In this blog, Norman Smith describes the nautical and naval careers of his family. What none of them would anticipate would be the tragedy and trauma arising from this choice of hobby or career.

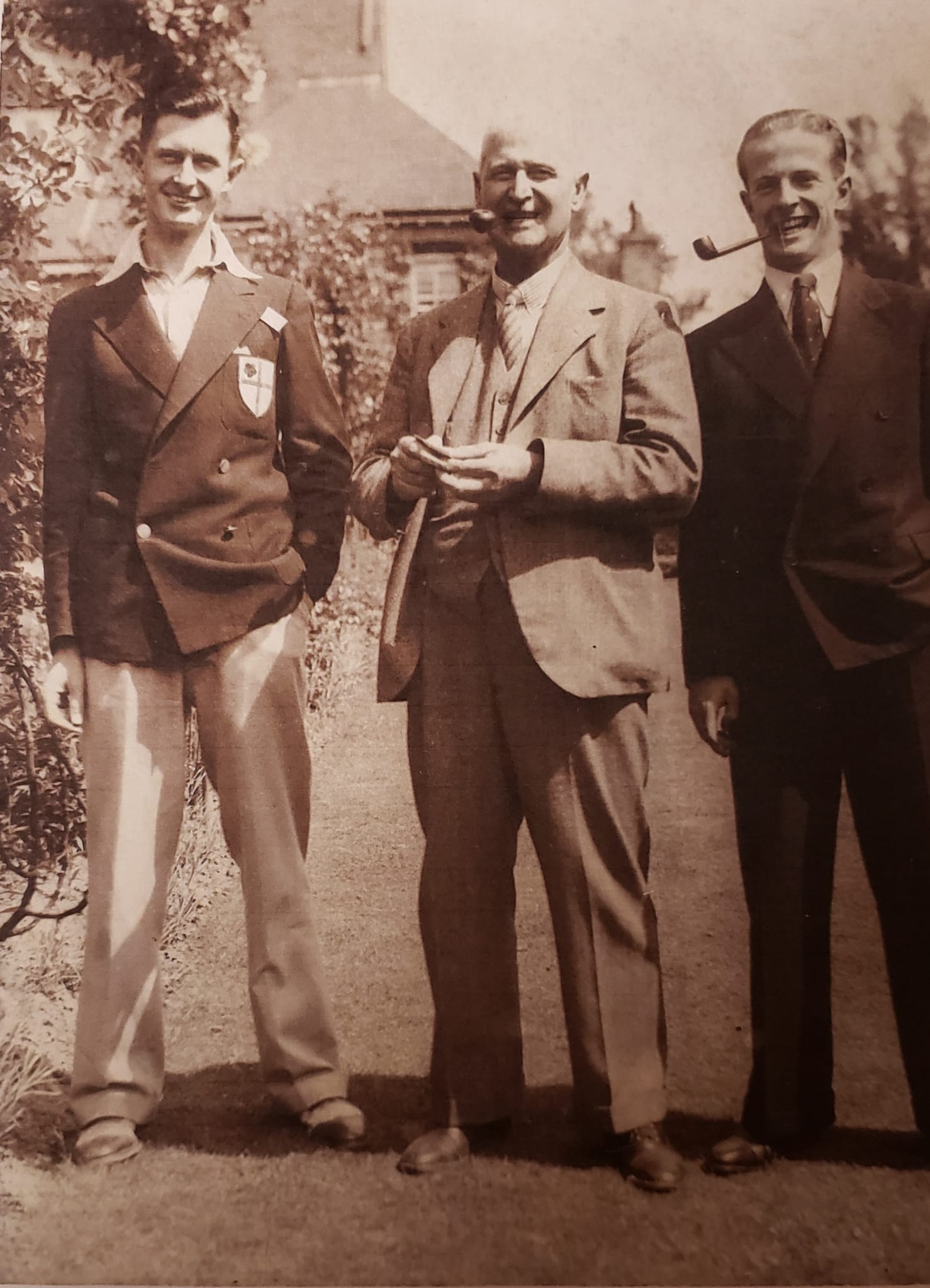

Main picture: HB Smith with Norman (left), and Matthew (right) at Bembridge, Isle of Wight c1937

Before my mother met my father, she had been married to an accountant by the name of Matson. His father had been a pilot on the Hugli River (one of the mouths of the Ganges near Calcutta in India) whose constantly-shifting sandbanks and channels required intimate knowledge of the local navigational problems. This seafaring propensity was destined to skip a generation, and so his grandson Aubrey Charles Matson probably had no idea of what was in store for him when his mother met and married my father in 1912. He was only seven years old, at a fairly adaptable age. His father had died tragically in a boating accident on the Boksburg Lake.

Aubrey was highly delighted when in 1918 his mother presented the family with my brother Matthew. He was equally pleased when I turned up in 1920. Not only was he enamoured of his baby brothers but we in turn grew to worship him. He was, I suppose, a bridge between babyhood and the pleasant but inscrutable world of the adults, being 12/14 years old. (Incidentally he was able, as a Boy Scout, to help during the great ‘flu epidemic of 1918).

I don’t know just when the sea-fever genes in his system began to germinate but, in the early ‘twenties he went off to complete his schooling in SATS General Botha in Cape Town. He was one of the first intake to that fledgeling (destined to become an august) establishment and enjoyed the rank of Cadet. His initiation was not entirely agreeable because at home he had been a slightly fussy eater. In the training ship, of course, meals had to conform to established standards. It was probably a case of “Eat it or go without”. At any rate, his appetite improved tremendously!

His first home leave was awaited eagerly by his young brothers and, no doubt, by Pop and mother. I don’t know how he arrived home at 18 Woodville Road but we were all at home. As he walked down the pathway, resplendent in his cadets navy-blue uniform with shiny brass buttons down the front and Naval cap perched jauntily on his head, Pop looked out from the front door and remarked “Good heavens, here comes Admiral Jellicoe!”.(That worthy sailor was one of the Royal Navy’s heroes of World War 1). The nickname stuck, and to his dying day we always knew him as Jellicoe.

I never thought of him as a half-brother, although that was obviously his legal status. His family status was always that of a warm and caring eldest brother. His training in General Botha completed, he served with shipping lines such as the P&O, Blue Star Line and Elder Dempster Line, obtaining his “first mate’s ticket”. He joined the South African Naval Service in the late ‘twenties as a Sub-Lieutenant (how proud we were to have a brother sporting even a humble single stripe on his sleeve!) and was very highly regarded by his Commanding Officer Tim Goddard. He was quickly promoted to Lieutenant – two stripes!

During this period in Cape Town he met and fell in love with Doris Chidley. Despite gloomy warning and pleas to mother by Goddard (“I’ve seen many a brilliant officer’s career ruined by marriage”) they were married in (I think) 1929. Shortly thereafter, Goddard’s predictions were justified. A General Election toppled the ruling United Party and the new Nationalist Party took control. It was decided that South Africa had little use for a Navy and the SANS would therefore be disbanded. No disaster so far, because Jellicoe was offered a transfer to the Royal Navy as a full Lieutenant. After due consideration they decided that they could not endure the separation involved in service in foreign parts, e.g. the China Station or Gibraltar. He therefore resigned his Commission and “swallowed the anchor“

Then followed a not unfamiliar pattern of events. Jellicoe had a severance “package” (in moderns terms) which enabled him to go into partnership with an individual who had a franchise to sell a carburetor improver for cars, in South-West Africa (now Namibia). He had no experience of the vagaries of commercial expertise. The venture failed and, his gratuity gone, he was only too glad to obtain employment in the service of the South African Railways & Harbours. His position was first mate on a hopper (a sort of seagoing wheelbarrow used to carry the sand scrapped up from the Durban harbour bed by dredgers and dump it out at sea). It was hardly commensurate with his status as a fully qualified ship’s officer and an ex-Naval one at that! But times were hard in the early ‘thirties and jobs were not easy to come by.

They lived in a cheap and basic Railways house at The Point in Durban (a not very upper-class area then, and later to become very sleazy). By now Doris was busy producing their son Beverly. How they managed on his salary of sixteen pounds a month I can’t imagine. She must have been a very competent housewife. Of course, in those days a pound went very much further than two rand does to-day but, still, it must have been a very bitter struggle.

Particularly so in view of the memory of his Navy days when money was no problem and all of his needs were met either by the Service or by his personal steward. During this period their second child, Fiona, was born. She was a delightful little girl who grew up to be an equally fascinating person and her horrible end in this last year of 1998 still haunts me. (She was butchered in her flat in Pinelands for no apparent reason other than sordid theft.)

Promotion was slow, but he progressed to first mate on a dredger, then captain, then first mate of a tug. By the time 1939 struck, he was captain of a tug. When World War 2 broke out on 3rd September of that year he immediately re-joined the South African Defence Force (as the Navy was now re-christened) with the rank of Lieutenant-Commander (two-and-a-half stripes!). He was given command of a minesweeper, HMSAS Southern Floe, and headed north for the Mediterranean in company with Southern Isles and Southern Seas. En route, he was transferred to the command of Southern Isles. Shortly afterwards, Southern Floe was torpedoed and sunk with heavy loss of life.

The rest of the little fleet reached the Mediterranean and did excellent service patrolling the approaches to ports such as Alexandria, Benghazi, Mersa Matruh, Derna, Sidi Barrani and Tobruk on the Libyan and Egyptian coasts. It was at this time that he caught up with his younger brother Matthew, now serving with the Royal Navy as a RNVR (South Africa) able seaman in HMS Gloucester. They met in Alexandria for a brief reunion before Gloucester was ordered to Crete to assist with the evacuation of Allied troops from beleaguered Greece. It was to be their last meeting- but that’s another story.

At Tobruk, Jellicoe was to sustain what he always described as his “inglorious wound”. It appears that he was commanding Southern Isles on patrol off the port when an enemy air-raid developed. A British destroyer steamed out of the harbour to engage the attacking aircraft and immediately attracted the attention of the unwelcome visitors. To his horror he saw one of a “stick” of bombs hit the stern of the ship, where the depth-charges were readied for submarine-hunting. The resulting spectacular blast, he realised, would reach his ship within seconds. His exposed position on the bridge was prejudicial to his continued health, but salvation was near- a steel “funk-hole” was built into a comer of the bridge. He dived for it a millisecond before the blast hit his ship. His aim was disturbed by the shock wave and, as he shot through the steel doorway, the side of his face connected with the frame. The resulting injuries put him out of action, eventually returning him to South Africa, where he was “grounded” to a shore job in Cape Town. In about 1947, Doris died.

Note on the author

Norman Smith was the son of Harold Bayldon Smith, the last owner of No. 7 Castle Castle Hill. Writing was clearly one of his skills. I have included the articles on Port Elizabeth under Port Elizabeth of Yore whereas those of a general interest have been published under Norman’s name. In about 1949 Norman Smith graduated from UCT as an electrical engineer and before his retirement he was the planning engineer for Port Elizabeth Electricity Department