Having obtained a commission from the Royal Geographical Society to explore and investigate Africa west of Delagoa Bay, James Edward Alexander was thrust into the Kafkaesque world of the 1835 Frontier War for which he might not have purchased front row seats, but they were not the cheap seats from which the action is barely visible. Port Elizabeth itself might not have been engulfed in the war but the hordes of African warriors knocked on its front door, the Sundays River.

This blog details the defensive lines constructed, military plans drawn up and other martial actions undertaken

Main picture: Port Elizabeth’s Defence Lines during the 1835 Frontier War

Prologue

Upon arrival at the Cape of Good Hope, Alexander found the whole of South Africa to be in uproar. The Zulu impis had invaded Portuguese East Africa and seized the Portuguese fort at Delagoa, the ultimate destination of James Alexander. In the process, they had slain the Governor and some of the people. Almost simultaneously, the amaXhosa had irrupted into the eastern Cape, looting homesteads, igniting barns and slaughtering cattle. Faced with the prospect of anarchy and mayhem on the eastern border, the Governor, Sir Benjamin D’Urban, set off without hesitation for Port Elizabeth. On hearing of this, Alexander resolved to proceed after him to offer his services to him.

Alexander goes on to say that he “tarried but a few days in Cape Town, and then sailed for Algoa Bay in H.M. ship Wolf. After being under close-reefed topsails for two or three days, they took advantage of a westerly wind. As they rounded Cape Recife, the white houses of Port Elizabeth came into view.” Alexander observed that “the shores were generally low and sandy with scattered bush. In the interior are ranges of primitive mountains. H.M.S. Trinculo and eight merchantmen, lay at anchor off the town which had risen from three huts in 1819 to one hundred houses in 1835 and is distinguished by a fort on an elevated site, a church, and a pyramid erected to the memory of Lady Elizabeth Donkin after whom the town is named.”

“It blew a furious north-wester as we approached the anchorage. Sand and locusts covered our decks. The sea was alive with struggling plagues and the captain’s monkey chattered with delight and ran up the rigging ‘crunching’ them [by the] dozen. The signal was displayed from the Trinculo ‘to land stores immediately’. The Wolf was ‘working up like a duck’. We saw long trains of wagons approaching the beach and surfboats put off for us the moment that the anchor was let go. The blue-jackets were in high spirits, anticipating a fight, and worked ‘double tides’. I landed in a surf-boat piled high with camp kettles and entrenching tools.”

On landing, Alexander enquired whether Graham’s Town had been abandoned yet. Apparently, Colonel Smith had arrived in the nick of time as its saviour. In panic, some people had already fled both from Graham’s Town and from Uitenhage in order to embark for the Cape. Colonel Thomson of the Royal Engineers had confirmed to him that they were preparing to defend Port Elizabeth. Thereafter he proceeded to join Colonel Thomson’s mess at Scorey’s Hotel which he personally rated as excellent.

The following morning, Alexander set off on foot to reconnoitre the town, “wading through the sand of the long street” which was probably Main Street. Here he met a patrol, comprising of a dozen English and Dutch – as the English referred to the Dutch-speaking colonists – who had just arrived from the country. Alexander describes their bizarre, unconventional attire as “party-coloured jackets and trousers, with broad-brimmed beavers on their heads, thickly shaded with black and white ostrich feathers”. Alexander also reflected on their weapons: “Each man grasped a carbine or had a double-barrelled fowling-piece set on his thigh. Powder-horns and hairy ball-pouches hung from their shoulders and encircled their waists, and they rode active long-tailed horses.” It must have been Alexander’s previous experience as a Captain in the 42nd Highlanders which enabled him to comment that “one essential was wanting in their equipment. They had neither long knife nor sword for close combat. I don’t admire always ‘firing at a foolish distance’”.

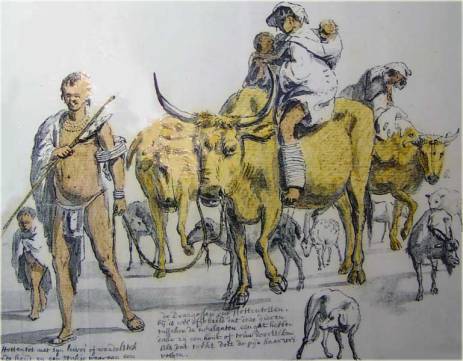

Martial preparations were evident everywhere. On the table-land above the town – presumably he was referring to the Donkin Reserve – he espied a squad of merchants and tradesmen of the town, drilling under Lieutenant Brabazon of the 75th Regiment. Below were “Hottentots” in moleskin jackets and leathers, marching and wheeling. According to Alexander, even the little black urchins usually begging in the streets were swept up by the martial sights and sounds. Instead of their usual doleful refrain, even they adapted to the occasion by calling out to each other, “Daar loop de Kaffir. Skeet hem dood!”, probably oblivious to the incongruity of the situation.

The day after his arrival at Port Elizabeth, Alexander was to meet a valued friend, Major Michell, Surveyor-General and Civil Engineer of the Cape of Good Hope and an officer in the Royal Artillery.

Alexander was requested to consult Major Michell regarding his movements and to follow any advice or instructions issued. Major Michell had been surveying the primaeval forests of the Tsitsikamma when the Xhosa invasion commenced. He immediately left for Port Elizabeth to assist the elderly Commandant Francis Evatt and a competent Mr J.O. Smith in making arrangements for the defence of Port Elizabeth. Already the Xhosas had penetrated as far as Bushman’s River and were daily expected to make an attempt to seize Port Elizabeth. In light of the deteriorating military situation, some defensive measures had to be arranged to prevent a surprise attack. To this end, the male inhabitants, black and white, numbering about three hundred, were posted to one corps, divided into eight sections, each of which was commanded by a Captain and each possessed a piece of ordnance.

Plan for defence of the town

The houses of Port Elizabeth lay principally along the sands under a table-land. To the left of the town, the Baakens River, with its high banks, formed a natural obstacle to an enemy in that direction. To command the fordable mouth and the opposite bank of this stream, one gun was placed on the elevated plateau at Scorey’s Hotel. The eighth section, with its gun, occupied a barricade across the road near a toll, and the gardens, hedges and beach on the extreme right. The remaining sections, numbered from two to seven, occupied the intermediate space between Fort Frederick, above the Baakens River, and declining towards the Toll which was located between the future Russell and Albany Roads. The wagons from the neighbourhood, which had taken shelter in Port Elizabeth, were drawn up along the line between the guns on the table-land. In this manner, they fulfilled the role as an extemporised trench albeit above ground. Sections were also numbered from one to eight in order to correspond with the numbers allocated to the guns. The role of the Captain of each section was to lead his men to the gun with the number corresponding to his section. After that, he would spread his men in a line between the gun with the same number and the next gun. Surprisingly each Captain was only issued with two rounds of ammunition.

In accordance with the prevailing attitudes towards the black races, this motley militia with a melange of competencies, was openly considered more than capable of coping “with an immense array of Kaffirs”.

Notwithstanding this dismissive attitude, to provide for any emergency, an inner line was drawn up. This area, or citadel, encompassed the area at Market Square and the contiguous beach and harbour area. In the event of an attack, all the women and children in the town would be evacuated to this area. Should the outer defence line be breached, they would be evacuated by sea. In the event of being overwhelmed, the defenders in the outer defence perimeter could retreat to the inner defence line, rally and then unencumbered, they could endeavour to recover the lost ground if they were so capable.

The gunners were instructed in the use of the guns by two men of the Royal Artillery and notches were cut in the quoins or wedges, and on the platform to ensure the proper elevation for round or grape-shot. Being non-military personnel, implicit obedience was demanded of the gunners. They were cautioned that any action bordering on anarchy or confusion would certainly result in their defeat especially if the enemy was superior in number.

Prior to this plan for the defence of the town being drawn up, many of the inhabitants were on the eve of embarking and leaving the town. After the scheme of defence had been instituted, the residents felt so secure that they even secretly yearned for a Xhosa attack in order to prove their mettle against these “savages”.

An enemy demonised

All wars are said to bring out the worst in mankind and this war was no different. Moreover, the worst possible motives are imputed of one’s enemy actions whereas one’s motives are deemed to be as pure as driven snow. Listed below are some of these atrocities attributed by the white colonial population of their Xhosa counterparts. Whether any of them bear any relation to reality, one will never know. Alexander has listed several of the depraved and shameful deeds which allegedly formed part of their modus operandi.

The Xhosa attackers quickly gained a fearsome reputation and made no distinction between sectors of the white population. Whether they were English or Dutch, they were mercilessly slain whenever they fell into their hands, but they mercifully spared women and children. On the other hand, they were greatly admired for displaying great personal courage. When cornered, like the Japanese soldiers during WW2, they would fight until they had thrown their last assegai. What terrified the population was the rumour that the Xhosa would disembowel any whites that they caught rather than killing them outright.

A church at war

On the following Sunday, Alexander attended the local church, St. Mary’s at which the Rev. Francis McCleland – my great great-grandfather – delivered the sermon. Alexander found it strange to see an English congregation sitting in a church with the windows barricaded in case of attack and muskets piled in the corners. He reflected that “a frontier church ought always to be built with an eye to defence”.

Before he finally left Port Elizabeth for Graham’s Town, Alexander was a member of two or three courts martials. The charges in all cases either related to burghers who were insolent to their officers or refused to stand guard.

Thereafter Alexander set off for the front.

Return on 30th September 1835

During the war, James Edward Alexander was appointed as aide-de-camp to the Governor, Sir Benjamin D’Urban and accompanied him on his in loco inspection. Having appraised himself on the progress of the Frontier War, D’Urban would return to Port Elizabeth with Alexander accompanying him even though the route to the Cape in the days when the Van Stadens was a formidable obstacle, was via Uitenhage.

Together with D’Urban, Alexander would ride from Uitenhage to Port Elizabeth where they would spend an excellent three weeks in what Alexander refers to as “that good house of entertainment, Scorey’s Hotel”.

Alexander describes their arrival in the following terms. “On the arrival of the Governor, there was a grand illumination of the town. Salutes were fired and a round of dinners and balls was given by the hospitable and spirited inhabitants of this thriving sea-port”.

They had arrived at the tail-end of a “Mauritius hurricane”, as Alexander described it, which “had just visited Algoa Bay with irresistible force and ……………… had driven on shore and totally wrecked three merchant ships, whose anchors and cables were too light”.

Having personally experienced the difficulty of disembarking from ships at Port Elizabeth and the need to use the cumbersome surf-boats, the Governor was awakened to the need to obviate their usage. He proposed that surveys be performed for constructing a breakwater or a pier and for moorings south-east and north-west, the directions of the prevailing winds. He also envisaged the erection of a lighthouse at Point Recife – current day Cape Recife – which the inhabitants proposed naming after him. In addition, a beacon would be named after an officer of the Royal Engineers, Captain Selwyn, who had erected it.

The naming of the lighthouse rock became a grand affair. A huge party travelled along the beach and the parallel sand dunes by horseback and in wagons all the way to Cape Recife. The whole distance of nine miles was through virgin beach and sand as the town itself had not yet spread as far as Humewood. After the traditional “breaking of the bottle”, the clergyman of St Mary’s Church in Market Square, Rev. Francis McCleland, gave an impressive address. It was a perfect day for a traditional English picnic as the day was clear and fine. Flags were displayed, a piece of artillery was fired, tents were pitched on the beach and a handsome dejeune was laid out.

In Port Elizabeth, Alexander extolled the virtues of his daily bath in a hole of the rocks near the mouth of the Baakens River. Whether this method of bathing was used due to Scorey’s Hotel not being so equipped or whether as a means of relaxation, Alexander does not elaborate in his book.

When the pair could no longer justify their sojourn in Port Elizabeth, they set off on horseback to Cape Town via Uitenhage.

Source

Narrative of a Voyage of Observation among the Colonies of West Africa by James Edward Alexander (1837, Henry Colburn, London)

Excursions in Western Africa & Narrative of a Campaign in Kaffir-Land by Sir James Alexander (1840, Henry Colburn, London)