In a large measure, the lack of a proper water borne sewerage system symbolised the lack of development in Port Elizabeth as compared with the home country where John Snow had proved that a proper sewerage system was vital from a hygiene perspective especially the prevention of cholera.

This blog covers the development of a proper sanitation system in Port Elizabeth.

Main picture: Sewer being constructed in Rudolph Street South End in 1904.

Early solutions

Needless to say, sanitation is not an issue which the general reader finds interesting. As a consequence, little is written about it. Even the comprehensive Social Chronicle has sparse comments on the topic. Yet imagine a world without water borne sewerage or even the unhygienic conditions of the “involuntary” Jewish passengers locked into cattle trucks for their week long journey to the extermination camps!

For the first sixty to seventy years after 1820, no formal sewerage system had yet been developed. JJ Redgrave in this book, Port Elizabeth in Bygone Days, provides a peak into this unknown world where backyards, alleyways and gutters became the recipients of the slops and dirty water of all forms.

Apart from the water supply, what to do with the town’s sewerage was the most serious problem that faced the municipality over the years. After abandoning the very early arrangement of depositing the unsavoury contents of buckets on the beach below the high-water mark, the bucket system was introduced, with variations in the manner of organisation as time passed. The service lanes which still exist in the older parts of the City are a reminder of the outside toilet and its bucket. Some residents even dug pit latrines into their gardens.

Status of sanitation in 1899

The annual mayor’s report dated 31st December 1899 recognises that the sanitary system in the town was “unsatisfactory”. Furthermore, it states that “The rate of mortality is great.” One presumes that this comment refers to the rate of typhoid infection as a consequence of poor sanitation and poor sewerage systems.

According to David Raymer in his book Streams of Life, “At this time the town’s sanitary services consisted of a once-weekly bucket removal system or pit latrines, and during 1899 approximately 175 000 individual removals were carried out. What drainage existed during this period consisted of a number of fairly large stormwater culverts, the bottoms of which were stone paved, discharging into the Baakens River, the area which is now the harbour, and at other points into the sea. Council permission could apparently be obtained to connect domestic waste water, but not sewage, into these culverts. This drainage system existed from 1899 to 1916.”

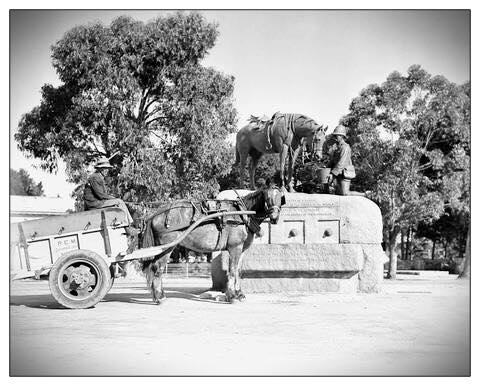

Service lanes by Henie Grevenstein

These narrow alleyways serve one very important function. They are a discreet means for nightsoil workers with horse drawn carts to move along these alleyways and collect human excrement through small door openings from outdoor latrines, which bordered the lane. Many homes still have remnants of the outdoor loo’s bordering the service lanes. This must have been classified as the worse job ever. By 1899, 3365 buckets were collected once a week and the collection discarded into the Baakens river. It was not until 1916 that a proposed gravity feed system was introduced.

By searching on Google Earth and plotting out the locations of the service lanes one can almost draw a boundary of homes using buckets systems prior to 1916. One can also see how urban development first progressed along major roads and then after filled up areas further away from the roads.

Naturally horses for night soil carts had to be housed somewhere. Behind Masterson’s Coffee Shop in Russell Road, horse stables were provided. Outlines of the stable doors can still be traced on building wall facing Parliament Street. There used to be a wooden post in Parliament Street where horses could be tethered to.

Installation of water born sewerage system

In 1904 the first comprehensive sewerage scheme for the entire town was prepared by the Town Engineer, Arthur Butterworth. The scheme as costed amounted to £400 000 but the Council baulked and requested that a second opinion be obtained. As requested a consulting engineer, Mr. Midgley Taylor, was commissioned. Being British, Taylor had to come out from Britain. He investigated what was required and ultimately submitted an estimate £50,000 less than Butterworth’s calculation.

In terms of the Council’s mandate, all such expenditure had to be approved by the ratepayers. It was only during 1906 that this plan was presented at a meeting of ratepayers. Probably fearing increased rates, the meeting only approved an amount of £200,000.

Refuse removal

In all probability this rubbish truck could only hold 10 cubic metres of rubbish. In the 1960s, the McCleland household at 57 Mowbray Street generated less than a quarter cubic metre of rubbish per week whereas today we generate one cubic metre per week. The offending items can be categorise as one-use items such as cooldrink bottles whereas in the past this was mainly organic material such as peels and skins

The answer was inadvertently provided by Rupert Mouat in his memoirs when he described the shopping and food preparation process as follows:

Dee always made leavened brown bread, and I would walk or cycle three times a week from Cape Road to fetch our loaves. In those days the butcher, the baker and the grocer called daily for orders and Moms bought small white cottage loaves joined in pairs The milkman arrived with a huge churn on a horse-drawn float and used assized beakers to measure the milk into our jugs. Mrs Brookes across the road poured a full pint of milk through ·a muslin bag every day to make delicious cream cheese.

A Chinaman carried fresh fish on each end of a split bamboo pole and charged 1/- for a pair of red romans which he cleaned free in our backyard. Hawkers sold peaches, apricots and plums 80-100 for one shilling and a bushel basket of pineapples sometimes cost only 9d.

This is illustrative. but what Mouat does not make explicit is that no containers were disposable. In the purchasing process, reusable containers were utilised In the food preparation process, all skins and peals were composted on the property. In turn the compost was utilised on their vegetable patch.

Further attempts were made to have the full scheme passed by the ratepayers, but it was not until 1913 that the whole sewerage scheme, as originally envisaged by the Town Engineer and the consulting engineer, was finally approved and submitted to the Provincial Administration.

These consultative meetings attracted a large audience and at one such meeting no less than 1 400 ratepayers attended. As inflation had taken it toll, the final amount of the scheme as approved now amounted to £500 600.

It was not until 1916, some twelve years after the preparation of the first sewerage scheme, that actual construction commenced and even then, the Council still had a further obstacle to overcome. The New Brighton Land Company was aggrieved that the proposed sewer outfall was adjacent to their property. In light of this, they made an application for an interdict to restrain the Council from constructing the proposed sewer outfall. Fortunately, the Council successfully opposed this application. A loss in this matter would once again have delayed implementation.

Having cleared all obstacles, the sewerage scheme progressed rapidly after 1916, and by 1922 the whole of the gravity section from the Baakens River to the sea outfall had been completed.

Extensions

In principle, the project now became one of extending the reticulation system to the whole of the municipal area. As Raymer states, “Between 1923 and 1930 the sewerage reticulation system was extended in the direction of Humewood and the Hill area as far as Mill Park and many parts of North End were drained. In 1931 the Whites Road and Military Road drainage, which for about 40 years had been connected into the stormwater system, and had discharged onto the foreshore near the North Jetty, was diverted into the Main Town Intercepting Sewer in Baakens Street. The following years saw a further rapid expansion in the sewerage system, encompassing such areas as South End, Westview, Summerstrand, Korsten, Kensington, New Brighton, McNamee Village and Schauder and Mount Road Townships. In 1938 a start was made in the construction of the Papenkuils Valley Main Sewer, thus opening up areas situated in the north west of the City.

With the outbreak of war in 1939, the Sewerage Division ceased to work as a separate entity and was temporarily absorbed into the Waterworks Section. As a result, no major sewerage schemes were undertaken between 1940 and 1945. This period was devoted to the carrying out of sewerage reticulation schemes in Sidwell, MacNamee Village and New Brighton. It was a difficult period for the department as so many staff members had enlisted for the war.

In 1946 the main Town Intercepting Sewer gave indications of becoming surcharged between Albany Road and the sea outfall. To relieve this condition, a new high-level interceptor was constructed during 1947, commencing at the top of Albany Road and passing through Mount Road Township, Kensington and finally connecting into the sea outfall. At approximately the same time, additional staff from overseas were engaged in the Sewerage Division and the tempo of work was increased.

Between 1946 and 1950, sewerage reticulation schemes were installed in Neave Township, Perridgevale, Newton Park, Glendinningvale, Millar Grange, Mount Road Township, North Downs, Southdene, Ferguson Township and Forest Hill.

1951 and 1953 saw the commencement of the Deal Party Trunk Sewer and the Humewood/Summerstrand main sewer, together with the development of sewerage reticulation in Parsons Hill and Adcockvale. In 1953 a start was made on the Northern Intercepting Sewer in Grahamstown Road, to serve what is now the Site-and-Service (Kwazakele) area. During this same ear, Deal Party Industrial Area No. 2 was sewered, as was Glen Hurd Township. During the early 1960’s the sewerage system of the City was again greatly extended; areas such as Newton Park Area 8, Fern Glen Extension No. 1, Cotswold, Linton Grange, Westering, Kabega Park, Humewood Extension 1, Summerstrand Extension 3 and Framesby Township were included. In addition, during this period Elundini, Gelvandale and Schauder Township were completely sewered and further portions of Korsten and Kwazakele were drained.

Up to 1966, Port Elizabeth had approximately 371 miles of sewers and 20 sewage pumping stations under maintenance.

Sewage reclamation works

Finally, reference must be made to the sewage reclamation works. Under the old system of disposing of raw sewage and crude industrial effluent into the sea, pollution problems were being experienced along the city’s beaches. With the establishment of the Cape Receife Wastewater Works in 1972; Fishwater Flats Wastewater Works in 1976 and Driftsands Wastewater Works in 1987, these problems were overcome, thus making it possible to develop all beaches fully. Furthermore, it became possible to produce reclaimed water for industrial and irrigation purposes. All these works have been expanded as the sewage demand increased and refurbished as the equipment became redundant. City Engineer, Doug MacCallum, had the foresight to separate the residential and industrial processes at the Fishwater Flats Wastewater Works. This has made recycling of the domestic effluent more attractive as heavy metals from industry are not present.

Sources

Port Elizabeth in Bygone Days by J.J. Redgrave (1947, Rustica Press)

Streams of Life: The Water Supply of Port Elizabeth and Uitenhage by David Raymer (October 2008, Express Litho Services, Port Elizabeth)