A lasting legacy has been left by George Dix-Peek in his adopted town of Port Elizabeth in the form of some well-known buildings. Ironically his grandson, Milton Dix-Peek, also had ambitions of becoming an architect but WW2 intruded in his studies. Sadly, after the war he did not resume his studies.

Main picture: George Dix-Peek circa 1874 in colonial military attire

Joshua Peek was the father of no-less than ten children, one of which was George Dix Peek, who was to be progenitor and founder of the Dix-Peek clan of Southern Africa. Born at Hayes, Middlesex, England on the 8 July 1839, George was christened George Peek, and at some time during his youth took on the additional family name of Dix (documented in England as early as April 1861,as George Dix Peek), the surname of his great-grandmother Mary Dix, and his son Alban (my great-grandfather) was christened Alban Dix Peek (in Middlesex,1862). The “Dix” surname belonged to the “landed gentry” and originating in Norfolk. His father was a labourer and the descendant of a family resident in the Isleworth area of Middlesex since at least the 17th century.

Educated in Uxbridge, he married his life-partner, Frances Turton, on the 15 April 1861, in the district of Wycombe, Buckinghamshire, where he was apparently resident at the time, and in employ as a Schoolmaster.

Frances Turton [1841-1927], was born at Cowley, Middlesex, on the 22 November 1841, and at the time of her marriage to George, was resident at North Hyde, Heston, Middlesex, the daughter of James Turton, a grocer, originally from Hampshire, and Elizabeth Money.

Prior to emigrating to the Cape Colony, Frances gave birth to three boys, one of which, Harold George Peek, was to remain in England with his grandparents, who were “Plymouth brethren”, while the other two, a toddler and infant respectively, accompanied their parents to “Darkest Africa”. George and Frances’ first-born, and my great-grandfather, Alban Peek, were roughly two-years of age at the time of their departure.

Arrival in South Africa

The family arrived at the Cape between May 1864 and November 1865, George acting in the capacity of consulting engineer to a group of settlers tasked with the erection of a town outside Cape Town, which was to be named Bridgetown.

The enterprise was led by a certain Sackett, who was apparently non compos mentis. While at Bridgetown, the first of the progeny to be born on South African soil, Henry MacDonald Peek first saw the light of day. George grew wary of the whole ordeal, and as was typical of George, decided together with another member of the party, to walk the one hundred miles to Cape Town, and seek better employment of his skills.

He was able to find gainful employment as a teacher at the native college at Zonnebloem, where he instructed the sons of African chiefs, and was employed thus until he and his little band removed in 1868, to a small settlement named Port Elizabeth, situated in the eastern cape region of South Africa.

Their litter now comprised four sons, the most recent being Arthur Balfour Turton, who was born to George and Frances while the family was at Zonnebloem. Thus began their life in the town that was destined to become the ancestral home of the Dix-Peek’s of southern Africa.

Their initial period of residence in Port Elizabeth seems to have seen both George and Frances employed in the pedagogic arts. Frances, who in July 1869, was reported on the verge of opening a girl’s school, in Queen Street, near St. Pauls’ church, on the 2 August that year, while George was temporarily engaged in giving Drawing lessons at the commercial school, while awaiting the imminent arrival of an accomplished school mistress from England.

George had already embarked upon his vocation as an architect, having opened an architectural Practice in Port Elizabeth in 1868, which was to last well into the 1890s – a period of almost thirty years. His practice was so successful, that he had to take on a partner, namely W.H. Miles, in 1880. The firm, “G. Dix Peek and W.H. Miles'” received the tender for the construction of the Feather Market Hall, an aesthetically-pleasing edifice, which still stands today. George was so busy at the time that Miles was tasked with the construction of the Feather Market Hall, all the plans being attributed to Miles.

The partnership, however, was doomed to failure, and terminated in 1881. The dissolution of the partnership was advertised on the front page of the Eastern Province Herald in March 1881, whereupon one of his sons, namely St. George, Dix Peek, joined the business, and it thus became a family business – Dix -Peek and Son. George designed many buildings in Port Elizabeth.

They include the Standard Bank, also known as the “Bank with the Bulge” (1874); St Patrick’s Hall, in Queen Street (which was at the time described as the “largest hall in the Cape Colony”; Armstrong Auction Room (1879), which stood on the corner of Donkin Street; Lombard Chambers (1879); the Albany Hotel, in Jetty street (1881); Polliack’s building, in Main Street, which is now Govan Mbeki Avenue and the Edward Memorial Church, in Edward street, Central, which belonged to the London Missionary Society (LMS), but was later altered when purchased by the Dutch Reformed Church, and was still in existence in 1987; and the school buildings of the Dominican Convent . His work also includes alterations and refurbishment of various other Port Elizabeth landmarks, such as the “Palmerston Hotel” (alterations done in 1878); No 28 Bird Street, Central; and the Prince Alfred’s Guards Museum. George was by all accounts a difficult person; Eccentric, but not insane.

A perfectionist, George was often in conflict with others due to his meticulous attention to detail, a notable incident being during the construction of Edward Memorial Church. A contractor, surnamed White, was ordered by George to demolish parts of the church because apparently the quality of sand was poor, and obviously not up to George’s standards. White refused to do thus, whereupon, George then took it upon himself to demolish the aforesaid parts, and personally supervised the rebuilding thereof.

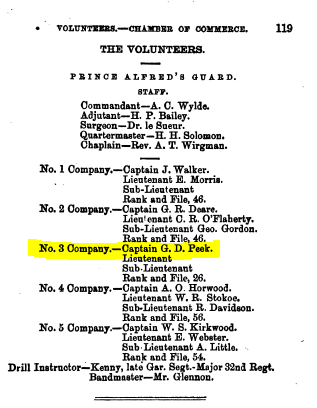

George’s abiding love, however, was the military, and he was commissioned a Captain, in 1874, in a famous Port Elizabeth militia regiment, The Prince Alfred’s Guard (PAG). The actual parade for the newly-commissioned officers and the rank and file, took place on Saturday, the 11 July 1874, and was inspected by Lieutenant- General Sir Arthur Cunynghame, who had arrived in South Africa in 1873, as Commander-in-Chief, and who officially conferred upon the unit the distinguished title of Prince Alfred’s Guard. George was described in contemporary reports as a “picturesque figure of military bearing who wore a puggree of puce-coloured silk round a white military helmet, with the ends hanging down to protect his neck.” George was also to form the “Port Elizabeth Militia” Regiment, which served under his command in the Transkei, during the Ninth Frontier war (1877-1878).

This regiment comprised two companies, numbering approximately 50 men, and was clad in brown velvet cord, with short leggings, and topped off with a soft black hat, turned up on the one side, the upturned end surmounted by a red feather. His eldest son, Alban, only fifteen-years-of-age at the time, served under his father in No 1 Company, ostensibly filling the role as Bugler.

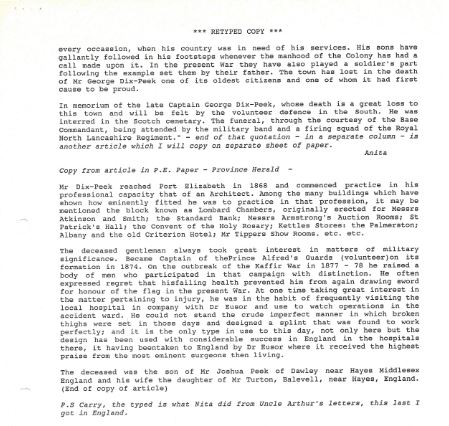

A multifaceted man, George was also an inventor, and designed a new direct extension splint for simple and compound fractures of the femur. The splint was first advertised in 1876, and was apparently utilized by doctors overseas. George passed away on the 22 May 1901, just short of his sixty-second birthday. He was the oldest architect in Port Elizabeth at the time of his death.

A contemporary obituary notice described him thus: “At one time and before his health began to fail, Mr. Dix-Peek was, if not a celebrity, a prominent and useful member of society.”

This indomitable man from Hayes, Middlesex, the son of a labourer, was laid to rest in May 1901, at the Scotch Cemetery (now interestingly enough named, St. George’s Park), together with one of his son’s, Henry MacDonald Dix-Peek, who predeceased him, and passed away in 1900, and was honoured by a contingent of the Loyal North Lancashire Regiment – a fitting tribute to a man of martial spirit. Of humble origin, George had truly created a legacy, and at the time of his death was pecuniarily blessed, the family living well.

Fortunately though, George was not alive to hear of the death of his son, Sergeant Douglas Dix Peek, just two months later, on the 13 August 1901, the result of “Felo de Se”, as all the money in the world would not have been able to assuage his abject sadness, and a parent’s unbridled dread of outliving one’s offspring! His beloved wife, Frances, was to outlive him by many years, succumbing in Durban, South Africa, in approximately 1927, being then in her eighty-sixth year!

Family Pets

A word or two about George’s animals and pets. He owned a grey parrot that used to climb onto George’s bed and call, “Coffee George”, whereupon coffee would be brought in for both George and Frances. Sadly, upon George taking his regiment, the Port Elizabeth Militia off to war in 1878 during the Ninth Frontier War, the grey parrot subsequently pined for his master and was dead within three days of George having left. In addition the family also possessed a dark grey stallion named “Diamond” (which belonged to Frances, who was, apparently, a fine horsewoman), and a Shetland mare, and her little grey foal, “Dixie”.

Military Affiliations

George Dix-Peek served in the Prince Alfred’s Guard, a famous Port Elizabeth and South African volunteer regiment, being commissioned a captain in July 1874, and during the Ninth Frontier War (1877-1878) he raised and led a unit called the Port Elizabeth Militia, the details of which are mentioned earlier, and was accompanied by his 15 year-old-son, Alban, who served ostensibly as the unit’s bugler in No 1 Company, but was really there to keep his father company. He and his unit left Port Elizabeth for the Transkei aboard the coastal steamer “Florence”, bound initially for East London in the Eastern Cape, whereupon they then marched to the theatre of hostilities. The war was waged against the Gcaleka’s and the Gaika’s, and George Dix-Peek’s unit apparently served with distinction.

George related in a letter to his son Arthur in which he wrote: “I wrote a long letter to your dear Mama yesterday. I expect to return to her on the 13th June, or rather to march from here on that date through some 100 miles of enemy territory and then some 350 miles further to Port Elizabeth. After remaining at home for about two weeks I expect to return to the war with about 100 fresh men. If you could be here this evening and look out on the quiet scene you would find it hard to think that the enemy was prowling about in such a place, and carefully watching an opportunity to attack. Large numbers have been killed during the last month but more tribes are still rising and joining those already in arms. One can only wonder at their foolishness as they only draw down the most terrible suffering upon themselves.”

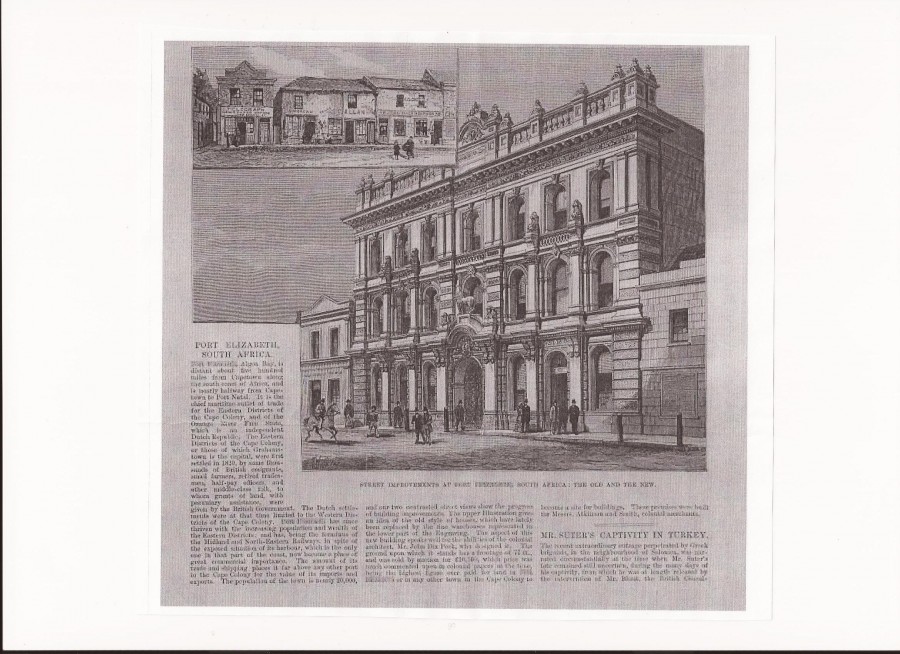

Excerpt from the Illustrated London News, September 1881

“Port Elizabeth, South Africa,

Port Elizabeth, Algoa Bay, is distant about five hundred miles from Capetown along the south coast of Africa, and is nearly halfway from Capetown to Port Natal. It is the chief maritime outlet of trade for the Eastern Districts of the Cape Colony, and of the Orange River Free State, which is an independent Dutch Republic. The Eastern Districts of the Cape Colony, or those of which Grahamstown is the capital, were first settled in 1820, by some thousands of British emigrants, small farmers, retired tradesman, half-pay officers, and other middle-class folk, to whom grants of land, with pecuniary assistance, were given by the British Government. The Dutch Settlements were at that time limited to the Western Districts of the Cape Colony. Port Elizabeth has since thriven with the increasing population and wealth of the Eastern Districts; and has, being the terminus of the Midland and North-Eastern Railways, in spite of the exposed situation of its harbour, which is the only one in that part of the coast, now become a place of great commercial importance.

The amount of its trade and shipping places it far above any other port in the Cape Colony for the value of its imports and exports. The population of the town is nearly 20, 000, and our two contrasted street views show the progress of building improvements. The upper illustration gives an idea of the old style of houses [inset], which have lately been replaced by the fine warehouses, represented in the lower part of the engraving. The aspect of this new building [The Standard Bank] speaks well for the abilities of the colonial architect, Mr. George Dix Peek, who designed it [in 1874]. The ground upon which it stands has a frontage of 77 ft., and was sold by auction for £10, 100, which price was much commented upon in colonial papers at the time, being the highest figure ever paid for in land in Port Elizabeth, or in any other town in the Cape Colony to become a site for buildings. These premises were built for Messrs. Atkinson and Smith, colonial merchants.”

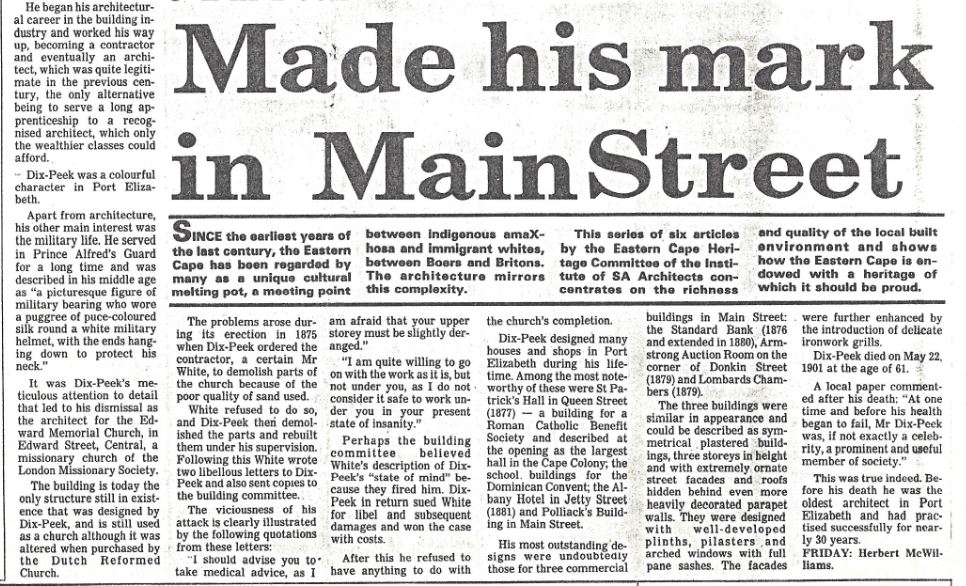

Excerpt from the Eastern Province Herald dated 8th June 1987

J (sic) Dix-Peek – Port Elizabeth’s first architect by Albrecht Herholdt

Peek, who later in his life adopted the double-barrelled name Dix-Peek was born in 1839.

He began his architectural career in the building industry and worked his way up, becoming a contractor and eventually an architect, which was quite legitimate in the previous century, the only alternative being to serve a long apprenticeship to a recognised architect which only the wealthier classes could afford.

Dix-Peek was a colourful character in Port Elizabeth.

Apart from architecture, his other main interest was the military life. He served in Prince Alfred’s Guards for a long time and was described in his middle age as “a picturesque figure of military bearing who wore a puggree of puce-coloured silk round a white military helmet, with the ends hanging down to protect his neck.”

It was Dix-Peek’s meticulous attention to detail that led to his dismissal as the architect for the Edward Memorial Church in Edward Street, Central, a missionary church of the London Missionary Society.

The building is today the only structure still in existence that was designed by Dix-Peek, and is still used as a church although it was altered when purchased by the Dutch Reformed Church. A problem arose during its erection in 1875 when Dix-Peek ordered the contractor, a certain Mr White, to demolish parts of the church because of the poor quality of sand used.

White refused to do so and Dix-Peek then demolished the parts and rebuilt them under his supervision. Following this, White wrote two libellous letters to Dix-Peek and also sent copies to the building committee.

The viciousness of his attack is clearly illustrated by the following quotations from these letters: “I should advise you to take medical advice, as I am afraid of that your upper storey must be slightly deranged.” “I am quite willing to go on with the work as it is, but not under you, as I do not consider it safe to work under you in your present state of insanity.” Perhaps the building committee believed White’s description of Dix-Peek’s “state of mind” because they fired him. Dix-Peek in turn sued White for libel and subsequent damages and won the case with costs. After that he refused to have anything to do with the church’s completion.

Dix-Peek designed many houses and shops in Port Elizabeth during his lifetime. Among the most noteworthy of these were St Patrick’s Hall in Queen Street (1877) – a building for a Roman Catholic Benefit Society and described at the opening as the largest hall in the Cape Colony, the school buildings for the Dominican Convent; Albany Hotel in Jetty Street (1881) and Polliack’s Building in Main Street.

His most outstanding designs were undoubtedly those for three commercial buildings in Main Street: the Standard Bank (1876 and extended in 1880), Armstrong Auction Room on the corner of Donkin Street (1879) and Lombard’s Chambers (1879).

The three buildings were similar in appearance and could be described as symmetrical plastered buildings, three storeys in height and with extremely ornate street facades and roofs hidden behind even more heavily decorated parapet walls. They were designed with well-developed plinths, pilasters and arched windows with fill pane sashes. The facades were further enhanced by the introduction of delicate ironwork grills.

Dix-Peek died on May 22, 1901 at the age of 61. A local paper commented after his death: “At one time and before his health began to fail, Mt Dix-Peek was, if not exactly a celebrity, a prominent and useful member of society. This was true indeed. Before his death, he was the oldest architect in Port Elizabeth and had practiced successfully for nearly 30 years.

Sources:

Magazine: Looking Back dated March 1992: Pages 36-42

Newspapers: The Eastern Province Herald dated 8th June 1987

Books:

Margaret Harradine: A Social Chronicle of Port Elizabeth to the end of 1945

General Dir of SA 1898-99

Oberholster, PBD suppl Sep/Oct 1982: 1-7

Internet:

Notes Pertaining to the Dix-Peek Family of England and Southern Africa (c.1268-2011) by

Ross Dix-Peek: http://peek-01.livejournal.com/45032.html

George Dix Peek (1839-1901): A Port Elizabeth Architect: http://peek-01.livejournal.com/81873.html

Memories of his son recalled in 1931:

Dix-Peek designed many houses and shops in Port Elizabeth during his lifetime. Among the most noteworthy of these were St Patrick’s Hall in Queen Street (1877) – a building for a Roman Catholic Benefit Society and described at the opening as the largest hall in the Cape Colony, the school buildings for the Dominican Convent; Albany Hotel in Jetty Street (1881) and Polliack’s Building in Main Street.

His most outstanding designs were undoubtedly those for three commercial buildings in Main Street: the Standard Bank (1876 and extended in 1880), Armstrong Auction Room on the corner of Donkin Street (1879) and Lombard’s Chambers (1879).

The three buildings were similar in appearance and could be described as symmetrical plastered buildings, three storeys in height and with extremely ornate street facades and roofs hidden behind even more heavily decorated parapet walls. They were designed with well-developed plinths, pilasters and arched windows with fill pane sashes. The facades were further enhanced by the introduction of delicate ironwork grills.

Dix-Peek died on May 22, 1901 at the age of 61.

A local paper commented after his death: “At one time and before his health began to fail, Mt Dix-Peek was, if not exactly a celebrity, a prominent and useful member of society.

This was true indeed. Before his death, he was the oldest architect in Port Elizabeth and had practiced successfully for nearly 30 years.