PUBLIC TRAFFIC ON MONDAY NEXT THE

2nd MAY.

Trains will run between the Salt River Junction and Wynberg in connection with trains on the Cape Town and Wellington Railway as follows:

Leaving Cape Town at 7.00. and 10.50 a.m. and 5.50 p.m., and Wynberg at 8.10 and 12.50 p.m.and 4.40 p.m.

Fares from Cape Town to any Station on the Wynberg Railway, One shilling each, without distinction of Class, and the like fare from any Station on the Wynberg Railway to Cape Town.

The trains will call at the following intermediate stations on the Wynberg Railway, viz: Mowbray, Rondebosch, Newlands and Claremont.

By Order of the Board of Directors

JOHN STEIN Chairman.

CAPE TOWN, 28th April 1864.

-53-

The Cape Town I saw in 1864 has changed a great deal since I arrived. Stoeps then disfigured nearly all the principal thoroughfares including Adderley Street. The Malays were the only picturesque people to be seen. They were almost the sole drivers and the immense hats they wore are now altogether in disuse. Walking they used wooden sandals with a nail between the great toe and its neighbour. They carried their dead to their own cemeteries however distant, until railways came and with them a declaration by their great ecclesiastical authority that their use was permissible because they were not wheeled vehicles within the meaning of the Koran, as the wheels were not of wood. There is one point about our South African Malays which at once struck me and which even now remains.

They are wonderfully abstemious as well as industrious in both which respects they give a good example to many white people. It is true now as on the day I landed.

We were only a few days in Table Bay before proceeding to our final destination, Algoa Bay, then the terminus for the mail boats. Beyond this, small coasting steamers were used. I can vividly remember our landing in a surf boat amid what appeared appalling breakers. Our coxswain, a Greek named Messina, steered in a masterly manner and though today in a very superior position as a boat owner, he is still in harness and about the only man at Port Elizabeth who remains of all those whose acquaintance I made on my arrival. The place was singularly unattractive to a newcomer. I was bound by my indenture to remain in the Bank for five years and I little thought I should remain at the Port for 21 years and leave it with regret.

We never know what Fortune has in store for us and it would often be a duller world if we did. The Bank was in its infancy, its Manager, Miller, a rough but competent representative. I think the first acquaintance I made was the Rev. W. Pickering, Colonial Chaplain and Rector of St. Mary’s; and he introduced me to the Rev. H. H. Johnson, Rector of the Grey Institute and

-54-

Incumbent of Trinity. The latter offered to take me as a boarder on moderate terms which I accepted at once as the local boarding houses were supposed to be very inferior. Both Pickering and Johnson were chess players, much to my advantage. Port Elizabeth was in a primitive stage. The landing facilities were archaic, the streets wind-swept, sand storms frequent, drinking water scarce, telegraphic facilities not yet available and not a mile of railway even projected in the Eastern Province. There was, however, a fair Library and a Race Course and Cricket Ground but no Club.A public park and Gardens were under discussion and a water supply was the dream of one or two of the more sanguine of the inhabitants. But with all its deficiencies it was a cheery spot with a progressive tone about it which promised well for its future. There were, of course, gradations of society, but they were not very rigid. Of pretentious entertainments there were none, unless on the infrequent visit of a man-of-war or the more infrequent visit of the Governor. But there was much informal hospitality and friendliness and when young men were asked to “drop in of an evening” the invitation was meant seriously and accepted readily.

In 1866 – I forget the month – I attended an evening meeting to discuss the formation of a Club to be called the P.E. Club and the project was unanimously agreed to with the result that today I am the only surviving original member. It is not too much to say that the Club throughout its existence has been a power for good and enabled billiards and cards to be played under an influential committee instead of young men having to resort to public houses and worse. The Club has also been a centre of hospitality, entertaining hundreds of distinguished visitors in the course of its career. Later on the River Club was also founded at the Red House on the Zwartkops River, where I have spent many a happy day fishing,

-55-

yachting and bathing. Still later there started or was revived an amateur Dramatic Society of which Mr. H. N. Pearson was the stage manager, until he became Mayor and Member of the assembly. Mr. (afterwards Sir Frederick Blaine) was for years our star performer and indeed was an accomplished actor. We not only enjoyed ourselves hugely but netted a fair annual profit for local charities. The world went very well then but now, beyond myself, there are very few survivors of those golden days. Sport was vigorously pursued. I was a rather ineffective member of the Cricket Club but was in the first 15 at football.

Scribbling was, I fear, always a vice of mine and was of a desultory character but possibly it kept me out of other and more harmful pursuits. I see, for instance, that on 27th July 1869, I addressed a letter to the London “Times” deprecating the rumoured withdrawal of the Imperial Troops from South Africa. My argument was perhaps somewhat faulty, but the “Thunderer” in a leading article was more sympathetic than I merited and, as we know, the withdrawal only took place in 1922 by which time we had a Defence Force of our own.

My grandfather died on 22nd November 1868 and I still possess letters from my two aunts dated 4th February 1869 – the last I ever received from “Calenick” – announcing their decision to retire to Falmouth so as to be near the Bentleys.

An occasional walking tour, especially at Easter, was one of my greatest pleasures. I had only one friend who shared my views on this point, but he was resourceful, untiring and therefore a tower of strength. Memory recalls one such trip in particular. We left Port Elizabeth on a Thursday afternoon and walked to an old house near Kragga Kamena, unoccupied, but to which we had permission to go. It was reputedly haunted owing to a tragedy that occurred there in old slave days, but the caretaker who gave us the key, declined with emphasis to enter the house after dark. Indeed, we had a night of adventure for the place was full of strange

-56-

noises and it was only after firing a pistol in the attic that we induced the guests – I may as well say rats – to leave us in peace.

The next morning we crossed the Dunes, i.e. the sandhills and came out on the shores of St. Francis Bay, along which we walked until sunset, sleeping on the beach in our blankets. The next morning we bathed in a long pond in company with a seal of which, at first, we fought shy. Saturday afternoon overtook us at the mouth of Van Staadens where we borrowed a leaky boat and partly by river and partly through the wood, reached Mrs Cadle’s Hostelry, the honeymoon cottage of the whole district. This place, which no longer exists, deserves some comment here. It was one of the institutions of the district, situated at the head of the Van Staadens River pass, a little off the main post-road to Cape Town. The area was thickly wooded, the river a winding one full of boulders, and the hostelry the cheeriest, cleanest, and most comfortable one within our reach at Port Elizabeth.

The philosophic poet who “found his comfort at an Inn” would here have been at home. The scenery, the mountain air and the cuisine were all delightful and no warmer heart ever beat in the breast of a wayside hostess than in the ample figure of Mrs Cadle. She shared, with Mrs. Johnson, of the Nezaar, the benediction of all travellers. Peace be with both of them in grateful memory of auld lang syne.

On Sunday we walked up the river to its source and tramped the Tittelklip Hills and over the Zwartkops River to Uitenhage, reaching home the next day after a journey of at least 100 miles.

In 1870 we heard of the loss of the turret ship “Captain” in the Bay of Biscay. An almost daily visitor at our bachelor’s quarters was a young fellow, Peter Heugh, of Dutch descent, whose brother was an assistant paymaster’s clerk on board the ill-fated ship. There was no cable in those days, but I telegraphed to Cape Town to ascertain the fate of

-57-

the lad and he proved to be one of the victims of the disaster. I still possess the message which I had to break to my friend. He too has since passed away, the same cheery fellow to the end. As I have said, there were drawbacks to life at Port Elizabeth in those days. It was a very hard drinking place, it was wind-swept and dusty, the soil shallow, the trees stunted, amenities few. But it was never slow. The inhabitants possessed a healthy spirit of discontent and strenuously applied themselves to secure improvements, threatening the Government at Cape Town with secession if their demands were not met. Under this stimulus, the bi-weekly post was accelerated, telegraphic communication was promised, and a few years later, railway engineers arrived to examine the possibilities of a railway. What perhaps interested us more than these was the formation, or reformation I forget which, of the Harbour Board. Under its auspices a long wooden jetty was erected with a cross section at the ocean end of it, and for a time cargo and passengers were landed in comfort and safety. But the Port authorities had no Marine Engineers on their staff and entrusted the work to an architect, who entirely overlooked the question of the sand travel under the influence of the prevailing current, with the result that the pier acted as a reclamation effort in which direction it was extremely effective and ere long the silting of the sand threatened to ruin the port. The Government then had to come to our rescue and the eminent authority, Sir John Coode, visited Port Elizabeth in 1875, and reported on its needs. His recommendation was that the old structure should be entirely removed and replaced by open work that enabled the sand to pass, and in due time the working of the Port was intensely facilitated, though it will probably never be an easy task to erect Docks equal to those at other places in South Africa. In the following year, Sir John sent out a Resident Engineer, Mr Shield, a capable man who had married his

-59-

daughter. The Coode Family were Friends of my great hostess, Mrs. Hodge, and her letter of introduction gave us the pleasure of knowing the newcomers.

In the days of which I now wrote inter-port jealousies were much in evidence. Port Town for a generation or more ruled supreme. The mail steamers came no further but transshipped cargo to smaller boats. Double handling is, of course always a handicap to business. When at length scientific jetties and a sea wall were provided at Algoa Bay, the supremacy became acute. The crazy idea was held that one port could only hope to thrive by the ruin of another. The expansion of trade was not allowed for. Gradually, however, with its modern equipment, Port Elizabeth became the distributing centre for the vast interior. Its merchants viewed with tolerant disdain the strenuous effort of the Hon. W. Cock of Port Alfred to make his little port – the Kowie – serviceable for lower Albany. In the end his scheme failed and he lost his money but his name deserves honourable mention. He had been one of the sturdy settlers of 1820 and was a man of great energy but rather in advance of his time. In the “seventies” the imports and exports of Port Alfred aggregated a quarter of a million sterling in value, but the Government of the day was parochial in its outlook and refused to assist in developing the port and Mr. Cock, beaten, and I fear, broken, retired from the contest. The present Sir Thomas Smartt, when Commissioner of Public Works, in 1900, obtained a report on the scheme from a competent engineer, but the project was again shelved and even now nothing has been done. The most formidable claim of East London, though fiercely opposed, met with greater success and won its place in the sun, without appreciably damaging existing harbours. In truth there was room for them all. But then came an unholy alliance between the three leading Cape ports which, laying aside ancient feuds, combined in protesting against the ambition of Natal to have a port of its own at Durban. The controversy was a warm one but Natal possessed a strenuous

-59-