That evening, Monday 15th January 1934, was not going to be a good one for the ship from Osaka, Japan en route to Cape Town. An angry south-easter was gusting as this steamer left the protection of the recently completed Charl Malan Quay at 19:00. Unlike the days of the sailing ships, when the wind from this direction could be a death sentence for ships at anchor in the bay, the conversion to steam had long since tamed that menace. After exiting the harbour and entering the choppy waters of the Bay, the ship veered to starboard and headed for Cape Recife to meet its fate.

That day would also not be a good day for the newly-arrived destitute Jews from Nazi Germany. In effect the call by the Grey Shirts in the Feathermarket Hall to block the emigration of Jews to the Union, would constitute a death sentence to Jews trapped within the warped bigoted anti-Semitic world of Nazi Germany. But how would the stranded Japanese sailors fare in a race addled country far from home?

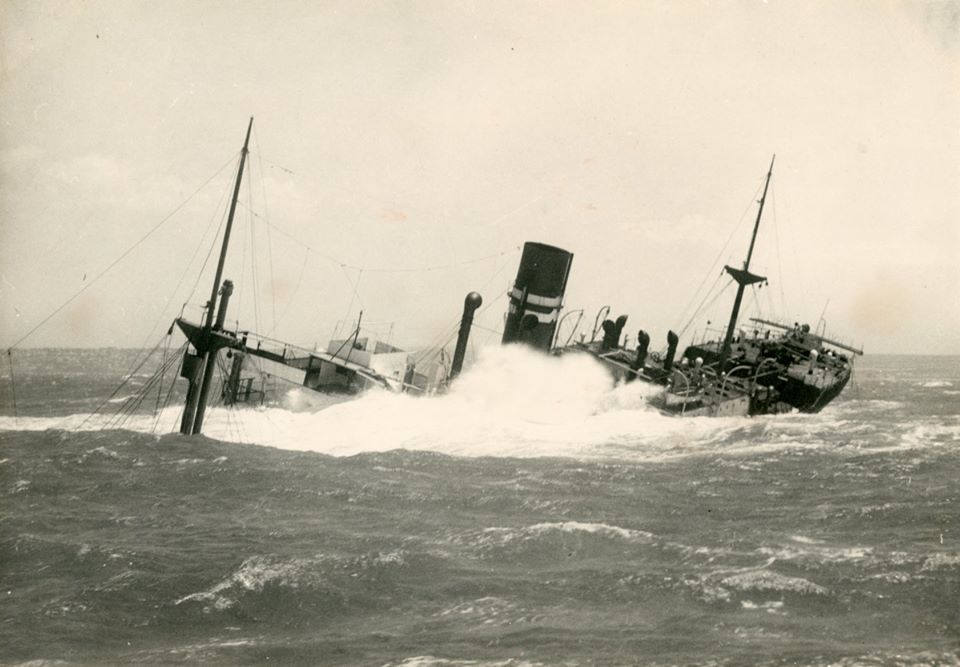

Main picture: The swansong of the Japanese merchantman, The Paris Maru

A century before when sand dunes still girdled the southern extremities of the hook shaped peninsular, great clouds of sea sand rose from the Driftsands and made a nuisance of themselves across town. Even strollers engaged in idle chit-chat in Main Street – or High Street as it was then known – complained at this confounded nuisance. With these dunes long since covered with exotic bushes and trees, no billowing clouds of dust were visible from the bridge of the Paris Maru that night.

The Bay was alive with white horses. They rode the crests of the waves, galloping after those in front of them, never seeming to catch them but would explode into shards of foam which were re-incarnated into splendid white horses.

Then the lights of the Pollock Hotel – later renamed the Summerstrand Hotel – came into view on their starboard side. Almost instantaneously the gut-wrenching high-pitched falsetto note of steel against immoveable rock screeched out as the vessel lurched to a halt. None of the crew had registered that Roman Rock, previously known as Dispatch Rock, was located several hundred metres offshore. For this inattentiveness, they were to pay a grave price.

Instinctively, the Captain of this ill-fated vessel, attempted to regain the harbour. The Paris Maru managed to back away and proceed some distance under her own steam. But it was not to be. With the bow submerged and the stern and propeller raised into the air, she could only drift in the turbulent sea. The angry seas, eager to claim another victim to add to its grim grand total for the year, broke furiously over the sunken bow. A reading of the water level in the ruptured front hold revealed that it held five feet of water. A subsequent sounding 20 minutes later, revealed that the water level had escalated to between 15 and twenty feet.

Danger now confronted all of those below decks. The gaping hole torn in her side, caused her to list dangerously to port. Aboard the ship, tight discipline was maintained. Innate Japanese obedience informed the 68 Japanese sailors to herd together on the sloping afterdeck to await their fate. Without a remote chance of the crew stemming the ingress of water into the hold, the hopelessness of the situation was manifest to all and sundry.

With the tugs Lady Elizabeth and the James Searle as well as the SS City of Hereford in attendance, the Paris Maru drifted helplessly towards the northeast corner of the Bay. What little hope there remained of towing her to safety evaporated when her submerged bow rammed into a sand bank only eight or nine fathoms under water. By this time the engines of the Paris Maru had ceased to function, and the lights had failed. Rescue work now had to proceed by the light of flashlights which poked conical holes into the Stygian darkness.

While this drama played out at sea that night, another spectacle unfolded in the Feather Market Hall. Maybe this meeting was not as immediately life-threatening, but its long-term implications were one of foreboding. This gathering was to protest against allowing undesirable immigrants – a cypher for Jews – into the country. This turned out to be basically a rancorous outburst of anti-Semitism and it was immediately followed by articles in the ”Herald” and sermons in the churches warning against “panic” and this “alien growth” among Port Elizabeth’s citizens. Like most of the Western world, South Africa was the recipient of Jewish refugees from Nazi-controlled Germany. Amongst that flotsam would be two escapees from Germany, our neighbours in the 1950s and 60s, Erna & Arthur Siesel. One cannot imagine what their ultimate fate would have been if they had been unable to escape from the clutches of his barbaric regime. Two weeks later, on the 29th, the PE Division of the S.A. Grey-shirts, a pro-Nazi organisation, organised a meeting in the Feather Market Hall at which a fight ensued. With my maternal grandmother being Afrikaans and her siblings joining the pro-Nazi Ossewa Brandwag, this would culminate in a fracture in the family.

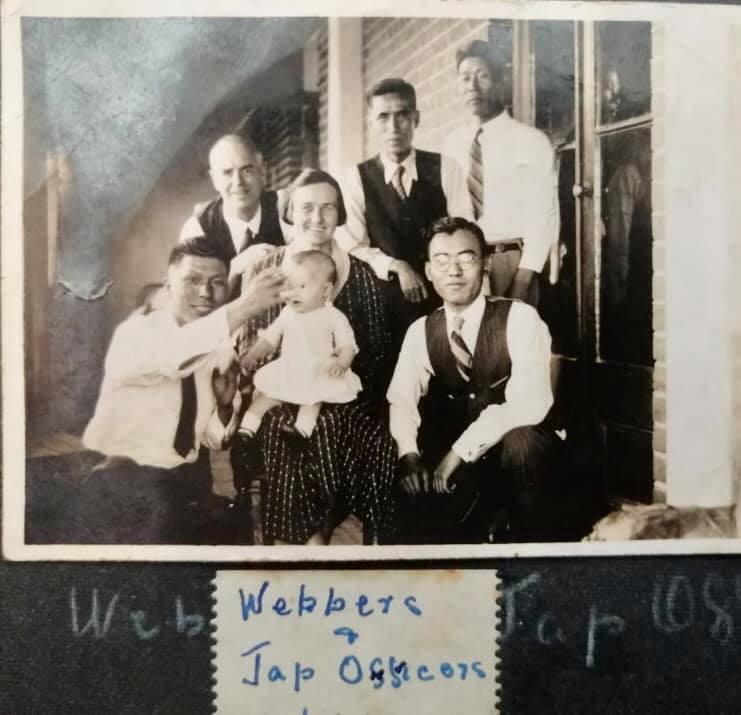

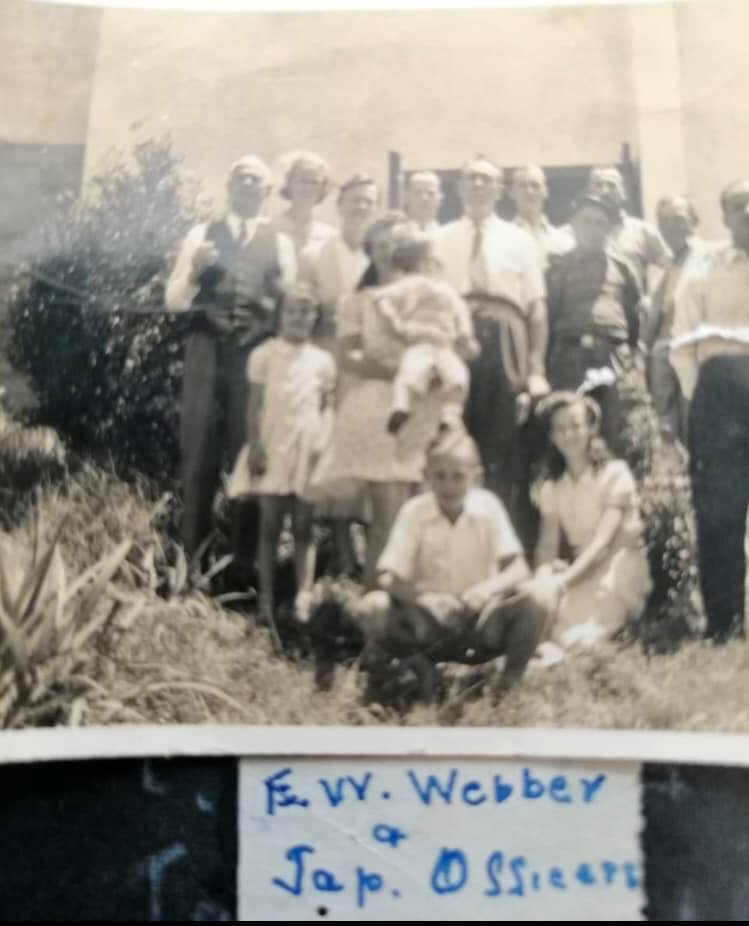

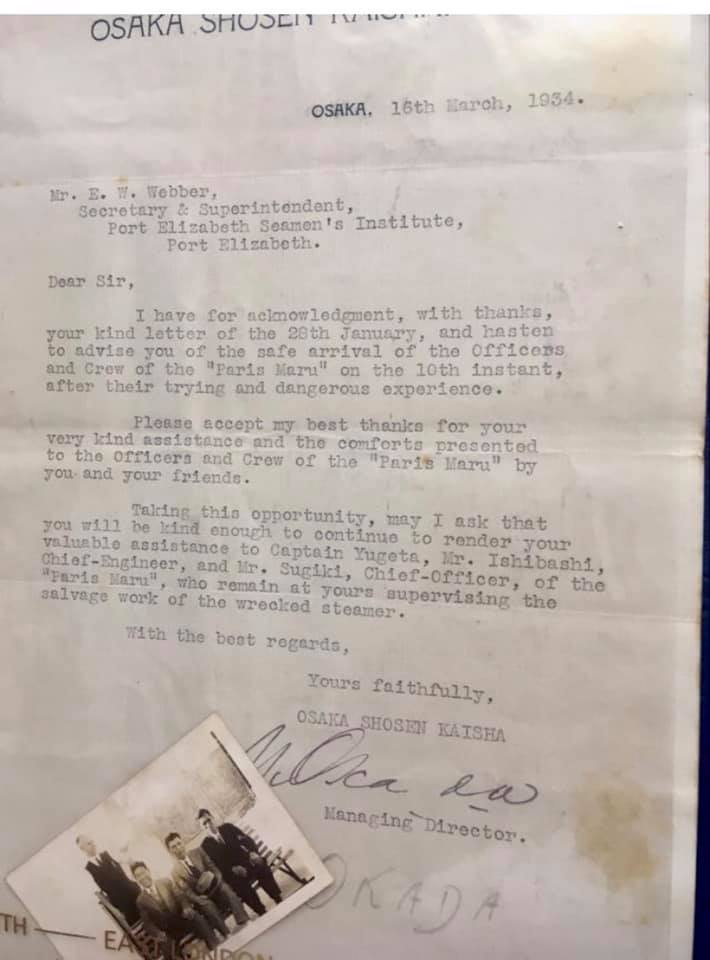

While bigotry was being idolized in the Feather Market Hall, human kindness was being displayed by Mr. Webber, manager of the Seaman’s Institute, who arranged accommodation for the Japanese crew rescued from the sinking ship. But that is getting ahead of the story.

At 22:00, an order in Japanese rang out from the bridge. Without any sense of panic or inconsiderate behaviour such as queue jumping, the crew smartly made ready to depart. Shortly after the announcement, the first batch to leave the Paris Maru, 24 in all, took their seats and the lifeboat was launched. The tug Ulundi picked up the shipwrecked sailors and the lifeboat was cast adrift.

Meanwhile the Paris Maru was burrowing deeper into the angry seas and soon the entire forepart of the vessel was awash. By now the vessel was off the coast at North End beach, a favourite swimming area in those days with its golden beaches stretching from Victoria Quay to the beach at New Brighton. It was only later in the 1970s that the beach was used for the Settlers freeway.

At intervals, two more boats were launched, no less than 32 of the crew crowded onto one small dinghy, which safely weathered the swell and was picked up by the tug the Lady Elizabeth. This rescue effort continued until 2:00 on Tuesday day morning. At this point only four men remained on board, the skipper, Captain Jugeta, the Second Officer and two quartermasters.

In one desperate last-minute endeavour to stave off complete disaster, the tugs Lady Elizabeth and James Searle managed to get lines aboard the Paris Maru. This experimental exercise was solely to ascertain whether they could haul her off the sand bank into which the bow was embedded. This effort, however, proved the futility of such an undertaking, whereupon the tugs cast off and stood by once more. It soon became apparent that it would be a futile risk for the handful of men to remain on board. By now the stern and afterdeck were high out of the water while the remainder of the vessel canted steeply to port, being entirely submerged.

The die was cast. The ship had to be abandoned before unnecessary loss of life occurred. At 3am, the Lady Elizabeth launched a lifeboat which made a perilous journey across to the ship’s starboard side. Abandonment was by now a risky venture. A rope was thrown overboard and attached to a railing. One by one, the officers with much trepidation slid down the precariously swaying rope to their safety in the lifeboat bobbing in the water below. The last to leave was Captain Jugeta who continually expressed his reluctance to abandon his vessel.

Finito or more correctly 完成した

Aboard the Lady Elizabeth was an anxious Port Captain, Capt. Dent who had spent an uncomfortable vigil aboard the Lady Elizabeth. At 5am, he made an inspection trip across to the floundering vessel. By now all the forward holds – 1, 2 & 3 – as well as the stokehold and the engine room were completely flooded. Only two hatches – Nos. 4 & 5 – in the aft part of the ship, remained dry. By now it was quite evident that this was a temporary respite and that their escape from flooding was no longer possible and that it was only a matter of time before the whole steamer was submerged.

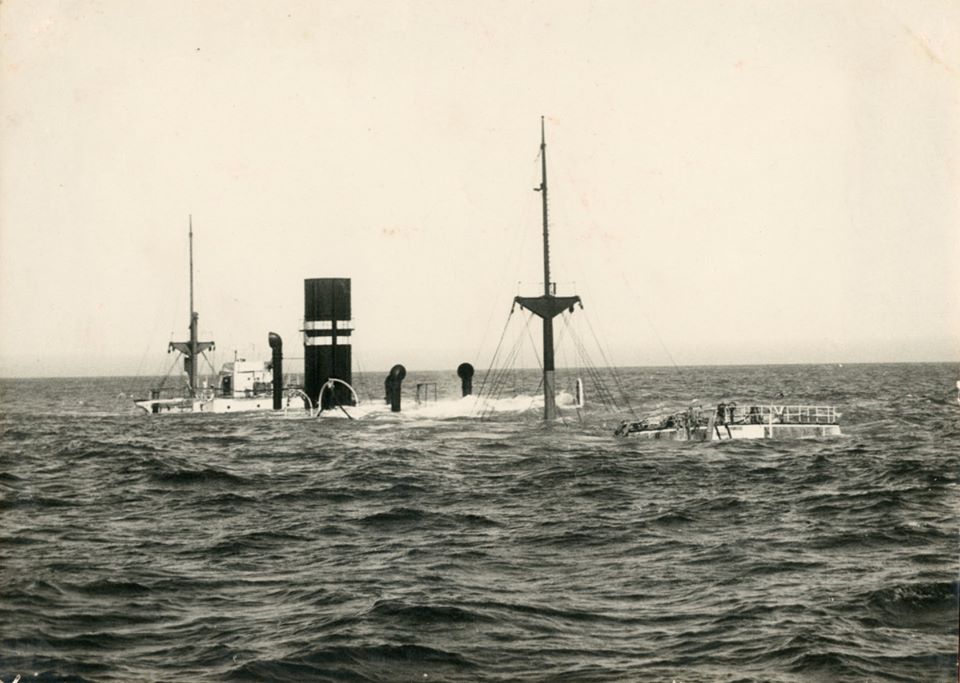

Capt. Dent provided the following graphic account of the vessel’s final moments as follows: “At about 2:45 she seemed to straighten up a bit and held that way for about ten minutes. Then she gradually seemed to be going straight down, and at 3 o’clock the air pressure in the holds gave way and she blew like a fountain for about 3 minutes. In about five minutes, the steamer had settled down entirely on an even keel, leaving the funnel, two masts and what appears to be the compass stand on top of the chartroom above the water”.

Finally, the Paris Maru sank about an hour before high water and at full tide it was estimated that there was 13 feet of water over her hull.

As the Paris Maru represented a threat to shipping in the roadstead, it underwent the final iniquity of being blown up in order to flatten her out. Today in her watery grave she is more than a collection of rusting steel and cargo. As an artificial reef, she has attracted many species of fish as protected accommodation conferring a boon for deep sea divers.

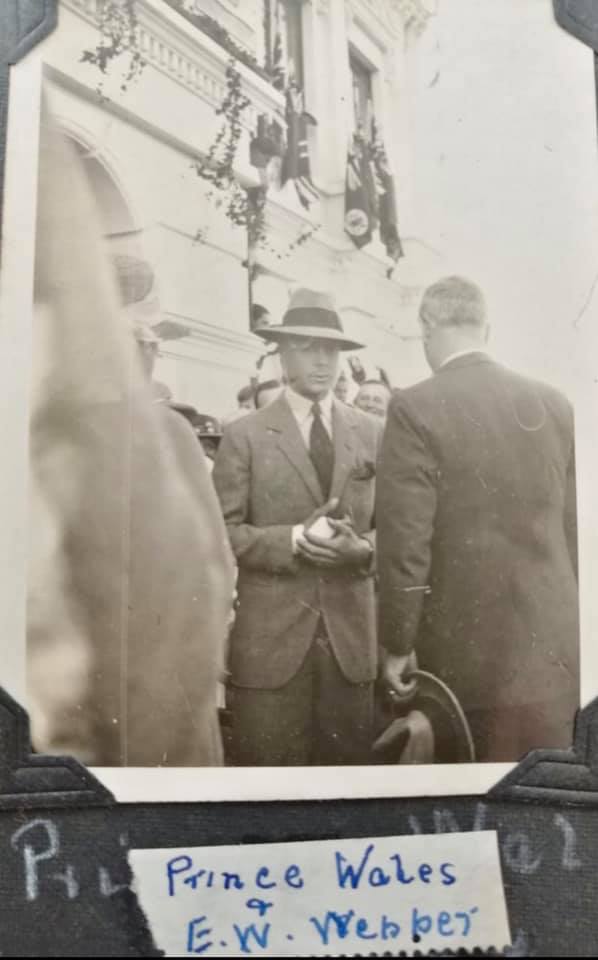

It was a generous and humble Ernest Webber and his wife, Evelina, who would come to the rescue of these Japanese seamen. Showing none of the bigotry of some of his fellow South Africans, Ernest took them under his wing and provided them with a roof over their heads for three months at the Seaman’s Institute where he was the manager until such time as they could be repatriated to Japan.

DETAILS ON RECEIVING THE JAPANESE FAN

Japanese ship Paris Maru sank off Port Elizabeth after hitting the Roman Rock in January 1934.

The Captain and the crew were put up at the Seaman’s Institute (now known as the South End Museum).

The full crew stayed for 2 weeks and the Captain, Chief Engineer and one other officer (forgotten which one) stayed for 3 months, until enquiries were finished as to why the ship sank.

From time to time whenever one of the crew were in PE on different ships, they would visit the Institute and my mom and dad were given gifts from Japan, and each one of the family were given small gifts such as the fan.

Dad [Mr Webber] was Secretary – Superintendent of the Seamen’s Institute from 1st June 1930 until 31st December 1945.

According to Terrence Gouws “Apparently baseball in the PE area was introduced by Japanese sailors on board the Paris Manu, which marooned in PE. The sailors aboard stayed in Port Elizabeth for 3 months, who had baseball equipment on board and played against Americans at local companies at the Westbourne Oval, in 1934”. I am unable to confirm his comments. But if they are indeed true, it would be a fitting epitaph to the Paris Maru in a multitude of ways: creating an undersea Eden, the introduction of baseball and shaming the bigots in society by extending a courtesy to distraught non-white sailors

Sources

Port Elizabeth: A Social Chronicle to the end of 1945 by Margaret Harradine (2004, Historical Society of Port Elizabeth, Port Elizabeth)

The Bay of Lost Cargoes: The Shipwrecks of Algoa Bay and St. Francis Bay on the East Coast of South Africa (2005, Xpress Print and Copy, Port Elizabeth)

Japanese Steamer Sinks in Bay (1934, January 16th, Eastern Province Herald)

Photos of Webber family and relevant artifacts courtesy of Aubrey Coldrey

http://archiver.rootsweb.ancestry.com/th/read/SOUTH-AFRICA-EASTERN-CAPE/2005-10/1128968989

Hi there, apparently baseball in the PE area was introduced by Japanese sailors on board the Paris Manu, which marooned in PE.The sailors aboard stayed in Port Elizabeth for 3 months, who had baseball equipment on board and played against Americans at local company’s at the Westbourne Oval, in 1934. Which companies were this and is this the beginnings of baseball in the PE area?

Hi Terrence

I cannot confirm anything about the sailors being involved with baseball in PE but what I found out about the Paris Maru I have now included in myprevously rather modest blog on her sinking. So there was some positive consequence of you query

Dean McCleland

deanm@orangedotdesigns.co.za

082-801-5446