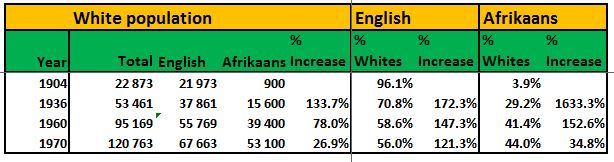

From only representing 3.9% of the white population in Port Elizabeth in 1904, the great influx of Afrikaners from the rural areas in the early part of the 20th century resulted in their share of the white population increasing to 29.2% in 1936 and 44% by 1970.

Over 70 years, Port Elizabeth was transformed from an English town into a South African town.

Main picture: Piet Retief Monument in Summerstrand

The Early Years

Some people point to Piet Retief and then claim that the Afrikaner must have had an influence on the early commercial life of Port Elizabeth. In fact, this is a fallacy as my earlier blog on Piet Retief makes clear. Using the pretext of this huge landholdings especially Strandfontein, he is held up as an early example of Afrikaner entrepreneurship during this era. The reality was vastly different. In most cases, due to his lackadaisical payment of rentals, he never became the owner of the property, or when he did, he sold it shortly thereafter. In fact, he probably never resided in Port Elizabeth itself but rather in Uitenhage for most of this period.

Dingaan invited Retief’s party to drink beer and witness a special performance by his soldiers. Not long after sitting down, Dingaan ordered his soldiers to capture Retief’s party and their coloured servants and to “kill the wizards”.

From this vantage point, it is surmised that although the bulk of Port Elizabeth was owned by Afrikaans boere prior to the arrival of the 1820 settlers, their economic influence was derisory as they were akin to subsistence farmers. Port Elizabeth required entrepreneurs such as Korsten and John Centlivres Chase to create an economy. In the same measure, it required a Jewish German immigrant by the name of Adolph Mosenthal to develop the wool export business. By assiduously nurturing the sheep breeds and Afrikaans farmers and by establishing relationships overseas, he developed the wool industry from a zero base to being a significant contributor to the economic development of Port Elizabeth. By the 1860s, Port Elizabeth had overtaken Cape Town as South Africa’s largest port primarily on the back of these exports.

As we are all well aware, British Settlers founded Port Elizabeth. Accordingly, it acquired a uniquely English character to the extent that it was claimed to be one of the most English towns in the Cape Colony. Consequently, by the turn of the century, with less than 3% of the population being Afrikaans speaking, English was the lingua franca, and the English way of life, the default way of life.

Railway Station in 1910

A family conundrum

In the early 1900s, my maternal grandfather, Harry St George Dix-Peek met an Afrikaans lass by the name of Caroline Frieda Nel. Where they met and how they met, is lost in the sands of time. Suffice to state that communication must have been problematic given that Harry did not understand Afrikaans at all and Caroline had been raised on a farm in the Middelburg District and had done her schooling in Dutch. Consequently, English was her fourth language after Afrikaans, Xhosa and Dutch. Apparently, her Xhosa was excellent but English was atrocious.

Harry & Caroline Dix-Peek

Nonetheless, they both spoke the language of love, a universal language. Caroline’s family, Afrikaans nationalists to the core and in the vanguard of rural Afrikaners migrating to the cities, settled in the English dominated Port Elizabeth. Apart from language difficulties, more intractable in an era when religion was pervasive and mandatory was which church they would attend. For Harry that was straightforward. As an Anglican, he had the choice of St Mary’s, Holy Trinity and St Paul’s, whichever was closest. For Caroline, it was not awkward at all. As there were no Afrikaans churches in Port Elizabeth, there was no church to attend. As an elegant compromise, they elected that their children should be raised neither as Anglicans nor as DRC but as Methodists. At that stage, the closest Wesylan Church was in Russell Road. With a choice of one, this church was selected.

On the 5th March 1911, when Harry was 23 years old, their oldest child, Redvers Percival Dix-Peek was born. This raised the next question. Most pertinent was their home language but also the issue of schooling. The latter issue had a simple resolution. As there were no Afrikaans Schools in Port Elizabeth, it would be Grey Junior School.

The rest of Caroline’s family remained farmers in the hinterland. Nevertheless, my grandparents’ house at 37 East Bourne Road, Port Elizabeth became a cheap and convenient holiday home for her siblings. This arrangement was bearable in an era where room size were not pokey and the expansive lounge / dining room could seat a King’s army for a meal. On the walls hung myriads of stuffed animal heads, mainly large animals such as buffaloes and elands, the bigger and more impressive the better.

37 East Bourne Road Port Elizabeth with granny and grandpa Dix-Peek on the verandah or should that be stoep?

During the late 1930s, the jovial situation took a negative turn. Afrikaner nationalism was rampant and feelings of victimhood and historical grievances festered everywhere. In order to confirm their pro-Nazi views, the Reunited Nationalist Party held a meeting in Feather Market Hall on the 1st July 1940 at which they called upon the Government to surrender to Germany. This vicious undercurrent exploded in the Dix-Peek household during WW2 when their four sons – my uncles – volunteered for military service. Apparently, the issue, which literally broke the camel’s back, was when the Afrikaans family would listen to the Nazi propaganda radio station, Radio Zeesen, while my uncles were fighting the Germans. This station, which broadcast on short wave from Zeesen in Germany, targeted South Africa, and especially its anti-British Afrikaners, promoting rebellion and insurrection.

A family feud ensued and the upcountry family was debarred from using the Dix-Peek house as free holiday accommodation. On the only occasion when I met one of my great aunts during the early 1960s, she lectured me on the reasons why South Africa should have remained neutral during WW2.

Radio Zeesen

The 20th century Afrikaner Influx

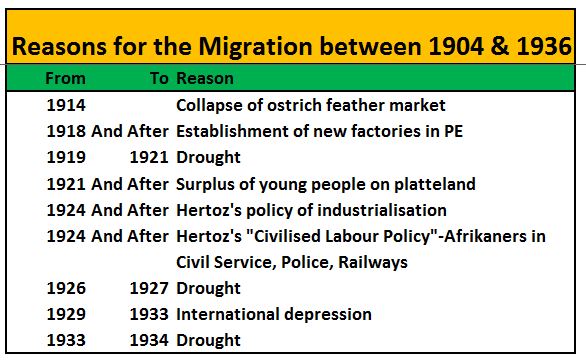

The urban influx in South Africa originated from two factors. The first was drought & depression during the 1930s but also the worldwide trend of urbanisation. With economic growth being centred on the urban areas, they were like a magnet with its positive pole being in the towns. The future of work was no longer the default of being a farmer but rather an artisan in the town. In 1911, the White urban-rural ratio in South Africa was 52:48 whereas in 1970, this had become 87:13. Undoubtedly, today, this ratio for Whites must be approaching the universal norm of 95:5.

The troubles bedevilling the Afrikaner after the Anglo Boer War were manifold. As if in slow motion, one could watch the calamity unfold as the scorched earth policy of the British destroyed the economic base of the Afrikaner nation. Defeated militarily and economically, for a nation where farming which had been the basis of their economic activity, but lacking educational facilities and professional training, they became impoverished. Lacking all the skills required of a modern economy, when they drifted into the towns and cities of South Africa. Furthermore, they lacked both the intellectual and monetary capital to partake in the economy as equals. The only work opportunities were the unskilled and semi-skilled occupations.

Map showing the earliest subdivisions of farms in Port Elizabeth-J.J. Redgrave

The last quarter of the 19th century had already witnessed a trend of Afrikaner migration to the urban areas. However, the magnitude was modest. The reason for this trend was the surging impoverishment of the rural areas. This tendency was so noticeable that for the first time, the term “Poor White” came into existence in South Africa. The decimation of game, the subdivision of farms into uneconomical plots, debts, drought and the rinderpest epidemic of 1896 accelerated that process of impoverishment. Economically it did not augur well for the Afrikaner.

Rinderpest in 1890

The watershed event that precipitated a crisis was the intentional destruction of 30,000 Boer homes during the Anglo Boer War. Usually it was not only the homes but also the livestock and all the agricultural implements.

En passant, it should be noted that Port Elizabeth also was home to a Boer Concentration Camp. It was situated on John Brown’s dam, today the grounds of the Old Grey Sports Club.

Like all low class societies throughout the world, to their wealthier fellow denizens they confirm the caricature of the incompetent worker. In spite of once being productive, energetic members of society, cast into an industrial and commercial world, they were treated as imbeciles and contemptible.

Boer Concentration Camp – Location Unknown

Extent of impoverishment

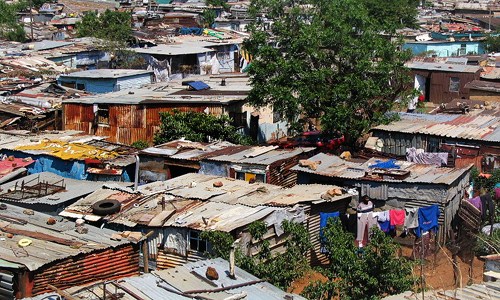

With no successful role models to emulate, they were forced to live in slum conditions in unattractive northern areas such as Korsten, North End, Sydenham and Sidwell. They had to live there in order to be close to the factories. In 1931, 3,710 Whites – mostly Afrikaners – and more than 10,000 blacks were living in Korsten. Conditions were appalling. Much like most townships were in 1990, there were no roads, no electricity, no street lights, no sanitation and no water.

According to Dr E.G Malherbe, a member of the Carnegie Commission, which was investigating the Poor White problem, there were 5,000 poor whites in Port Elizabeth in 1932, the greatest concentration of poor whites in South Africa.

The magnitude of the Afrikaner migration to Port Elizabeth can be understood when the period of 25 years from 1911 to 1936 is analysed.

Port Elizabeth’s socio-economic conditions in the late 1930s were the most unfavourable of all major urban centres in South Africa. Official statistics in 1937 regarding the slum areas of Port Elizabeth pointed out that 98% of the slum dwellers were part of the Afrikaners “trekkers” to Port Elizabeth from the platteland. According to a School Board Report of 1938, 53% of all pupils who attended the Piet Retief Primary School – chiefly attended by Afrikaans pupils – suffered from undernourishment and malnutrition.

In Sidwell, where a large percentage of the Afrikaner migrants resided, the housing conditions were absolutely shocking during the 1940s. Quoting from a report, it states, “No monkey can venture without risk along these stinking tracks, so-called streets of Sidwell. Streams of foul water in the streets run in all directions, in some cases streams 373 yards long. Wright Street is a green, slimy, stinking vlei. These so-called streets of Sidwell are really footpaths and tracks, which abound in potholes, craters and loose stones. They are soaked in and drenched with slop and kitchen water. They are the accumulated centres of dirt, dust and flies, a disgrace to a town such as Port Elizabeth.

By the 1960s, this grim picture of survival and triumph against the odds had been replaced with middle class suburbs much like the latter day transformation of Black townships such as Soweto.

For the Afrikaner, it must have been a steep learning curve from indigent unskilled labourer to businessman. From the first Dutch Reformed Church being established in 1907, now all suburbs have their own DRC congregation. The first Afrikaans medium primary school was established as late as 1930 and finally an Afrikaans High School was established in 1940. As the cherry on the top, when the local university was established in the 1960s, it was a dual medium institution.

Centenary of the first Great Trek

As part of the commemoration of the centenary of the Great Trek, a Voortrekker passed through Port Elizabeth on the 9th September 1939 en route to the Rand.

The centenary of the Great Trek was celebrated. Date of photo was 9th September 1938

Two wagons left Cape Town together and separated at George. After travelling down Cape Road to the Market Square, the wagon camped at the Piet Retief School, the venue for ceremonies in the evening. On the 11th November 1939, a monument to Retief and the Trekkers was unveiled at the school.

En passant

The process of integrating all the peoples of Port Elizabeth into an integrated city is ongoing. Like the Afrikaner in Port Elizabeth who felt slighted and alienated by not being accepted as an integral part of the community, so too are the black communities today. That process is germane to this discussion.

Notwithstanding that comment, one cannot appropriate current historical artefacts as Afrikaans or Black. That would be ahistorical. For example by renaming the Donkin Reserve, the Piet Retief or the Jacob Zuma Memorial Grounds would misrepresent historical fact. Rather create something new, a joint and shared artefact and cultural experience.

Strident articles in the 1970s by disaffected Afrikaners in Port Elizabeth, did nothing to advance their cause and none will now by similarly disaffected Black Nationalists.

A new century and another people follow in the same path as the Afrikaner a century ago in Port Elizabeth

By conflating Afrikaner concerns of the early 20th century and the Black concerns today is not to create a false equivalence. They are rooted in the same poisoned well of alienation, treatment as an unwanted intruder, disrespect and unflattering portraits painted of them as a nation. It is only the act of unconditional embrace of the other that such wounds can be healed and one’s conscience salved.

Sources

The Trek of the Afrikaner to Port Elizabeth by H.O. Terblanche

I wish relate a different Afrikaner experience from the one given here, to provide some balance to this article.

These are my own experiences, which admittedly were from a slightly later period: My mother was from Ermelo in the Transvaal, and trained as teacher at Normaal Kollege in Pretoria, where she met my father who was from Springfontein in the Free State, where his father owned the town bakery. He was a bit of an entrepreneur, having previously owned a cheese factory in Paterson near PE. Another son later owned the town supermarket in Senekal.

My father graduated from University of Pretoria as a doctor in 1953, and after a period in the army, bought a medical practice in the Langkloof – where I was born.

We moved to PE in 1965, when I was 5, and after a short while of living in Walmer, he bought a house in Hallack road, where I grew up. Before moving to PE I had never heard a word of English (that I was aware of), but remember learning the language in a few short months of exposure, through a neighbouring boy my age. We – my four siblings and I – attended Walmer Primary, which was dual medium, together with the Afrikaans children of other doctors/vets/professional people. We attended the Dutch Reformed Church in Cape Road, opposite the Provincial Hospital.

My upcountry family would rarely visit us in PE, although we made frequent family holiday trips to the Freestate.

Growing up as an Afrikaner in PE during the 1960’s (in my experience) being Afrikaans was not relevant, as we (my family) were all fully bilingual, and never noticed any language/cultural issues. In retrospect I probably suffered a degree of social discrimination from some (English) people, but it never registered with me, and equally I was very well treated by many English families I interacted with socially. I certainly never felt alienated or slighted – I would have laughed at any “Engelsman” who considered himself my “superior”!

While my siblings all attended Pearson High (an Afrikaans school then) I opted for Grey High (against my father’s wishes) – where I was the only Afrikaans boy in my year. I never actually aware of that, until a recent school reunion, when it was also pointed out that almost half of the boys at the school are now Afrikaners. (Not sure if that is actually true).

My parents were both from the era described by the author, and without any social, commercial or educational capital, they were able to Trek to the city, and thrive there.

Hi, I believe that the English / Afrikaans divide within South Africa has largely disappeared. It was a major issue in the early part of the 20th century and when I was going to school in the 1960s, the them-and-us attitude was still prevalent. I left PE in 1820, so I am not aware what the situation is today but certainly in Joburg there is very little animosity between the language groups.