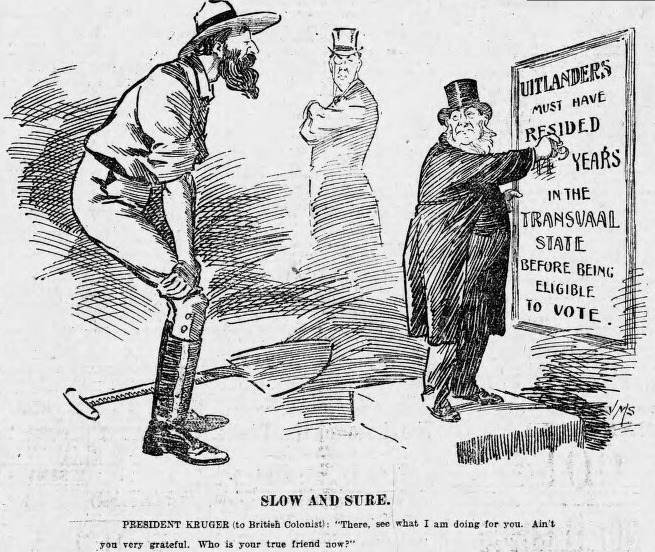

The Ango-Boer War, or as it now known, the South African War, might not have physically ravished the town, yet it did affect Port Elizabeth in manifold ways. The denial of the right to citizenship of the Uitlanders in the Transvaal Republic was the ostensible reason for the declaration of war by Paul Kruger on Britain on the 11th October 1899.

Main picture: No. 2 Remount Depot

Declaration of hostilities

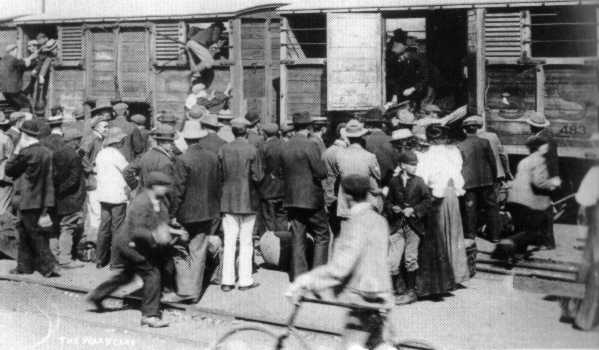

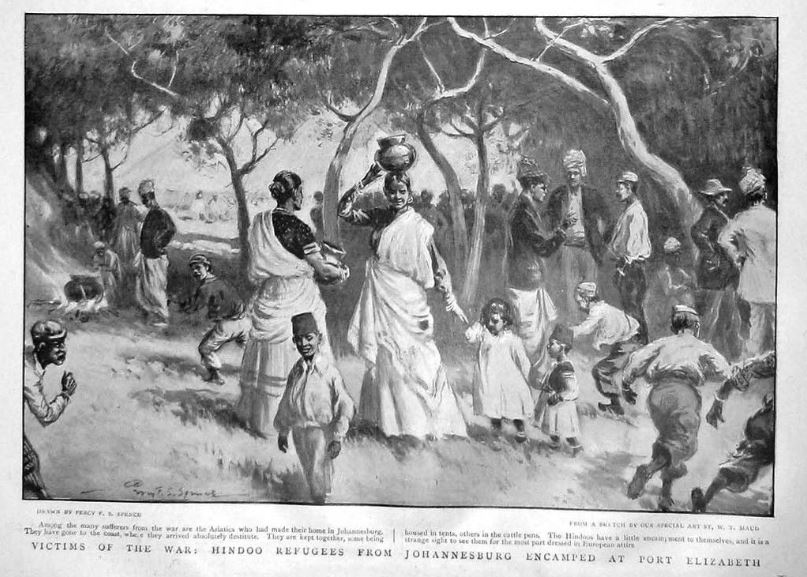

The prelude to the formal declaration of hostilities was preceded by much “war talk.” Fuelling this speculation, were the fearful Uitlanders who were streaming in overloaded open railway coaches to the Bay. Initially a refugee camp was set up at the old show ground at North End. Later on, families were relocated to the old Fairview Race Course next to Cape Road, whereas the single men and other races were moved to Prince Alfred’s Park.

Being a major port, the possibility of attack on such a strategic asset as Port Elizabeth could never be discounted. Instead, in a fit a pique, Kruger declared war without a well thought-out strategic plan in mind. The Boer advance rapidly achieved its narrow tactical objectives. Perhaps motivated by a desire not to enrage a somnambulant giant, Kruger lacked the foresight to comprehend that tormenting a vicious animal would ultimately have fateful consequences for the Boer’s sought-after independence.

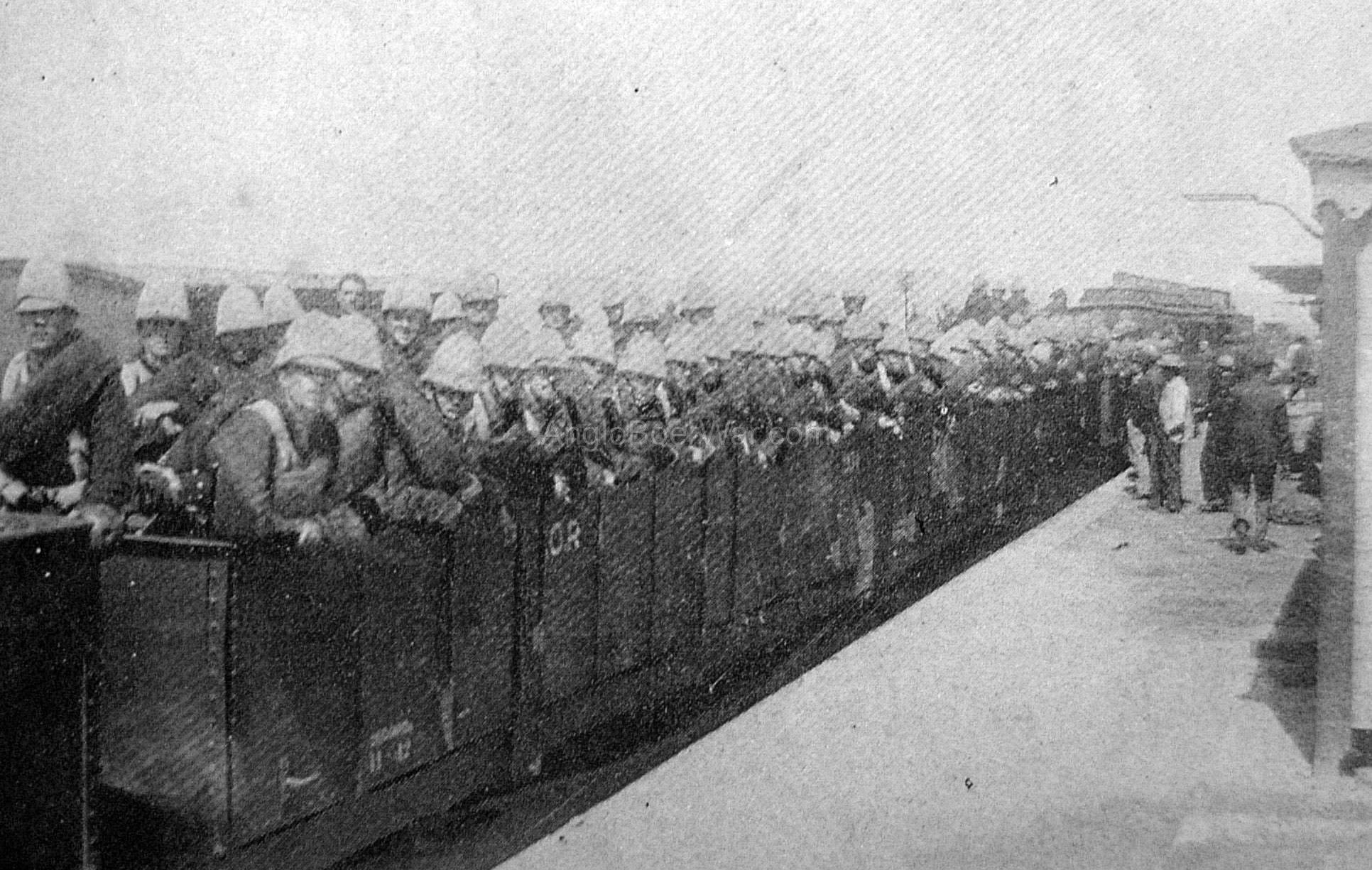

By the 31st October 1899, twenty days after the declaration of war, the first batch of British soldiers aboard the Braemar Castle would land at Port Elizabeth. This would be the vanguard of hundreds of vessels over the course of the war, lasting two and a half years. These vessels would disgorge thousands of fighting men, tons of military stores and hundreds of thousands of remounts (as horses were called) pack mules and their fodder.

Remounts

At the best of times, the unloading facilities with their archaic method of discharging their cargo onto surfboats bobbing next to the transport ship, far at sea, was inefficient. Now there was pande-monium with dozens of vessels of all shapes and sizes riding at anchor in the Bay, patiently waiting to discharge their cargoes. Priority was given as follows: troops, remounts, mules preceded by military hardware, medical equipment, mail and finally coal for the railways.

What became abundantly clear early on in the war was that the mortality rate of the horses was excessive. Instead of addressing the root cause, which was not attributable to battlefield casualties, but rather due to death at sea arising from starvation and illness and on land due to overwork or ill-treatment, the British scoured the world for horses.

Port Elizabeth was designated as the staging post for remounts. From November 1899, these remounts started arriving from as far afield as Canada, Argentina, Australia and New Zealand. This initial trickle of horses rapidly became a torrent. The rigors of the long slow sea journey claimed many horses. Then in Algoa Bay, they were hoisted from the ship into unstable buckling lighters at sea and then unloaded onto North Jetty, to be stabled at the Agricultural Show Ground at North End and at Kragga Kamma.

The scale of this remount operation can only be comprehended in terms of the number of remounts transferred from ships in the Bay to dry land at the foot of Jetty Street. According to Neil Orpen in his book on the history of the Prince Alfred’s Guard, this cumbersome laborious process was used no less than 123,000 times between November 1899 and June 1902. In addition to these remounts, the antiquated discharge method also had to cater for 46,000 troops, almost 800,000 tons of military stores as well as thousands of tons of hay. The harbour at Port Elizabeth must have been a hive of activity. One wonders whether this was a 24/7 operation as without the benefit of modern lighting, proper sources of lighting for night time work would have been problematical.

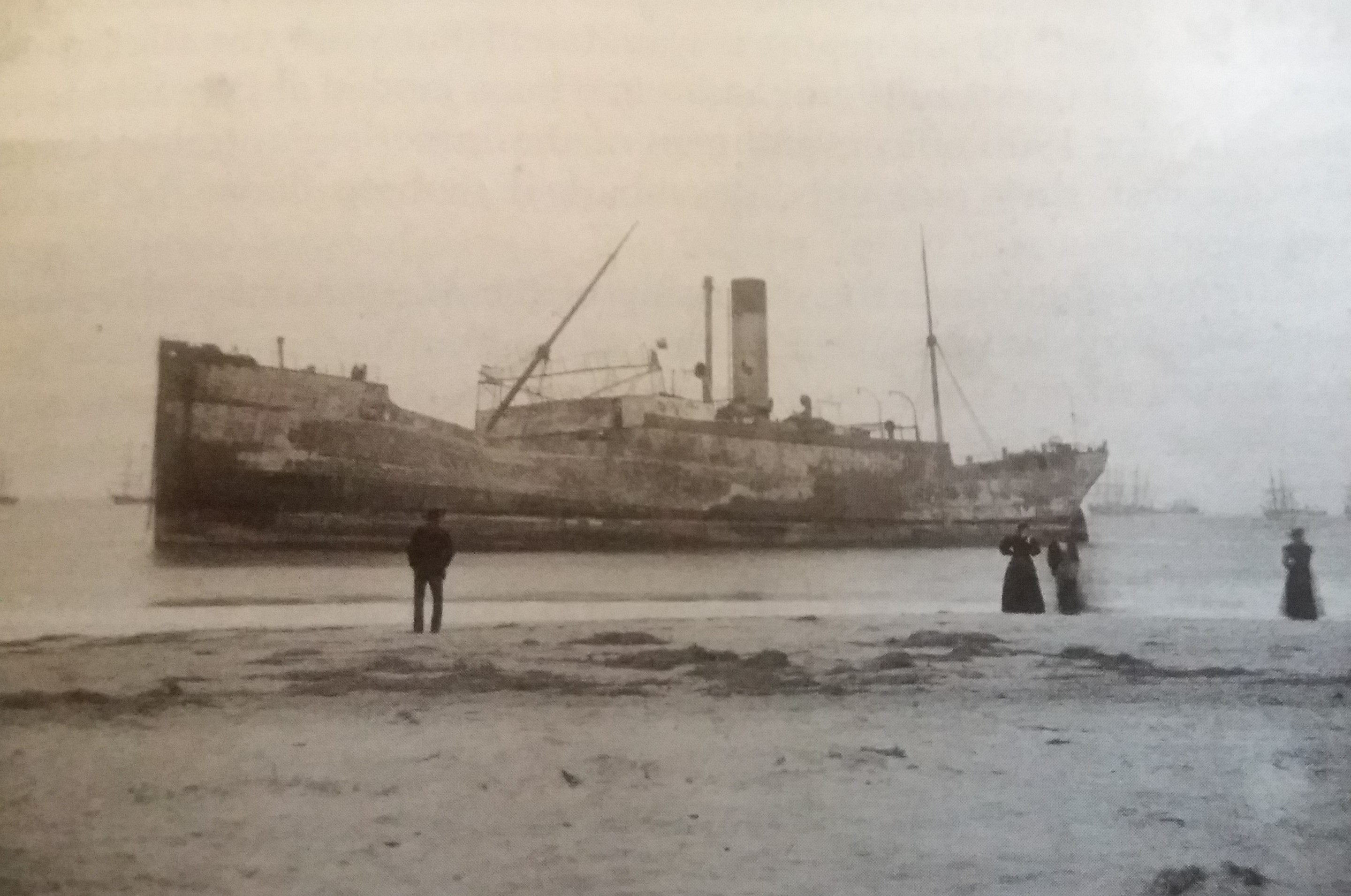

Spontaneous combustion

Not only was it the number of remounts imported but, South Africa being an arid country, unavailability of fodder was a concern. Importing hay became a priority. Notwithstanding that, another problem raised its head. Poorly cured hay can ignite spontaneously when lying compacted for a long period of time. The worst fire aboard a hay ship in the Bay occurred on the Mariposa which entered the Bay in March 1900 with 5,000 tons of hay. The ship lay at anchor in the roadstead for two months before they commenced discharging her cargo. Immediately after the labourers commenced unloading the much-required fodder, smoke began billowing from her holds. Like what would occur on many such occasions whenever ships were experiencing difficulties, onlookers and spectators would gather in their hundreds ogling the unfolding spectacle from Richmond Hill or from North End Beach. These eye witnesses watched as several tugs armed with pumps and hoses rushed to the ship’s side. Aghast, they witnessed as a pig was thrown overboard. Fortunately, it managed to survive long enough in the freezing water to be rescued.

When the fire could not be extinguished, the port authorities availed themselves of an unusual tactic. They would scuttle the Mariposa close inshore in the bight; the designated method of scuttling her was by a gunboat creating some extemporised water inlets through the simple expedient of firing shots into her hull. Thereafter once the smouldering hay had been doused, they would discharge the hay and refloat the vessel. As Robert Burns would state in his poem ‘To a Mouse’, the “best laid plans of mice and men” go awry. No-one predicted that when hay became waterlogged, it would rapidly swell and block the holes, thus preventing the ingress of water: as a consequence, the hay continued to smoulder for about a week, resulting in the loss of the cargo as well as the ship. Yet another calamity ensued when an easterly wind blew the gutted hulk further into the shallows. Ultimately, the Mariposa was refloated and towed to East London for scrapping.

As the war progressed, volumes surged. On 28th May 1900, the Herald reported that no fewer than 57 vessels lay at anchor in the Bay. Some had already been there for five months. Amongst the notable ships to arrive in June 1900 were those bearing the officers and men of the Imperial Australian Corps.

As luck and fate is fickle, how would the sister ship of the Mariposa, the Masconomo, also laden with hay, fare when discharging her cargo after arriving from Canada? As luck would have it, she too experienced spontaneous combustion in the hay. Fifty “bluejackets” from the HMS Pelorus were sent across to fight the blaze using pumps and hoses brought across by Ulundi (II). In this case, luck was on their side. After Herculean efforts, the fire was brought under control and then extinguished in toto.

Queen Victoria’s passing

As was customary throughout her widowhood, Queen Victoria spent the Christmas of 1900 at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight. By then, rheumatism in her legs had rendered her lame, and her eyesight was clouded by cataracts. Through early January, Victoria’s condition deteriorated as she felt “weak and unwell“, and by mid-January she was “drowsy … dazed, [and] confused“. She died on Tuesday 22 January 1901, at half past six in the evening, at the age of 81. Her son and successor, King Edward VII, and her eldest grandson, Emperor Wilhelm II of Germany, were at her deathbed. Her favourite pet Pomeranian, Turi, was laid upon her deathbed as a last request. The Queen of England and Empress of India was no more. She had died after 64 years on the throne and having been Britain’s longest serving monarch. With 95% of its white population of Port Elizabeth being English-speaking and mainly of British origin, her death was most keenly felt in the town. To mourn their loss, the buildings in Main Street were draped in mourning colours.

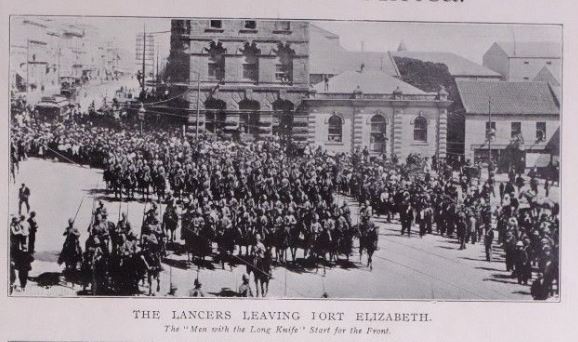

Call to arms

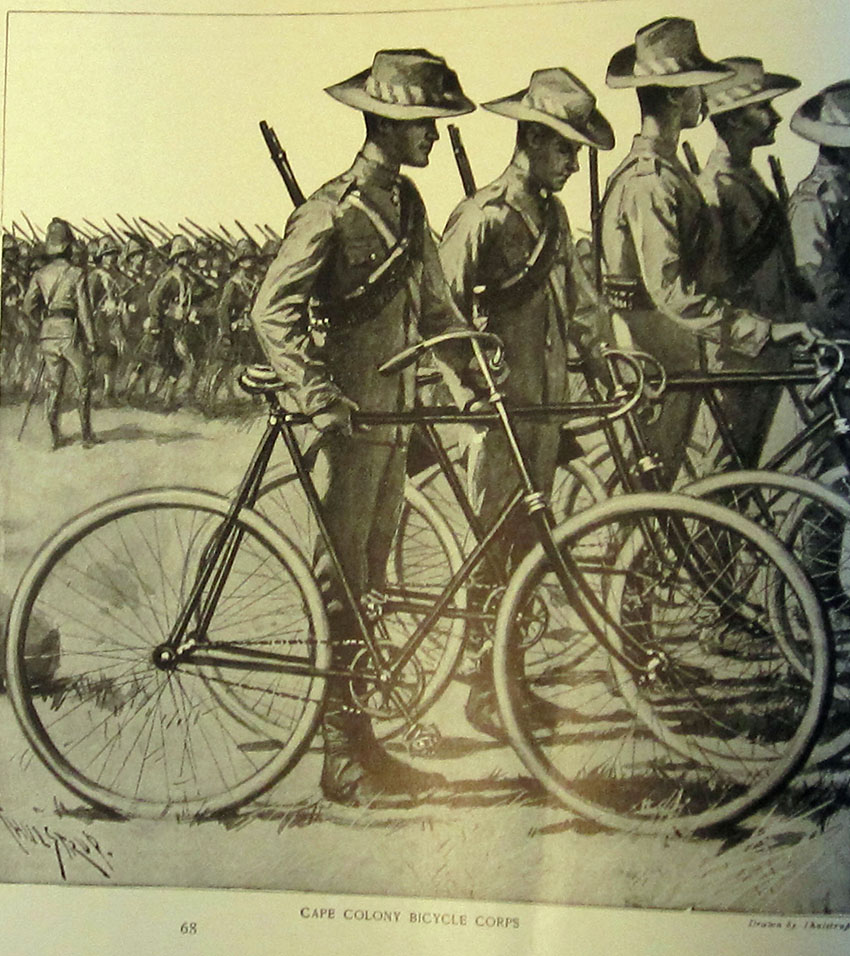

Swept up on a wave of patriotism and mourning, akin to the premature death of Diana Spencer, throughout that January month numerous advertisements appeared in newspapers calling for recruits to join the 27 or so regiments fighting against the Boer forces. Each regiment adopted a different angle to attract likely candidates. Prince Alfred’s Guards probably opted for the “local is lekker” aspect, whereas the Prince of Wales Light Horse catch phrase was “at 5s a day all found”, and the Cape Colony Cycle Corps boasted that one must “bring your own machine and get paid 2s a day extra bicycle allowance.” Naturally those opting to join a mounted regiment were expected to ride and shoot from the saddle. If an applicant was accepted into Kitchener’s Fighting Scouts, they would draw an additional 5s a day over and above the 2s, if they provided their own mount. All contracts were for six months.

Martial law

The conventional phase of the war was over. The Boers had been comprehensively beaten by the Brits albeit at huge loss to the British forces. Instead of surrendering, the Boer forces reverted to a form of warfare more suited to their skills and talents: guerrilla war. During this phase, the Boers harried the Brits mercilessly. They could rightly be called Masters of the Bush or even to turn a British phrase, Scarlet Pimpernel of the Bush. The frustrated British forces died from shots they heard, but without seeing their enemy.

As if to place an additional burden on their enemy, the Boers established a raiding party under Gen. Jan Smuts, a future Prime Minister of South Africa, who invaded the Cape. Martial law was imposed in Port Elizabeth amid fears that the Boers might raid the town. Being mounted unlike the British foot soldier, this column was highly mobile. The contingent was known to be in the Zuurberg Mountains and that some of the men had paid a visit to Bayville, just outside Kirkwood, in order to secure some desperately needed supplies. Towards the end of 1901, the Herald was once again awash with advertisements calling for recruits to join local mounted regiments, now desperate not for footsloggers, but recruits skilled in horsemanship and the use of a rifle from the saddle.

In Port Elizabeth, there were advertisements for at least 20 mounted regiments, including the Port Elizabeth Mounted Corps, Robert’s Horse, Kitchener’s Fighting Scouts, the Imperial Light Horse, Prince Alfred’s Guards Mounted Infantry and the 1st Brabant’s Horse. For recruits to the Cape Colony Cycling Corps, duties would include guarding communication lines and / or delivering despatches. “Applications were to be received by Lt. J.C. Williams at the Port Elizabeth Town Hall” or by the “Recruiting Officer at the Feather Market.”

Beginning of the End

Much like a symphony, the war was reaching a crescendo. The end was nigh, but the date was uncertain. From early January 1902 the crescendo arose with the number of ships in the Bay reaching an all-time record of 75 with 43 being steamers and 32 sailing ships, taxing the facilities to the utmost.

On the 9th June 1902, the final note was played as the official declaration of the cessation of hostilities came into effect. Boer hardliners known as the bittereinders continued to fight, vowing never to surrender. In spite of the cease fire, martial law in Port Elizabeth was only repealed in September 1902. Notwithstanding the war’s end, the harbour would be taxed for many years to come as the constant inbound flow reversed direction as men and materiale returned to their homelands.

Refugees during the Boer War

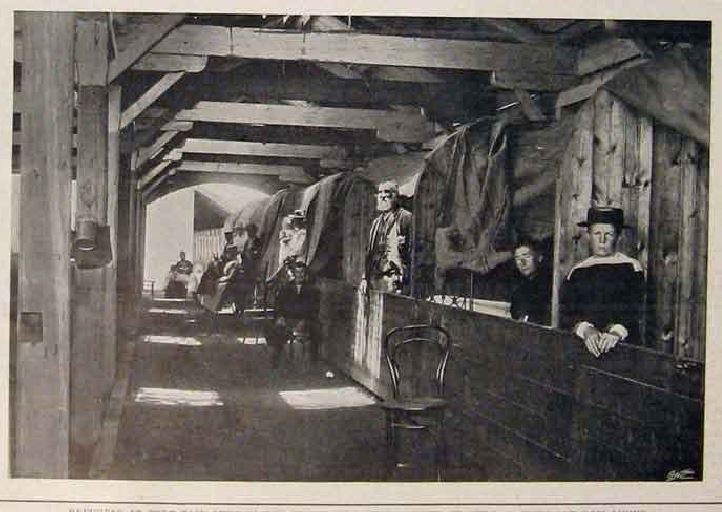

Port Elizabeth was also another sort of harbour of refuge. On the outbreak of the Anglo-Boer War, hundreds of “Uitlanders” fled from the Transvaal and many of them arrived in Port Elizabeth. The citizens of Port Elizabeth were quick off the mark and immediately set up a Refugee Relief Committee under the chairmanship of the Mayor, Councillor M. Gumpert. Many well-known local names featured in the list of committee members – Pyott, Geard, Mosenthal and others. The Show Ground was commandeered, and the produce sheds turned into dormitories. A newspaper report said that 568 Europeans, 106 Indians and 61 “unclassified denizens” were living amicably side by side.

However, the camp had hardly been established when the military wanted the showground as a remount centre, and new plans had to be made. A new “township” was started at the racecourse for the Europeans, with wood and iron dwelling-blocks being erected. In addition, three separate camps were established in Prince Alfred’s Park, one for Jews, one for Indians and one for Coloureds and natives. Here the buildings were less substantial, being tents and structures with sacking walls.

For hygienic reasons, rigid rules were drawn up, medical staff appointed, and there was even a librarian. The pamphlet which contains an account of the camps has an amusing sketch of one day’s routine in the camp written by one of its inmates. Statistics show that the cost of the camps was only 10 7/8d. per head!

And yet according to the account, the food was adequate and palatable.

Sources

Algoa Bay in the Age of Sail 1488-1917 – A Maritime History by Colin Urquhart (2007, Bluecliff Publishing, Port Elizabeth).

Wikipedia