I’ve heard of the word cenotaph and was aware that one existed at the corner of Rink Street and Park Drive. Apart from merely noting its presence whilst driving hither and thither to Varsity, I never pondered the meaning of the word. The odd ph letter grouping gives the hint that it has a Greek origin but that was about as far my thinking went. After all, there were far more important things to ponder as a young man. The truth is more revealing or shocking or startling, depending on how you look at it.

Main picture: Unveiling of the Cenotaph on the 10th November 1929

The word cenotaph is derived from the Greek kenos taphos, meaning “empty tomb.” In other words, it is a monument, sometimes in the form of a tomb, to a person or group of persons buried elsewhere or, in fact missing, presumed dead. The fields of Flanders in France might be strewn with military graveyards with their serried ranks of stark white crosses where politicians can pontificate every year about the iniquity of war whilst girding their (subjects’) loins for the next, but those were just the ones they could find. Probably more than 10% of those killed were just missing – either vaporized in an explosion or just subsumed into the mud that defined and epitomized the callous and careless butchery of WWI. For many it was not a case of dust-to-dust, but dust-to-mud.

I therefore think that the Cenotaph was an apt way of memorializing the dead and the missing that Port Elizabeth contributed to protecting the vainglory of the socio-political system that pertained in Europe and ultimately caused WWI. There, I’ve got all my deep leftie resentment off my chest. I can now continue with less emotional prose – or maybe not.

Thank goodness the ceremony was officiated by local dignitaries and not by the Butcher of Somme, Field Marshall Douglas Haig, as was the case for the Heavy Artillery Memorial. The ‘dunderhead’ had died the previous year to the relief of many and was hence unavailable to be the MC of the event.

The City Fathers/Mothers/Widows missed a huge trick. The war protagonists had signed a cessation of hostilities to commence on the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th Month of the 18th year of the 20th century. Numerologists would have been proud except for the last bit. In fact they would have further suggested, the 11th second of the 11th minute of the … . I don’t know the exact timing of the unveiling of the Cenotaph, but it was exactly 11 years later minus one day – damn! The 11th would have been a Monday so they wussed out to the Gods of Mammon and held it on the Sunday, the 10th.

Interpretation: How to Tame Your Dragon

The Cenotaph was conceived in a classical idiom. Given that St George is the patron saint of England and the St George’s Cross features in their flag, and given that the Memorial was placed directly outside St George’s Park, it is no coincidence that St George features strongly and so does his dragon. The following is culled directly from the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University site – http://www.stgeorgespark.nmmu.ac.za. Reader warning: you need to be tripping on a drug of your choice for it to make any sense:

The memorial was the work of James Gardner of the Art School and was erected by Pennachini Bros.

The general idea is that the lower portion represents the earthly life which uplifts gradually to a symbol of the heavenly life, which is the upper portion. The base has the shape of a sarcophagus around which runs a relief panel, having two side groups in the round.

Rising from the lower sarcophagus is a shaft which tapers and merges into a shape suggestive of an urn at the top, round which is a frieze of cherubs playing musical instruments.

Chastity is observed in the figures in the round and the relief panels. (Really! I wonder if there is an emoticon for that)

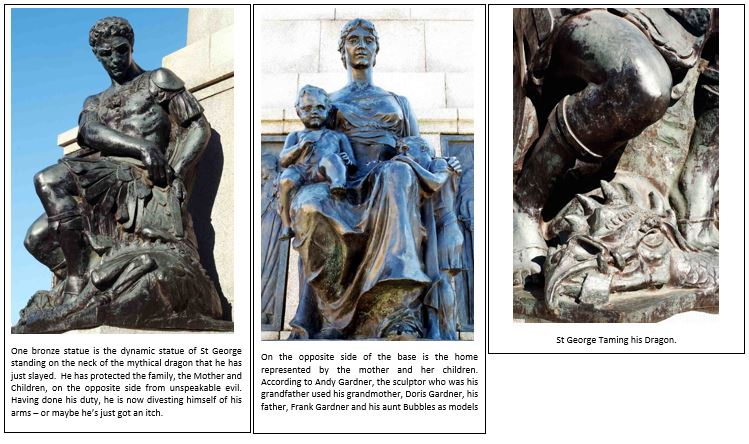

On two sides of the memorial are groups – one representing a mother and child and the other St George, placed so for the purpose of symmetry – that of the warrior’s wife symbolises the protecting of the home, and St George who has done his duty by crushing the evil threatened to our homes.

The mother is seated and has gathered the child in her arms for protection, whilst on her face the expression is of the calm, pure honesty of purpose of the whole of the British Empire. (Again, really?)

St George is unbuckling his belt and throwing off his accoutrements, having obtained his object(ive)s.

The relief panels are representative of the warrior starting out from civilian life and going through the various phases of the war – naval, military, nurses, etc. (and death as well)

The Memorial stands on a base of four steps, nine inches each in height and one foot six inches in tread. It is further heightened by a plinth one foot six inches in height and another nine inches in height. These serve as a platform for the religious services which are held at the Memorial from time to time.

Rising from this on two sides are panels for the names of the fallen and two bases for groups on the two other sides attached and in front of portions of the actual base of the Memorial. (Come again.)

A band of lettering of suitable wording binds the whole of the base together just below the sarcophagus, suggestive of the ties of the Empire. (OK, if you say so)

From the sarcophagus rises the shaft, pylon shaped, to the urn and culminating point of the memorial.

On two faces is carved a sword, the haft of which is encircled by a wreath. This is to suggest the crusade upon which the fighter went and returned victorious.

Having read that I realise why I was hopeless in poetry appreciation and interpretation classes and became an engineer. After rereading it a number of times, not taking any drugs and by studying the available photos intently, this is what I came up with.

To give the Memorial more gravitas (size and height) the designer, Gardner, started off with a circular base comprising a number of steps (4 steps of 9” to be precise). This formed the stage where dignitaries could be seen and heard. Rising from this was a single giant step of 18” so that wreaths can be propped up vertically against it during ceremonies. But Gardner obviously liked steps as he added one last one for luck. If this were a book we would just have finished the Preface, but in this case it is probably called a plinth.

Next comes the base which carries the names of the dead and the vaporized on panels on opposite sides and transverse to them we have outcrops for the two beautiful bronze statues. One is of St George after he has slayed the dragon and opposite is a mother and two children clinging to her who he has just protected. A band of words such as West Africa are picked out on the top course and run around the perimeter suggestive of the ties that bind the Empire (a bit of plagiarism there). We have now finished the Introduction and come to the business end.

Sitting on top of the base is the empty sarcophagus with a bronze relief panel embracing its perimeter. The panels represent all the aspects of the war starting with civilian life, the various arms of the Defence Force through to wounding and even death.

Rising from the sarcophagus is a tapered pillar signifying the ascent of souls of the dead to Heaven. Near the top, a band of cherubs merrily playing musical instruments are carved out of the granite and assist in making this process a jolly one – a kind of wake but without the alcohol. Being not well versed in the religious arts, I had to Google what a cherub actually was. It would seem that a cherub is one of the unearthly beings who directly attend to God according to Abrahamic religions – in other words we are talking about angels, but cute little ones.

Topping it all off is an urn. What its purpose is, I have no idea at all. At this point in your ascension from Earth to Heaven, you are less than fairy dust and have no use for an urn at all – at that stage, you ain’t got a pot to piss in.

World War II: Bring Out The Dead, Again

As if the world had not gorged itself enough, it was at it all over again 21 years later, and just like before the sons of Port Elizabeth sacrificed themselves again. This time they did not erect another memorial. They just added panels with names onto the neighbouring buildings.

And so the dead and the missing of two world wars were memorialised with this classical motif. But what about the lame, the halt and the insane – what of them?