WW2 was fought across the oceans of the world. As such the seas off Port Elizabeth were not immune from the depredations of the scourge of the seas: The U-Boat. One such vessel that was sunk off the Eastern Cape coast was the Liberty Ship, the Anne Hutchinson.

The American Liberty ship Anne Hutchinson SS was torpedoed and shelled on October 26th, 1942, by German submarine U-504. Her stern portion up to No. 4 hatch was blown off. The forepart was towed into Algoa Bay on October 31st. Three lives were lost.

Main picture: Anne Hutchinson after being torpedoed

Details of Attack

At 18.43 hours on 26 Oct 1942 the unescorted Anne Hutchinson (Master John Wilhelm Stenlund) was hit on the starboard side by two of four torpedoes from U-504 about 60 miles east of East London, South Africa. The U-boat had missed the ship five minutes earlier with a spread of two stern torpedoes because she just did a turn to starboard on her zigzag course after the torpedoes were fired. Lookouts then spotted one torpedo of the second spread to pass 20 yards ahead of the vessel, but it was too late to take avoiding action and two torpedoes struck abaft the engine room in the #4 hold almost simultaneously. The explosions buckled the side of the ship, created a hole 14 feet by 16 feet, broke the propeller shaft, stopped the engines, knocked out the electrical systems, smashed the wireless set and blew the #4 hatch covers off, killing three men sitting on them. An oil tank had also been holed, covering the after gun and its crew with oil. However, the bulkheads on either side of the hold remained intact but as the ship was completely disabled the surviving eight officers and 29 crewmen abandoned ship in three lifeboats, followed shortly thereafter by the 17 armed guards (the ship was armed with one 4in, four 20mm and two .30cal guns) in the fourth. At 19.28 hours, a coup de grâce struck the fire room, causing the boilers to explode. The U-boat then surfaced and left the area without questioning the survivors because search lights were seen nearby, the ship was judged beyond salvage and the Germans had to reload the torpedoes from the upper deck containers.

About 90 minutes after abandoning ship, the lifeboats set sail towards the coast, but one got separated and its 10 occupants were picked up six hours after the attack by the American steam merchant Steel Mariner and landed in Durban on 28 October. On the night of 27 October, the remaining survivors were picked up a fishing vessel off Port Alfred and landed there at dawn the next morning. Two of the survivors had to be treated for minor injuries and the 44 men were later taken to Port Elizabeth. The Anne Hutchinson stayed afloat and on 29 October, the South African armed trawler HMSAS David Haigh (T 13) and a harbour tug attempted to tow the ship to port but were not powerful enough. Dynamite charges were placed aft under the ship, cutting her in two. The after section sank and the fore section was towed to Port Elizabeth by the armed trawler, arriving there on 1 November, but was declared a total loss. A boarding party also recovered the confidential papers that had been left behind by the master, who was criticized for this breach of the Admiralty regulations.

What happened to the bow?

As the ship was torn asunder by the impact of the torpedoes which had struck amid ships, the stern half of the ship sank but the bow remained afloat. It then proceeded to steadily drift along the coast past Port Elizabeth. The tug, the John Dock, was despatched to tow the remaining portion of the ship to Port Elizabeth where it would be assessed. Aboard the tug were Mr C.F. S. van der Merwe, another deckhand Dick Campbell and Captain John Stockley.

The John Dock had been warned not to go too near the Anne Hutchinson as aircraft covering the operation had spotted submarines lurking in the area. Apparently according to an article in the E.P. Herald in 1960 entitled, “They saw ship’s better half”, the ship had drifted down to Plettenberg Bay. Apparently due to heavy seas, it was only on the following day that the master and two deckhands succeeded in securing a heaving line to the bow portion. By that time, assistance had arrived in the form of a South African naval minesweeper, the David Haigh. According to the book War in the Southern Oceans, the captain of the David Haigh, Lt H.F. van Eyssen, was awarded the MBE for his handling of the affair.

In the EP Herald article, my aunt, Kathleen Wood, recalled how her husband, George, was involved in the rescue of the crew. At that stage, George Wood was a branch manager of shipping agents for Robin Lines . As such, the Anne Hutchinson formed part of Robin Line’s wartime fleet. Mr Wood received a phone call from Port Alfred where the master of the Anne Hutchinson together with a group of officers and men had landed in a lifeboat. Apparently they were overjoyed when they saw that they were near to an inhabited place and were able to sail straight up the Kowie River. Mr Wood immediately drove up to Port Alfred and brought Captain John Stenlund and some of the crew back to town.

Mrs Kathleen Wood recalled that her husband took Captain Stenland, who was also a great family friend, for a drive down the coast towards Schoenmakerskop. The captain spotted an object on the horizon and suddenly realised that it was the remaining half of his ship. It was drifting down the coast on the current and Stenland was anxious as the bow presented a great hazard to shipping since there were no lights on board.

Stenland then remarked that “Poor Anne Hurchinson. She was burned at the stakes and now she has been blown in two.” The reference to “burning at the stakes” relates to Ann Hutchinson after whom the vessel was named. She was a Puritan spiritual advisor, religious reformer, and an important participant in the Antinomian Controversy which shook the infant Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1636 to 1638.

Incidently, George Wood had a passion for ships and was affectionately known as the “walking encylopedia in shipping”. His hobby was taking photos of ships and wrecks along the coast.

The reason why the remaining portion of the Ann Hutchinson had managed to remain afloat after being sliced into two was that airtight compartments had been built in the centre of the ship. It was this that had kept her afloat. As the condition of the vessel first had to be ascertained, it was not towed into the harbour but instead anchored off the Sunday’s River mouth. Upon inspection she was found to still be seaworthy and then towed closer to the harbour and ultimately into the harbour where salvage work could commence. In PE harbour she was stripped of all her instruments, engine parts, plates and anything else of value. These were later shipped back to the United States.

Ultimately her end came in a most ignominious manner. The Anne Hitchinsion was finally towed into the Bay and used for target practice by the Humewood Battery of the S.A. Coastal Artillery. Guns fired from this battery finally put the last remnants of the Anne Hutchinson to rest at the bottom of Algoa Bay.

Details of the Anne Hutchinson

Article by Rosemary MacGeoghan

Rosemary is the daughter of George Wood and my cousin

Soon after midnight on Wednesday morning, 28 October 1942, George Wood, Branch Manager of Mitchell Gotts, Port Elizabeth, received a telephone call from Port Alfred, notifying him of the arrival of survivors from a stricken ship. They asked if he could please come and make arrangements for the men and to please bring a doctor, as there were some injuries among the men. They told George Wood that lifeboats from the Anne Hutchinson had arrived earlier on at the village of Port Alfred, after sailing up the river.

After ascertaining that it was the Liberty ship, the Anne Hutchison and part of the Robin Line War-time Fleet, George Wood immediately picked up Dr Fred Morrison and the Mitchell Gotts’ Senior Clerk, a Mr. Fred Wilson. They left Port Elizabeth on the Grahamstown Road and at the Nanaga intersection turned off onto a red, dusty road to Alexandria/Port Alfred. George Wood was very grateful to have had Fred Wilson with him as they encountered many farm gates along the way to the Kowie.

Rosemary MacGeoghegan was recently informed by the well-known Bill Deacon, of Bushman’s River Mouth, that in 1942 there had been 27 gates between Nanaga and Alexandria, but he couldn’t remember the number between Alexandria and Port Alfred as it was not a well-used road in those days, as it was too far away.

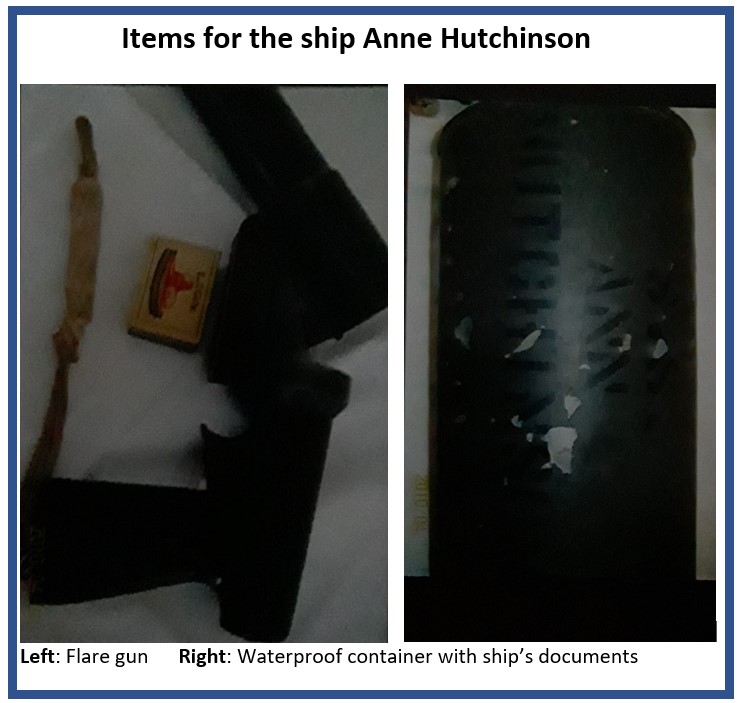

On their arrival in Port Alfred, George Wood met up with Captain John Stenlund and his Chief Engineer (possibly a Mr. Price), while Dr Morrison attended to the injured seamen, one with severe head injuries. Fred Wilson made arrangements to have the seamen transported to Port Elizabeth by train. Captain Stenlund had in his possession a waterproof metal cylinder, with the name SS Anne Hutchinson stenciled on it, containing certain of his ship’s documents that he had brought off the ship during the evacuation. George Wood brought Captain Stenlund, the Chief Engineer and the metal container back to Port Elizabeth. George Wood booked them both in at the Palmerston Hotel while his crew was sent to the Seaman’s Institute. Captain Sten-lund spent his first Sunday in Port Elizabeth with the Wood family at their Walmer home.

On Sunday 1 November 1942, while on an afternoon drive down to Schoenmakerskop and having just crossed the old railway line with the sea in front of them, both George Wood and Captain Stenlund gasped simultaneously as they spotted an object floating far out on the horizon It was the bows of the Anne Hutchinson passing Schoenmakerskop. The Captain commented with tears on his face, “Poor Anne Hutchison! She was burned at the stake and now she has been blown in half.” From a distance the Bows sticking up out of the ocean resembled the sail of a large sailing ship.

George Wood, realizing the danger she posed in our shipping lanes, immediately returned home and phoned the Port Captain’s office to notify them of the bows drifting the current, towards Cape St Francis. He also phoned Cape Recife lighthouse and learned that they had not seen the bows passing Cape Recife.

Once the bows were secured in the Port Elizabeth harbour, Captain Stenlund boarded his old ship to collect all of his remaining personal items, which included a set of tapestries for his dining room chairs back in the States. Tapestry work had been his hobby while on board the ship.

Captain Stenlund had left the above-mentioned canister together with the ship’s documents in my father’s office until his departure for the States. On leaving PE, the Captain removed his ship’s documents and gave the container to his friend, George Wood.

Rosemary MacGeoghegan nee Wood now still has still waterproof container from the Anne Hutchinson in her possession. Mangold Bros. salvage the valuable equipment from the wreck and shipped it all the back to the United States. The ship’s funnel was sent intact to the States, lashed to the deck of a Robin Line Ship.

The ship’s wheel was kept for many years by Rosemary MacGeoghegan’s family before passing it onto Simon Fischer, a grandson for George Wood. Simon is restoring the wheel and plans to build it into his lounge overlooking the Vaal Dam

Sources

‘https://www.wrecksite.eu/wreck.aspx?32243

‘https://uboat.net/allies/merchants/ship/2294.html

They Saw the Ship’s Better Half by Adam Brand in the E.P. Herald 1960

War in the Southern Oceans by Turner