WW2 was fought across the oceans of the world. As such the seas off Port Elizabeth were not immune from the depredations of the scourge of the seas: the U-Boat. One such vessel that was sunk off the Eastern Cape coast was the Liberty Ship, the Anne Hutchinson.

The American Liberty ship Anne Hutchinson SS was torpedoed and shelled on October 26th, 1942, by German submarine U-504. Her stern portion up to No. 4 hatch was blown off. The forepart was towed into Algoa Bay on October 31st. Three lives were lost. While near the harbour, the bow portion which had survived intact, attempted to “escape” by drifting down to Plettenberg Bay.

Main picture: Anne Hutchinson after being torpedoed

Details of AttackAt 18:43 hours on 26 Oct 1942 the unescorted Anne Hutchinson (Master John Wilhelm Stenlund of Finland) was hit on the starboard side by two of four torpedoes from U-504 about 60 miles east of East London, South Africa. The U-boat had missed the ship five minutes earlier with a spread of two stern torpedoes because cargo vessel had just done a turn to starboard on her zigzag course after the torpedoes were fired. Lookouts then spotted one torpedo of the second spread pass 20 yards ahead of the vessel, but it was too late to take avoiding action and two torpedoes struck abaft the engine room in the No. 4 hold almost simultaneously. The explosions buckled the side of the ship, created a hole 14 feet by 16 feet, broke the propeller shaft, stopped the engines, knocked out the electrical systems, smashed the wireless set and blew the No. 4 hatch covers off, killing three men sitting on them. These were John Ruedo, Elmer Mehegen and Jack Gottsman.

An oil tank had also been holed, covering the after gun and its crew with oil. However, the bulkheads on either side of the hold remained intact but as the ship was completely disabled the surviving eight officers and 29 crewmen abandoned ship in three lifeboats, followed shortly thereafter by the 17 armed guards (the ship was armed with one 4in, four 20mm and two .30cal guns) in the fourth. At 19.28 hours, a coup de grâce struck the fire room, causing the boilers to explode. The U-boat then surfaced and left the area without questioning the survivors because search lights were seen nearby. Moreover if the Germans wanted to be 100% certain of the cargo ship’s demise, they would first have to reload the torpedoes from the upper deck containers. The Anne Hutchinson was judged to be beyond salvage.

Secret code books

In their rush to evacuate the ship, one vital set of documents was not removed; the ship’s code books. Their non-removal was deemed to be a serious offence subject to a court marshal. As such, It was imperative that these documents be retrieved despite U-Boats still lurking in the area. Instructions were issued to the David Haig, a trawler converted into a minesweeper, under the command of Lt. van Eyssen, to immediately board both halves of the ship and retrieve these documents. Accompanied by the tug, John Dock, and aided by aircraft, acting as guides, the David Haig made for the approximate position of the wreck. In the heavy seas and in the fading light of day, they spotted an object which happened to be the stern of a ship. Of the other half, and larger portion of the ship, there was no trace. With the submarine still lurking in the vicinity and with no guns to protect herself, it was too dangerous for the tug to approach the stern. It was only in the light of the following day that the steamer managed to get within 100 metres of the hull. Shortly afterwards there was a terrific explosion. Before their eyes, the stern shot into the air and then, as if by magic, it disappeared beneath the water.

Now the chase was on for the missing bow section. Lt. van Eyssen reported to headquarters that the bow section had been sighted by a reconnaissance aircraft. With the John Dock they set off in search of the missing bow section. On locating it, van Eyssen attempted to take the minesweeper alongside. This exercise was treacherous and fraught with danger. Lacking balance the larger ship was out of control and liable to change direction in a heartbeat. They attempted on six occasions to close with the Anne Hutchinson but their endeavours were in vain.

On the seventh attempt Sub/Lt Folkes, without a forethought for his safety foolishly took a leap of faith with arms outstretched in an attempt to grasp a pivoting handrail. It was a near run thing. Several other crew members of the David Haig attempted the same death defying jump. All might have come through unscathed but with millimetres from being crushed. Only now could they execute their mission: find the secret code book failing which they would have compromised the security of the Allies in their war against the evil Axis.

When the prime purpose of their operation had been accomplished, the focus of the minesweeper David Haig was amended to tow the wreck to port by itself as the tug had been delayed on other matters. The Boarding party on the wreck managed with considerable difficulty to pass a line to the David Haig as it was still too hazardous to pass a line of 10inch manila rope from one of the wreck’s large hawsers. But at long last the minesweeper – the ex trawler – with the half ship in tow commenced her unhurried journey to Port Elizabeth. One can only understand how arduous yet sedate the pace was when one is aware that the David Haig weighed only 270 tons as opposed to the hulk weighing 5000 tons.

Then the inevitable happened. After two hours of gruelling progress, the towrope snapped. Eventually a towing wire was made fast. Later that day when the lighthouse at Cape Receife came into view, the tug John Dock took over towing duty.

Fate of the Anne Hutchinson

By then it was evident to all and sundry, from Captain Stenlund to the lowest rating, that there was no other option. It had become necessary to abandon ship as she was expected to go under at any moment. Professionally Stenlund ordered the crew to the boat stations, whereupon the life boats were lowered. After abandoning their ship, the crew were loaded into 3 lifeboats whereas the US Navy Armed Guards could be accommodated in one lifeboat. Their destination was the Eastern Cape coast. By maintaining a southerly direction in the warm Indian ocean, the current would propel them at 3 kilometres per hour and by rigging their sails, they could supplement the speed of the current.

When the life boats were still only a short distance from the cargo ship, a second torpedo struck the engine room. As a consequence of this strike, the ship split into two. To the survivors’ surprise and no doubt shock as well, the U-boat surfaced. None could determine the nationality of the submarine. The sub then submerged and was not seen again. By then it was dark and the sea was very rough.

Unfortunately during the night one lifeboat with the second officer, got separated from the other three boats but thankfully its 10 occupants were picked up six hours later by the American steam merchant Steel Mariner ship and they landed in Durban on Wednesday 28 October.

On the night of Tuesday the 27th of October, the remaining survivors in three lifeboats were found by a fishing vessel off Port Alfred which shepherded them to Port Alfred where they landed at dawn the following morning. Two of the survivors had to be treated for minor injuries and the 44 men were later taken to Port Elizabeth where accommodation were arrange for then at the Seaman’s Institute.

The ship’s Master, Stenlund, had a card up his sleeve. He phoned a friend of his in Port Elizabeth, Mr George Wood, my uncle, who was the Branch Manager of an American shipping agent, Robin Lines. Immediately Wood drove out to the Kowie River to pick up his friend.

Blown in half

The Anne Hutchinson stayed afloat and on Thursday 29 October, the South African armed trawler HMSAS David Haigh (T 13) and a harbour tug, the John Dock, attempted to tow the ship to port but were not powerful enough. The most probable reason for the fact that both vessels were unable to tow the Anne Hutchinson was the effort required to overcome the drag of the trailing stern section which was flooded. This breaking action is akin to that of fighter jets which use a parachute to slow the aircraft down. The obvious solution was to place a dynamite charges aft under the ship, which would cut her in two when landing. The aft section swiftly sank allowing the fore section, the bow, to be towed to Port Elizabeth by the armed trawler, arriving there on Sunday 1st

What happened to the bow?

As the ship was torn asunder by the impact of the torpedoes which had struck amid ships, the stern half of the ship sank but remained attached to the bow which remained afloat. That phenomenon evokes the question of why Liberty Ships were prone to split apart in the middle when striking a mine or suffering the effects of an explosive charge. According to Gemini AI “Liberty ships broke in half when hitting mines or suffering other stress because their welded hulls had stress concentration points, especially at the square corners of their large cargo hatches. The mild steel used was also susceptible to a ductile-to-brittle transition in cold North Atlantic waters, and the large, continuous welded seams allowed cracks to propagate easily, turning the force from the mine or explosive charge into a catastrophic fracture.” The essence of the root cause is the fact that Liberty Ships were built in two pieces with the weakest structural point being the connection between the stern and the bow sections.

What exactly happened to the bow when in Algoa Bay is unclear. Presumably with the John Dock and the David Haigh no longer restraining it while in the Bay, the bow then proceeded to steadily drift along the coast past Port Elizabeth. With the bow reported to be missing, the authorities despatched the tug, the John Dock, to retrieve it and tow it back to Port Elizabeth where it would be assessed. Aboard the tug were Mr C.F.S. van der Merwe, another deckhand Dick Campbell and Captain John Stockley.

The following morning George Wood took Stenlund for a drive around Marine Drive to Schoenmakerskop where he had spent spent part of his youth and where he had met his future wife, Kathleen Mary McCleland who lived a few door down at the Hut Tearoom. All of a sudden Stenlund spotted the bow of the Anne Hutchinson bobbing down the coast. As an aside, before the war, whenever Japanese ships came into port, their captain would request a trip along the coast during which they would take countless picture. After the war George speculated what was the reason for this behaviour was. He drew a conclusion that it was for reconnaissance purposes.

Eventually the bow was apprehended by the tug John Dock at Plettenberg Bay. Apparently due to heavy seas, it was only on the following day that the master and two deckhands succeeded in securing a heaving line to the bow portion. By that time, assistance had arrived in the form of a South African naval trawler the David Haigh. According to the book War in the Southern Oceans, the captain of the David Haigh, Lt H.F. van Eyssen, was awarded the MBE for his handling of the affair. When it had dragged the bow section back to Algoa Bay, “kicking and screaming”, the bow was tied up between St Croix Island and the mouth of the Sunday’s River. Here it was stripped of all of its valuable equipment including its funnel.

Recollections of Wood’s wife

Mrs Kathleen Wood recalled that her husband, George, who was also my uncle, took Captain Stenland, who was also a great family friend, for a drive down the coast towards Schoenmakerskop. The captain spotted an object on the horizon and suddenly realised that it was the remaining half of his ship. It was drifting down the coast on the current and Stenlund was anxious as the bow presented a great hazard to shipping since there were no lights on board.

Stenlund then remarked that “Poor Anne Hutchinson. She was burned at the stakes and now she has been blown in two.” The reference to “burning at the stakes” relates to Ann Hutchinson after whom the vessel was named. She was a Puritan spiritual advisor, religious reformer, and an important participant in the Antinomian Controversy which shook the infant Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1636 to 1638.

Incidently, George Wood had a passion for ships and was affectionately known as the “walking encylopedia in shipping”. His hobby was taking photos of ships and wrecks along the coast.

The reason why the remaining portion of the Ann Hutchinson had managed to remain afloat after being sliced into two was that airtight compartments had been built in the centre of the ship. It was this that had kept her afloat. As the condition of the vessel first had to be ascertained, it was not towed into the harbour but instead anchored off the Sunday’s River mouth. Upon inspection she was found to still be seaworthy and then towed closer to the harbour and ultimately into the harbour where salvage work could commence. In PE harbour she was stripped of all her instruments, engine parts, plates and anything else of value. These were later shipped back to the United States.

Swansong

Like much of history, it is recorded long after the event by eye witnesses whose memories are fickle. Not only do they conflate unrelated events but misremember the event partially or even wholly. In this case the prime exemplar is the ultimate demise of the bow of the Anne Hutchinson in which my two prime sources are an article in the EP Herald of 1960 by Adam Brand entitled “They saw ship’s better half” and the book entitled SAS Donkin: The Navy and Port Elizabeth. According to Adam Brand her ultimate end came in a most ignominious manner. The Anne Hutchinson was finally towed into the Bay and used for target practice by the Humewood Battery of the S.A. Coastal Artillery. Guns fired from this battery finally put the last remnants of the Anne Hutchinson to rest at the bottom of Algoa Bay whereas in his book Soelen contends that she was sunk in deep water in Algoa Bay by explosive charges.

Take your pick.

Details of the Anne Hutchinson

Addendum #1

Article by Rosemary MacGeoghan

Rosemary is the daughter of George Wood and is my cousin

Soon after midnight on Wednesday morning, 28 October 1942, George Wood, Branch Manager of Mitchell Cotts, Port Elizabeth, received a telephone call from Port Alfred, notifying him of the arrival of survivors from a stricken ship. They asked if he could please come and make arrangements for the men and to please bring a doctor, as there were some injuries among the men. They told George Wood that lifeboats from the Anne Hutchinson had arrived earlier on at the village of Port Alfred, after sailing up the river.

After ascertaining that it was the Liberty ship, the Anne Hutchison and part of the Robin Line War-time Fleet, George Wood immediately picked up Dr Fred Morrison and the Mitchell Cotts’ Senior Clerk, a Mr. Fred Wilson. They left Port Elizabeth on the Grahamstown Road and at the Nanaga intersection turned off onto a red, dusty road to Alexandria/Port Alfred. George Wood was very grateful to have had Fred Wilson with him as they encountered many farm gates along the way to the Kowie.

Rosemary MacGeoghegan was recently informed by the well-known Bill Deacon, of Bushman’s River Mouth, that in 1942 there had been 27 gates between Nanaga and Alexandria, but he couldn’t remember the number between Alexandria and Port Alfred as it was not a well-used road in those days, as it was too far away.

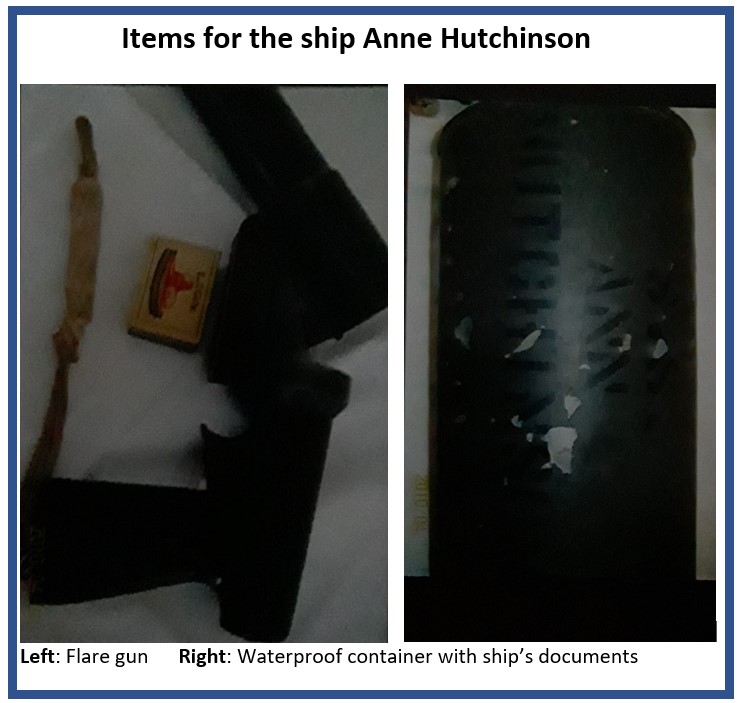

On their arrival in Port Alfred, George Wood met up with Captain John Stenlund and his Chief Engineer (possibly a Mr. Price), while Dr Morrison attended to the injured seamen, one with severe head injuries. Fred Wilson made arrangements to have the seamen transported to Port Elizabeth by train. Captain Stenlund had in his possession a waterproof metal cylinder, with the name SS Anne Hutchinson stenciled on it, containing certain of his ship’s documents that he had brought off the ship during the evacuation. George Wood brought Captain Stenlund, the Chief Engineer and the metal container back to Port Elizabeth. George Wood booked them both in at the Palmerston Hotel while his crew was sent to the Seaman’s Institute. Captain Stenlund spent his first Sunday in Port Elizabeth with the Wood’s family at their Walmer home.

On Sunday 1 November 1942, while on an afternoon drive down to Schoenmakerskop and having just crossed the old railway line with the sea in front of them, both George Wood and Captain Stenlund gasped simultaneously as they spotted an object floating far out on the horizon It was the bows of the Anne Hutchinson passing Schoenmakerskop. The Captain commented with tears on his face, “Poor Anne Hutchison! She was burned at the stake and now she has been blown in half.” From a distance the Bows sticking up out of the ocean resembled the sail of a large sailing ship.

George Wood, realizing the danger she posed in our shipping lanes, immediately returned home and phoned the Port Captain’s office to notify them of the bows drifting the current, towards Cape St Francis. He also phoned Cape Recife lighthouse and learned that they had not seen the bows passing Cape Recife.

Once the bows were secured in the Port Elizabeth harbour, Captain Stenlund boarded his old ship to collect all of his remaining personal items, which included a set of tapestries for his dining room chairs back in the States. Tapestry work had been his hobby while on board the ship.

Captain Stenlund had left the above-mentioned canister together with the ship’s documents in my father’s office until his departure for the States. On leaving PE, the Captain removed his ship’s documents and gave the container to his friend, George Wood.

Rosemary MacGeoghegan nee Wood now still has still waterproof container from the Anne Hutchinson in her possession. Mangold Bros. salvaged the valuable equipment from the wreck and shipped it all the back to the United States. The ship’s funnel was sent intact to the States, lashed to the deck of a Robin Line Ship.

The ship’s wheel was kept for many years by Rosemary MacGeoghegan’s family before passing it onto Simon Fischer, a grandson for George Wood. Simon is restoring the wheel and plans to build it into his lounge overlooking the Vaal Dam

Addendum #2

Anne Hutchinson – Transcription of article in the Herald

This article by Adam Brand appeared in the Herald during 1960

When I asked in this column if anyone knew what became of the bow portion of the US Liberty ship, Anne Hutchinson, which was towed to Port Elizabeth, I did not expect such an excellent response to my question

No less than five people have telephoned me to tell me about the fate of the remaining half of the ship which was torpedoed by U-Boats off the East Cape coast near East London. You will remember that the Anne Hutchinson broke in two after being hit amidships by a torpedo on 29th October 1942. This was at the height of the submarine scare off our coastline during the Second World War. The stern half sank but the bow portion was towed into PE’s harbour 3 days later.

The first caller, a Mr C.F.S. van der Merwe of Sydenham, Port Elizabeth phoned me promptly on the Monday after the article appeared to tell me that he, with two others, was the first man to clamber on board the remaining half of the stricken Liberty Ship.

Subs lurked

He was one of the deck hands on the tug John Dock from Port Elizabeth harbour which was first on the scene to try to rescue the floating half of the ship which was drifting down the coast line towards Plettenburg Bay.

The other two men were the master of the tug , Captain John Stockley and the late Mr Dick Campbell, another deck hand. The John Dock had been warned not to go too near the Anne Hutchinson as aircraft covering the operation had spotted subs lurking in the vicinity.

The John Dock lay at anchor in Plettenberg Bay but the following day a boat was launched and the master Mr. van der Merwe and Mr Campbell boarded Anne Hutchinson and succeeded after great difficulty in securing a heaving line to the bow portion. By that time help had come from the SA Minesweeper, David Haigh.

I learned from the book “War in the Southern Oceans” by Turner, Gordon-Cumming and Retzler that the captain of David Haigh, Lieut. H.F. van Eyssen was awarded the MBE for his handling of the affair.

Next Caller

Mr Van der Merwe told me that Anne Hutchinson was towed into PE Harbour with the bow section sticking up into the air and after being broken up and all valuable parts removed, she was eventually sunk off St. Croix.

My next caller was Mrs K. Wood, wife of the late Mr. George Wood, who at that time was branch manager of the shipping agents in Port Elizabeth for the Robin Line. As a Liberty ship, was part of the Robin Line’s wartime fleet. Mr Wood had a call from Port Alfred where the master of Anne Hutchinson together with a group of officers and men had landed in a lifeboat. Apparently they were overjoyed when they saw that they were near to an inhabited place and were able to sail straight up the Kowie River. Mr Wood drove to Port Alfred and brought Captain Stenlund and some of his men back to town.

Mrs Wood told me that the following day her husband took Captain Stenlund, who was also a great family friend, for a drive down the coast towards Schoenmakerskop. The Captain spotted on object on the horizon and suddenly realised that it was the remaining half of his ship. It was drifting down the coast on the current and presented a great hazard since there were no lights on board.

Captain’s hobby

His remark was “Poor Anne Hutchinson. She was burned at the stakes and now she has been blown in half.” She too told me that after staying in the Port Elizabeth’s harbour for some time and after being stripped of whatever was still useful, Anne Hutchinson was sunk off St Croix. Captain Stenlund was a frequent visitor in the Wood’s home. In his spare time on board, he used to do the most beautiful tapestry work, said Mrs. Wood. Shortly before the torpedoing of his ship, he had completed a set of covers for his dining room chairs in tapestry work. He was overjoyed to that that that still were still undamaged and had not gone down with the stern half of the ship.

Incidentally, the late Mr George Wood had a passion for shoes. He was affectionately known as the walking encyclopaedia on shipping. His hobby was taking photographs of ships and wrecks along this coast.

Huge knife

Unfortunately his very extensive collection of photographs has not been kept intact, Mrs Wood told me. Then Mr Campbell who was a junior clerk with the shipping agents and worked with Mr Wood telephoned me about Anne Hutchinson. He said he remembered her very well and marvelled at how her remaining bow portion had stayed afloat. He said it looked as though a huge knife had cut her in half. It was due to the water tight compartments in the centre of the ship that she was able to keep afloat.

His firm was responsible for the arrangements which were made to strip her of all instruments, engine parts and anything else of value. These were shipped back to the United States. He thought that most probably explosives were attached to what was left of her, and after being ignited, she sank to the bottom of the ocean off St. Croix.

A call from Mr. T.L. Erasmus followed. He said he was working at that time for Mangold Brothers who did part of the demolishing of Anne Hutchinson and he was often on board the half-ship. The first time he saw her when she was floating in the Bay. He was swimming at King’s Beach that day.

Last glimpse

His last glimpse of Anne Hutchinson or rather of what remained of her was the sight of her funnel lashed to the deck of another Robin Line cargo boat on its return to the United States.

For anyone who does not know what a Liberty ship is, by the way, I am told that these were standardised cargo vessels built in the United States as part of lend-lease plan to help Britain fight the war against the Germans. That was before the US actively participated in the war.

But another version of the story was told to me by Mr Wally Simpson, Port Elizabeth’s Beach Manager. At the time when all of this took place, he was serving with the SANF and was stationed at the signals station at the Charl Malan Quay.

Water jug

He said that after being towed in Ann Hutchinson was first of all anchored off the mouth of the Sunday’s river for safety. When her remaining half was found, to be still seaworthy, she was brought closer to the harbour and eventually into the harbour for salvage to commence.

Mr. Simpson as a signalman went on board Anne Hutchinson when she was still in the process of being stripped. As a memento he took ashore a water jug from the Liberty ship which he uses to this day in the office on Humewood Beach. He confirmed that the end came for Anne Hutchinson when she was finally towed into the Bay and used for target practice by the Humewood Battery of the SA Coastal Artillery. Guns fired from this Battery finally put the last remains of Ann Hutchinson to rest at the bottom of Algoa Bay.

Sources

‘https://www.wrecksite.eu/wreck.aspx?32243

‘https://uboat.net/allies/merchants/ship/2294.html

They Saw the Ship’s Better Half by Adam Brand in the E.P. Herald 1960

SAS Donkin: The Navy and Port Elizabeth: By Lt(S) S. van Soelen

My cousin, Rosemary MacGeoghegan

https://www.wrecksite.eu/challenge.aspx?SOUTH_AFRICA

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS_Anne_Hutchinson

Anne Hutchinson (American Steam merchant) – Ships hit by German U-boats during WWII – uboat.net