Very few books, songs or photographs leave a profound impact upon anybody. Like bubble gum, most are enjoyed for a few moments and then spat out. Ironically I read this book about the devastating effects of racism whilst serving three months in the Army on the Zambian border. It was ironic for another reason too. Prior to reading this book, I was under the mistaken belief that the Jim Crow laws in the USA and Apartheid laws in South Africa benefitted my black brethren. Why did it have such a profound effect upon me?

Main picture: The modern equivalent of a 1960s issue: Blacks lives do matter

Musical awakening

Musically I had already experienced an epiphany that most music was junk with no long-term aesthetic value apart from a catchy melody. Pride of place in my record collection was no longer Neil Diamond or the Bee Gees but Grand Funk Live, Deep Purple, Jethro Tull and The Who. The more complex the melody and the arrangement, the more enduring the song was for me. It was John Lord of Deep Purple whose foray into classical music which intrigued me even more. Here was a keyboard player of the foremost rock band of the era composing a concerto in the style of a Beethoven composition. To this day, I still regard Movement 3 of the Concerto for Orchestra and Band as one of the greatest concertos ever.

The album Grand Funk Live might have been my musical awakening but the book Black like Me by John Howard Griffin which was to be my political awakening. Not that I overnight became a liberal but it created a mounting sense of unease which conflicted with my conservative conformity. The cognitive dissonance that it created conflated with my long view of history was that I came to realise that such racist policies and practices were unsustainable and in fact, immoral.

Jim Crow Laws and Apartheid

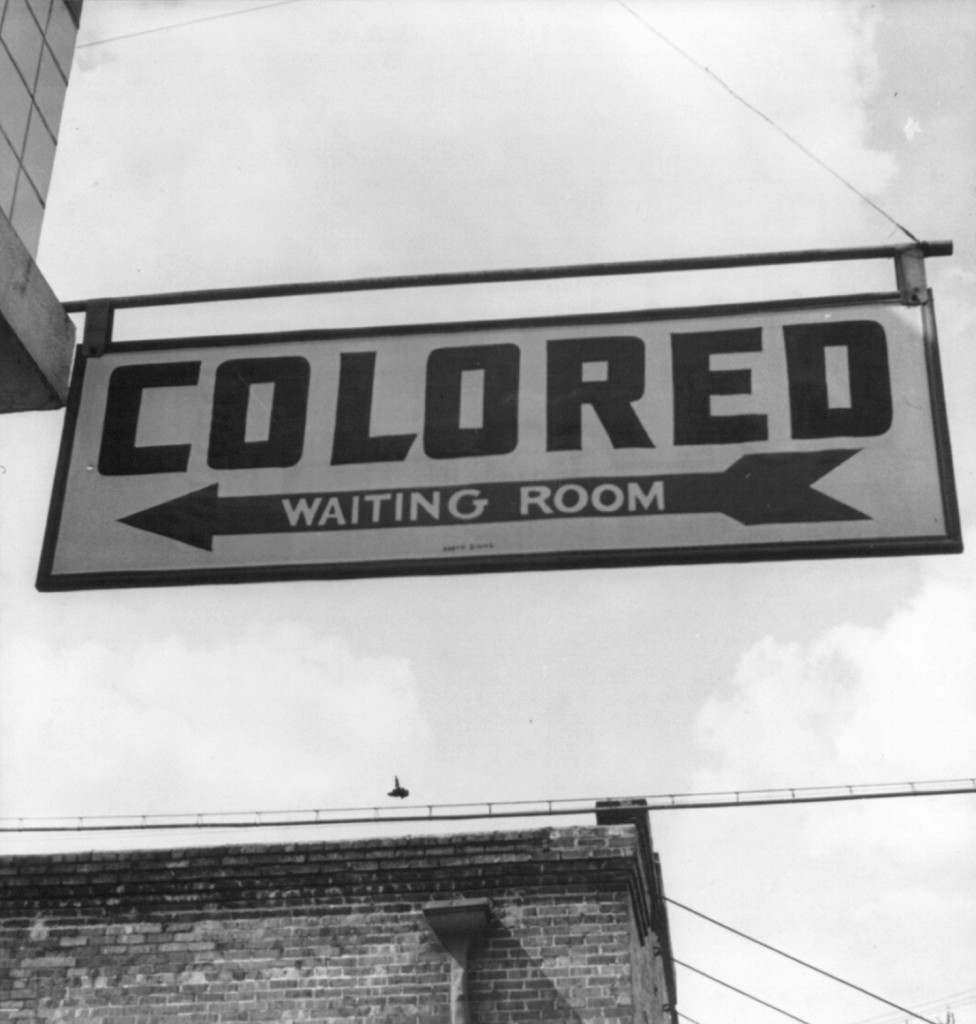

While South Africa had Apartheid, America had the Jim Crow Laws. What form did segregation and discrimination in America take? In the south it was de jure. Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. They mandated de jure racial segregation in all public facilities in states of the former Confederate States of America, starting in 1890 with a “separate but equal” status for African Americans. This body of law institutionalized a number of economic, educational, and social disadvantages.

The situation in the northern states was different. Whereas de jure segregation mainly applied to the Southern United States, while in the North segregation was generally de facto — patterns of housing segregation enforced by private covenants, bank lending practices, and job discrimination, including discriminatory labour practices.

Like in South Africa, conditions for African Americans were consistently inferior and underfunded compared to those available to white Americans.

Going to War

In mid-December 1978, I landed in Mpacha on the eastern tip of the Caprivi Strip opposite Zambia. Our aircraft was the venerable Flossie – as the Hercules was affectionately known. Being an Afrikaans Regiment – Regiment Uitenhage – I quickly ascertained who the other English speakers were. There were three. Based in Uitenhage, the Regiment drew its members from the surrounding areas – Uitenhage & Despatch. Being predominantly blue collar Afrikaners with little or no education, they mainly worked at the Volkswagen Vehicle Assembly Plant at Uitenhage or at the numerous railway workshops in the area.

The venerable Hercules now 50 years old, the same age as the book Black Like Me

In contrast to these functionally illiterate fellow soldiers, the three souties – the Afrikaners pejorative term for English speakers – all had post graduate qualifications. But that is where the similarity between us ceased. The first one I never saw again whereas the other, who was a reporter for an English newspaper, was a rabid socialist.

It was this short truculent individual who would lend me this seminal book – Black like Me. During the two week refresher course, there was no time to get sufficient sleep let alone read. Once we were assigned to operational duty, it was a different matter. This comprised a 5 day patrol which culminated in our forming a circle for all-round defence during the late afternoon. It was then that I would read a chapter while the enchanting African night descended upon us. After the strenuous patrol through the African bush weighed down by a 50kg pack, we were ferried back to camp in armour protected anti-landmine vehicles normally being Buffels. The next two days were spent in dugouts guarding the perimeter of the airfield. The schedule was 4 hours on and 8 hours off with the only mental stimulation was reading. In that regard, my fellow troepies made no connection.

Black like Me

John Howard Griffin posed a very poignant question when studying the issue of race relations in America during mid-20th century. “If a white man became a Negro in the Deep South, what adjustments would he have to make?” Instead of merely interviewing Negros as any other journalist would have done, Griffin’s audacious plan was to shave his head and to temporarily darken his skin by medical treatments and stain it in order to obtain the ultimate inside story on the state of race relations in parts of Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia as a faux black man. Griffin would find out at first-hand what it is like to be treated as a second-class citizen–or, as he says, as a tenth-class citizen.

As one book reviewer noted:

Griffin’s experiences take the daily evils of racism and thrust them in your face, just as they were thrust in his–the rudeness of the clerk when he tried to pay for a train ticket with a big bill; the difficulty he had in finding someone who would cash a traveller’s cheque for a Negro; the bus-driver who wouldn’t let any blacks off the bus to use the restrooms; the white man who followed him at night and threatened to mug him.

Only by adopting the skin colour of a black man was he able to understand how abominably Black Americans were treated. He was not even considered as a second class citizen but as he comments, “a tenth class citizen”. Wherever Griffin travelled in the South, he was met with blatant acts of racism. From sarcastic malice in comments, intentional slights togethet with the daily indignities of second class treatment, a mounting sense of unease arose within Griffin.

He was faced with the unpalatable reality that by treating Blacks as being different, they were not accorded separate but equal status; instead they were demeaned in a hateful manner on a daily basis

Another reviewer notes:

Even more interesting than these experiences was the way in which Griffin was allowed to converse with blacks and whites on racial matters. Understandably, blacks were highly suspicious of whites and were often inclined to play “the stereo-typed role of the ‘good Negro'” when around whites to survive in white southern society. As a “black” man, Griffin enjoyed a rare glimpse of how blacks really regarded segregation beyond the white propaganda. He also discovered the ways in which blacks assisted and supported each other against the perils of racism. In other cases, Griffin observed blacks who were ashamed of their race and who would denounce other blacks for their darker skin or shabby clothes. As a “black” man, Griffin also saw a side of whites that would otherwise be hidden if he had met them as a fellow white man. His experiences with whites while hitchhiking through Mississippi are particularly intriguing.

As Griffin’s mounting sense of unease grew, so did mine. The parallels between the Jim Crow Laws in America and Apartheid in South Africa were self-evident. In neither instance would race relations not be immune from its effects. Here was South Africa attempting to overcome communist insurgents by means of a hearts and minds policy with the express purpose of wooing the local inhabitants. This was wishful thinking. Of cardinal importance to achieving this goal would be to genuinely treat the members of the local populations with dignity and as equals.

The maxim “walk the talk” should have applied but immersed within a racist ideology, a sense of impending doom arose within me. The grave consequences of this ill-treatment of and disdain for the local population would be victory by Swapo however many battles the forces of the Nationalist Government won on the battlefield.

Epilogue

At a vital juncture in American history, John Howard Griffin had made a seminal contribution to the American Civil Rights Movement through the publication of his expose of the reality of black life. For many whites in the USA it was a rude awakening to the unpalatable reality of segregation that “separate but equal” meant that Blacks would be accorded a status as less than second class citizens.

Such epiphany was not America’s alone.

It was mine too – in far-away South Africa.

Sources:

Book: Black like Me by John Howard Griffin

Images: Wikipedia

I bought a paperback copy of BLACK LIKE ME when living in Durban in the late 60’s.

Was still at college at the time around 19 years old.

I seem to think that I have an E book version floating around.

Interesting article.

Many thanks

Tony