Just like the fact that the destruction of South End is an integral part of Port Elizabeth’s history, so is the paint theft which culminated in the Defiance Campaign. How did such a minor issue transmogrify into a riot? It was the sense of displacement and discrimination that the Black population had endured from the time of their relocation from the inner-city locations such as Strangers’ Location in Russell Road and Gubb’s Location in Mill Park. Perhaps this was the defining moment when forever White domination in South Africa would be under siege.

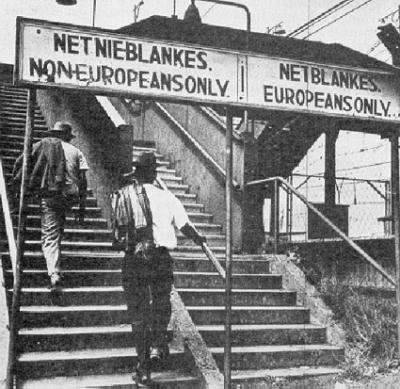

Main picture: New Brighton Railway Station

Jimmy’s story

The riots in Port Elizabeth were sparked by a charge of theft which ultimately left 11 dead in its wake. The other day I had a conversation about the history of New Brighton when it was still regarded as a model township. But the conversation really centred on the October 18, 1952, “paint riots” which left 11 dead, seven of them blacks, 27 injured and eight buildings, including the plush Rio Cinema, wrecked in what was regarded by the media as a night of murder, arson and mob violence. I still remember this newspaper with a front-page headline on Monday, October 20, screaming: “Armed police quell bloody riot at New Brighton townships”. The opening of the Rio bioscope in 1950 was an important milestone in the cultural life of the residents. For too long residents had to travel distances to go to bioscopes outside the townships such as the Palace in South End, the Avalon in North End or the Alpha and the Star in Korsten, having to brave racial attacks by the coloured community.

For the sake of space, I will try to reconstruct briefly what I witnessed on that fateful day. It was on the afternoon of Saturday, October 18, 1952, when New Brighton exploded in flames. It all started at the New Brighton railway station when a railway policeman tried to arrest two men who were alleged to have stolen a gallon of paint at North End station and boarded a train to New Brighton. The two men resisted and a scuffle ensued. Other passengers, joined by people from the Red Location, came to the assistance of the men. They threw missiles and the constable, perched on the whites-only side of the railway bridge, opened fire.

In flight from police shootings, the enraged mob made its way deeper into the location and the first victim to die was a W M Laas, a white man, who had given black fellow workers a lift home. Shops managed by whites were attacked. On that Saturday, Rio bioscope was showing a western movie, The Gunfighter, starring Gregory Peck. It had packed the house for a week. Just before the mob, armed with a variety of missiles, arrived at the Rio, some sympathetic people warned bioscope manager Rudolph Brandt, his wife, Edith, and their assistants to leave, but Brandt refused, saying the Africans were his people and would not harm him. Only his assistant manager, George Thomas, successfully fled in his car which came under a rain of stones. The cafe in the foyer was looted and Brandt’s car was torched. He, his wife, a technician, Gerald Leppan, his assistant, Karl Bernhardt, and Leppan’s 15-year-old son, Brian, found themselves trapped in the projection room when the building was set on fire. Later the five appeared with Brandt giving the ANC’s “Mayibuye Africa” salute – right hand with a clenched fist and the thumb pointing backwards – emerged in an attempt to exit via the fire escape. But even that demonstration of allegiance to the ANC did not deter the mob from immediately dragging, attacking and callously stabbing them.

Brian managed to escape with minor injuries and sought refuge under a bed in the Grattan Street home of a headman. From there he was whisked out of the township by the late Rev Douglas Mbopa to safety. While Brandt lay on the ground and still shouting “Mayibuye Afrika”, he was murdered, his wife was dragged across the concrete road, brutally gang-raped and assaulted. She was saved from death by the arrival of a police kwela truck, which was greeted with a hail of stones, and the police retaliated by opening fire on the crowd, which fled. The next morning an eerie calm prevailed, with some people returning to the wrecked bioscope in search of what they could salvage, possibly money. Today, the rebuilt cinema, which resumed its activities under black ownership, has been converted into a R300 000 Pro-Cathedral Kaizer Ngxwana of the Church of Umzi waseTopiya (Traditional Rite), under Bishop Michael Mjekula. The spirit of resistance and opposition to white rule and police brutality was ignited by the Defiance Campaign against unjust laws, which was nationally launched on the morning of June 26, 1952, when Raymond Mhlaba led the first group of 30 volunteers through the “Europeans Only” entrance at the station.

A personal note

As my mother was three months pregnant with me, her first child, when this riot erupted, I was not aware of this event until some ten years later when my mother discussed the events of that fateful day with me. The lessons learnt by the whites were not as clear-cut. Cast in stark relief was the fate of bioscope manager, Rudolph Brandt, who had rightly regarded the black people of the townships as his friends and hence not to be feared. In the white community, it lamented the blacks actions for their duplicity and untrustworthiness due to his violent death.

Muddying this facile narrative was the fact that Brian Leppan managed to escape with minor injuries with the aid of various black members of the community. Firstly, Brian sought refuge under a bed in the Grattan Street home of a headman. From there he was whisked out of the township by the Rev Douglas Mbopa to safety.

By placing the white community on notice in such a barbarous manner, they did not endear themselves to their white compatriots but by the 1960s such foreboding had largely dissipated.

List of Apartheid Legislation:

Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act, Act No 55 of 1949

Immorality Amendment Act, Act No 21 of 1950; amended in 1957 (Act 23)

Population Registration Act, Act No 30 of 1950

Group Areas Act, Act No 41 of 1950

Suppression of Communism Act, Act No 44 of 1950

Bantu Building Workers Act, Act No 27 of 1951

Separate Representation of Voters Act, Act No 46 of 1951

Prevention of Illegal Squatting Act, Act No 52 of 1951

Bantu Authorities Act, Act No 68 of 1951

Natives Laws Amendment Act of 1952

Natives (Abolition of Passes and Co-ordination of Documents) Act, Act No 67

Native Labour (Settlement of Disputes) Act of 1953

Bantu Education Act, Act No 47 of 1953

Reservation of Separate Amenities Act, Act No 49 of 1953

Natives Resettlement Act, Act No 19 of 1954

Group Areas Development Act, Act No 69 of 1955

Natives (Prohibition of Interdicts) Act, Act No 64 of 1956

Late 1950s

Bantu Investment Corporation Act, Act No 34 of 1959

Extension of University Education Act, Act 45 of 1959

Promotion of Bantu Self-Government Act, Act No 46 of 1959

Coloured Persons Communal Reserves Act, Act No 3 of 1961

Preservation of Coloured Areas Act, Act No 31 of 1961

Urban Bantu Councils Act, Act No 79 of 1961

Terrorism Act, Act No 83 of 1967

1970s

Bantu Homelands Citizens Act of 1970