One misconception about the Malays in South Africa concerns the nomenclature “Malay.” In fact they originate from Indonesia. However, for simplicity’s sake, we will continue to use the word Malay for the purposes of this chapter. Another erroneous notion is that Malay population only arrived after the British settlers.

This chapter rebuts these fallacies. It also reveals the important role the Malays played in the development of Port Elizabeth.

Main picture: The Green or Pier Street Mosque

Origin of the Malays in South Africa

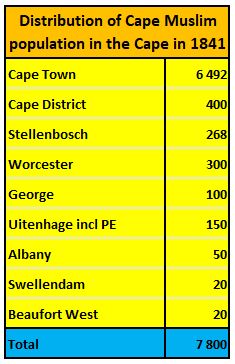

The history of the Malays in Port Elizabeth is inextricable linked to that of the Malays of Cape Town. In fact the story of the Malay population in the Cape goes back at least seven generations and more than 350 years. In 1652, Jan van Riebeeck arrived in South Africa and the Dutch East India Company brought with them slaves, political exiles and members of the royal family from Malaysia, Indonesia (formerly Java) and other countries. Although the date of his arrival is not known, the Sultan was among them.

Their descendants can still recount how, when the king and his entourage boarded ships to bring them to South Africa, they were forced to leave any personal documentation, religious literature and identification in drums next to the gangplanks.

Initially the Malays settled in Cape Town, which became home to the majority of Malays in South Africa. It is apparently the biggest Malay community outside Indonesia. In 1806, part of this community numbering 89 according to Margaret Harradine, left Cape Town to settle in Uitenhage. The pioneer of the Malay community was Imam Jabaarudien, also known as Abdul Maalick or Jan Bardien. Born in 1784, Bardien was the grandson of Sultan Nabier, and he arrived in Uitenhage in 1815 and built the first mosque there, Masjid-Al-Qudama, in the 1840s.

First Malays in Port Elizabeth

From there certain members must have sought better opportunities in Port Elizabeth. Their reasons ranged from the avoidance of military service against the British to travellers with the Trekboere of late 1700s. Amongst the Malay people living in Port Elizabeth in 1819 was a certain Fortuin, listed as being a blacksmith. Even though he probably was only listed due to his prominent status as an energetic and successful entrepreneur, it is possible that other itinerant Malay fishermen were already located in Port Elizabeth.

Fortuin Weys was so successful that he acquired various properties in the newly established town. This is what is known about this enterprising person.

On page 98 of his thesis on the development of the harbour in Port Elizabeth, Jon Inggs includes this comment regarding Fortuin:

“The only other improvement to port facilities during this period [1820s] was the provision of water to ships by a Malay, Fortuin Weys. He erected a pump and laid pipes from it to the landing beach. Weys by 1834 was described by Thomas Pringle as ‘one of the wealthiest and most respectable inhabitants of the place’. He had originally been granted land at Algoa Bay in March 1820. By the time the settlers landed, his house, still under construction, was the second substantial one to be built at what was soon to become Port Elizabeth. He was listed as a blacksmith by Griffin Hawkins in 1822. In time he acquired a number of properties in the town and further afield”.

“In January 1839 the executors of the Weys’ estate put up for sale: 29 building lots, 3 other properties, a 6,5 hectare smallholding on the Baakens and a 1013 hectare farm, Doorn Nek, near the Zuurberg – GTJ 3/1/1839 p 1. The Baakens property was known as Fortuins Valley – GTJ 26/3/1840 p 1. As late as 1890 his executors became involved in a legal wrangle over land reclaimed along the Victoria Quay, adjacent to Weys’ land – PEPL Weys’ file.

In his article entitled, “The economic history of the Port Elizabeth-Uitenhage region“, André Müller confirms Jon Inggs’s assessment of Fortuin as follows:

“But the most famous entrepreneur was a Malay, Fortuin Weys, whose house was among the first to be built in Port Elizabeth, and who became one of the wealthiest residents of the town”.

Pringle recalled in 1834: “On the 6th of June [1820], we assisted at laying the foundation of the first house of a new town at Algoa Bay, designated by Sir Rufane [Donkin] Port Elizabeth, after the name of his deceased lady. In the course of fourteen years this place has grown up to be the second town in the colony, both for population and for commerce; and it is still increasing. Captain Moresby, of the Navy, was the proprietor of the house then founded with much ceremony, and of which our party assisted to dig the foundation. The only other house then commenced, excepting the temporary offices and cabins already mentioned, was one erected by a Malay named Fortuin, now, I understand, one of the wealthiest and most respectable inhabitants of the place. As a blacksmith, Fortuin was one of the earliest industrialists in Port Elizabeth. In the 1820s he also improved the provision of water to ships by installing a pump and pipeline which carried water to the beach”.

What is certain is that the main body of Malays arrived in Port Elizabeth in 1846 when a number of those who had fought for the Colonial Army against the Xhosas, decided to establish themselves in Port Elizabeth and Uitenhage. In the 1849 Directory of Port Elizabeth, seventeen Malays and their families are mentioned of which 11 lived in the so-called Malay quarter.The presence of Malays between Main and Strand Street was established when a mosque was built in Grace Street with assistance from the Turkish Sultan, Abdul Majid. On 7 December 1855, land was granted to the Malay community south of the Baakens River. A portion of this land was to be used as a cemetery. The Malay community had grown so prolifically that a second Mosque was built in 1866 in Strand Street.

Early Port Elizabeth was characterised by the settlement of immigrant communities which included European and Cape Malay communities. The diverse community lived together according to economic and social status, rather than on an ethnic basis. However, when the Group Areas Act was legislated in 1950, this resulted in forced relocation under the apartheid law of the non-white population and the townships came into being.

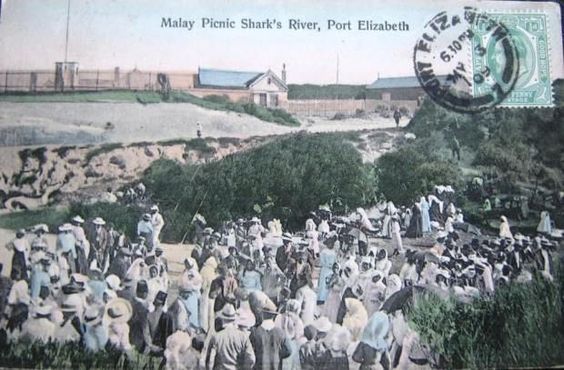

In the area now called South End, Malay fishermen had already lived along the coast south of the Baakens River for a long time. The Malays also bought some of the first plots that were offered for sale south of the Baakens River in 1859. According to Nel, “Maleiers het ook aanvanklik erwe in die nuwe woonbuurt gekoop wat toe ‘n permanente Maleierteenwoordigheid van die staanspoer af in Suideinde verteenwoordig het”. The Malay quarter consisted of the area between the Main and Strand Street. All of the Malay families except three, would have been unaffected by the expansion program of the Railways at the time. Even though a record cannot be traced of the forced relocation of the Malays from the quarter to South End, one can surmise that it was indeed forced. The central area of the town was being developed and Malays, regarded as non-white, had to move. “Met die gedeeltelike sloing [demolition] van die Maleier buurt wat as a kernwoongebied gedien het, is die groep se teenwoordigheid suid van die Baakensrivier numeries verstrek”.

Source: G.J. Nel, M.A. Dissertation, UPE, 1987

Catering for the Muslim’s spiritual needs

By 1804, the number of the Vryezwarten or Free Blacks, the majority of whom were Muslims, had reached such a significant proportion that the Dutch rulers changed their policies in order to enlist their support to face the impending British invasion of the Cape. They granted religious freedom to the Vryezwarten. Thus on 25th July 1804 the patience and perseverance of the Cape Muslims was rewarded when religious freedom was permitted for the first time at the Cape of Good Hope.

Prior to this, the Cape Muslims, in practising their religion, were severely restricted by the Statutes of India, a set of laws particularly aimed at restricting the religious practices of the Muslims of the Batavian Empire of which the Cape formed a part.

On 4th May 04 1846 the “Malay Corps” of 250 Cape Muslim volunteers left Cape Town in two boats for the Eastern Frontier because of unrest in that part of the Colony. They remained there until 16th September 1846 when the “Malay Corps” was demobilised after the Battle of the Axe in the same year. Those who did not return to Cape Town settled in the Eastern Cape. They were in all probability responsible for the construction of the Uitenhage Masjid together with the initial batch of 89. This was the fourth masjid to be built in the country.

Being highly religious, and Muslim to boot, the nearest mosque and imam for the Muslims residing in Port Elizabeth was in Uitenhage. In accordance with their devout religious beliefs, all the Malays residing in Port Elizabeth were compelled to travel to Uitenhage every Thursday in order to attend Friday prayers at the mosque. This act illustrated their devotion to their faith which is still prevalent today.

After nearly a decade of trudging from Port Elizabeth to Uitenhage every week, in 1855 the Malay community in Port Elizabeth was eventually able to commence construction of the Grace Street Mosque, the Masijied-ul-Akbar. Furthermore a Malay burial ground was granted adjacent to the St. Mary’s cemetery in the lower Baakens Valley. Illiquidity brought the mosque construction to a halt. The building work was rescued when the Sultan of Turkey donated the money required to complete its erection.

As the majority of the Malay community, mainly fishermen, lived in the Strand Street area, yet another mosque was built a short distance of the Grace Street Mosque. In those days, prior to the construction of the Victoria Quay, Strand Street abutted the sea shore.

The first imam of this mosque was Aboo Rafie and the architect was F.M. Pheil. Again the Sultan of Turkey contributed to the construction of a mosque in the amount of £500. The Strand Street Mosque was officially opened on the 1st June 1866. Thirty four years later in 1900, this narrow site was sold on behalf of the Muslim community and the mosque was demolished the following year.

South End

Originally the entire area that is now known as South End was part of a farm called Papenbietjiesfontein. In time it was given to the municipality and, shortly thereafter, the bulk of it was divided into plots and sold to the Malays. Before long, the flourishing community of South End started to develop. The earliest Cape Malays who had helped to establish the community here were not noteworthy in themselves. However, as a people, their role as pioneers and their devotion to the Islamic faith were of the utmost importance. These early pioneers maintained the religious practices of the Cape and these have passed down over the generations regardless of where their descendants chose to settle.

Again travelling distances to pray at the mosque were problematic. To overcome this hindrance, on the 4th September 1893 plans were put forward to construct a mosque in South End itself. After agreement was reached, a mosque called Masjied-ul-Abraar was built in Rudolph Street. It now faces Walmer Boulevard as all the old South End Streets were obliterated.

This mosque was in turn unable to handle the number of worshipers so plans were made to construct yet another mosque in South End. On the 27th July 1901 the Pier Street Mosque, Masjied-ul-Aziz, was opened.

On the 10th November 1915, the Humphries Street Mosque, the Masjiedun Nabawi, was opened.

Biography of Soudien Bardien

Soudien Bardien or Jabaar-u-Dien, a local Malay boatman was one of the most well-known local coxswains, “who dressed appropriately”. A former tailor, Soudien was listed in the Cape of Good Hope Almanac of 1849 as the port coxswain at an annual salary of £52. His six crewmen received £40 per annum each. According to reports, Soudien was considered “the most skillful of boat handlers under any conditions, never having capsized or lost the port boat during his time at the helm. He and his men are credited with saving an uncounted number of shipwrecked sailors over the years. During the gale of October 1859, Soudien was praised for his skill not only in the numerous trips made to sea under very bad conditions, but also in saving an unnamed Mfengu who got in beyond his depth. On one occasion when Murdock Mackenzie was struck on the head by an oar and drowned as the surfboat broached the waves, it was noted that Bardien had not been aboard. The townsfolk generously donated £120 to Mackenzie’s widow and two children”.

“Soudien once more received praise in the Herald when he and his crew went out to those in need during a gale in 1869. He retired soon after, living on a ‘liberal’ pension granted to him by the Harbour Board in recognition of his faithful service and in acknowledgement of his ability and worth to the maritime community. He died on 23rd July 1873, aged 64, at his house in Britannia Street, just behind the Grace Street mosque that he had so faithfully attended. A public subscription was opened to assist his widow and family”.

Biography of David Doit

Better known around town as “Darby the Whaler”, he appeared on the local scene in the latter half of the nineteenth century, after having spent time in Grahamstown. He went to work first for the Port Elizabeth Boating Co. as an oarsman and then as a coxswain, a job that he held for close to twenty years. In their spare time, he and his crew would go whale hunting. As time passed, the skills of this two-metre tall Malay became legendary. The “gentle giant with a reputation for being fearless, was said to be capable of firing a 40 lb brass gun from his shoulder while standing firmly in the bow of the whaleboat”. More often than not, the result would be a whale landed on North End Beach, where it would be cut up and the oils extracted. For this, Doit and his men would earn as much as £300 with an extra £50 going to the coxswain in recognition of his skill. Doit’s exploits sometimes filled a column in the local newspapers. In August 1891, it was reported that “with a lucky throw”, he harpooned his eighth whale that year, the five skilled oarsmen making up his crew, taking him in very close for the kill. Three years later in May, he was again reported to have harpooned a whale, and the fact that it sank suggests that this was not the usual Southern Right. It was practice during this period for as signalman to be left on St. Croix Island to alert whalers to sightings by lighting a fire. In August 1896, after receiving the signal, Doit and his men set out in one of Searle’s boats and harpooned a whale off the island. He was forced to let it go as dusk fell. Undaunted, they went after a female the next day and succeeded in bringing it back to North End. Doit’s skills as a coxswain were frequently tested under extreme conditions when ships came ashore, as in 1897 when the Cambusnethan grounded along the Alexandria coast. The tug, Sir Frederick, was despatched to the scene with Doit and his whalers in tow to assist in the rescue attempt. In June of the following year, they again set out after a whale war sighted in the Bay. When the harpoon sank into its body, it turned and attacked the boat, causing severe damage. Doit received £10 from the Emperor and the King of Germany Award for his part in the rescue of the crew of the German barquentine Ludwig wrecked in the Bay in November 1899. During the South African War, he was selected by the British to lead and supervise a hand-picked crew to land military stores along the Zululand coast. Doit died, aged 65, at his home in South Union Street on the 4th October 1903, surrounded by family and the steersman – Abdul Salem Madat – and crew of his boat Weltevrede. His descendants, some of whom live in the City to this day, are believed to have taken the surname Davids or Dawood. It is said that the Southern Right skeleton hanging in the Bayworld museum was another victim of Doit’s accurately thrown harpoon.

Email from Roekeya Bardien:

“The mosque built in Uitenhage was the first mosque to be built in SA as all the other mosques were homes of families which had been converted into mosques but the one built by Jan Bardien was the first one to be built out of the ground as a mosque. Jan Bardien received the land where the mosque stands as part of a settlement for his service in the war and he decided to settle in Uitenhage. He left the mosque and the ground that it stands on, to the Muslim Community of Uitenhage in his will. I have a copy of this will. He had a sister, Sina, who he bought out of slavery. Her real name was Gasina. Gasina Bardien married Badrudien Abader. They had a son Shuhood. Gasina passed away young. Jan Bardien must have loved his sister very much, because he transferred his affections to her family”.

“Shuhood inherited a small amount from the old man as well and Badrudien later married Jan’s adopted daughter. Shuhood had a son Ayoub. Ayoub had a son, Armien (my father). Also, our surname is supposed to be Abader. The registration of the children with Bardien & Badrudien led to confusion and we ended up having Bardien as surname. They were all in Uitenhage. My grandfather, Ayoub, later moved to PE. Such a small town with such rich history, Uitenhage, especially for Malays in EC”.

Sources

Port Elizabeth: A Social Chronicle to the end of 1945 by Margaret Harradine (1996, E H Walton Packaging Pty Ltd, Port Elizabeth)

Port Elizabeth in Bygone Days by J.J. Redgrave (1947, Rustica Press)

Early Port Elizabeth harbour development schemes, 1820-1855 by Jon Inggs, South African Journal of Economic History, 6(2), 1991, p 41

Narrative of a residence in South Africa by Thomas Pringle, , London, 1824, p 21

Liverpool of the Cape E.J. Inggs, unpublished MA thesis, Rhodes University, 1986, p 98

Algoa Bay in the Age of Sail 1488-1917 – A Maritime History by Colin Urquhart (2007, Bluecliff Publishing, Port Elizabeth)

The Malays of P.E.by Gillimaufry [Looking Back, Volume 20, Number 2, June 1979, Page 57]

Once again, most interesting.

From: Roekeya Bardien [mailto:roekeya@damonabadia.co.za]

Sent: Sunday, 19 March, 2017 3:20 PM

Yes, very interesting. Just a correction…the mosque built in uitenhage was the 1st mosque to be built in SA…..all the other mosques were homes of families which were converted into mosques…but the one built by Jan Bardien was the 1st one to be built out of the ground as a mosque. Jan Bardien received the land where the mosque stands as part of settlement for his service in the war….and he decided to settle in uitenhage. He left the mosque and the ground it stands on to the Muslim Community of Uitenhage in his will….I have a copy of this will. He had a sister, Sina, who he bought out of slavery. Her real name was Gasina. Gasina Bardien married Badrudien Abader. They had a son Shuhood. Gasina passed away young. Jan Bardien must have loved his sister very much, because he transferred his affections to her family.

Shuhood inherited a small amount from the old man as well. And Badrudien later married Jan’s adopted daughter). Shuhood had a son Ayoub. Ayoub had a son, Armien (my father).(Also, our surname is supposed to be Abader….registration of the children with Bardien & Badrudien led to confusion and we ended up having Bardien as surname. They were all in Uitenhage….My grandfather, Ayoub, later moved to PE. Such a small town with such rich history….Uitenhage….especially for Malays in EC.

Roekeya Bardien

Damon Abadia Projects (Pty) Ltd

BSc.Quantity Surveying (UPE)

083 475 8978

Thanks for that information, Roekeya. I have added your comments almost verbatim into my blog. As one of my plans is to write a blog on the Mosque in Uitenhage, is it possible to scan some pages of those original title deeds to me. Secondly when I wrote the blog, I battled to find any photographs of Malays staying in South End. Do you perhaps have some as it would make the blog more authentic. Lastly my intention is still to write a blog on the forced removals from South End. Do you perhaps have any poignant photographs of that despicable episode? My email address is deanm@orangedotdesigns.co.za

Hi have u been to the south end museum- rich history of the malays

The word Malay can only mention if you put Cape Malay (sic) choirs in it incidentally consists mostly of Christian Gospel choirs members and sing sexist and racists innuendo songs caleed “moppies” This choirs was an creation of an Racists Afrikaner Prof ID Du Plessis which was an demigod of the Cape Muslims or Slamse or Mohammedans as they were reverts and not have Malay DNA but have either Dutch British or Khoisan in the social makeup .That why you do not find these

“Choirs” sic in PE,Kimberely or Johannesburg where Malay camps was established . Before the 1900’s there were no Indonesia,Malaysia Singapore and Brunei as this part was called the Nusantra and was inhabited by Malays and they spoke Melayu.