For numerous reasons, Port Elizabeth was last in the queue to receive a harbour. From the early clamouring in the 1830s, it would be another century before the first harbour was commissioned.

As the Harbour Supplement to the Eastern Province Herald dated 28th October 1933 stated, “

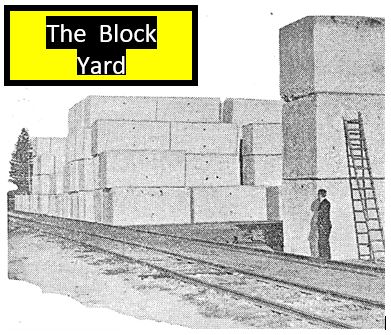

Building a harbour without concrete blocks would be like making bricks without straw. So, the blockyard is the foundation, as it were, of the work.”

This blog is an article from that supplement.

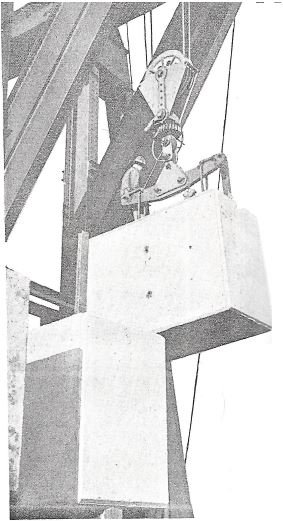

Main picture: The Titan crane laying a block on the breakwater

Almost lost to public notice, tucked obscurely beneath the Humewood Road embankment. lies the very pulse, the mainspring of the work of building the harbour – the concrete block yards. Through their never-resting, clockwork system streams about 55 per cent of the material of which the harbour is being made in the form of mass concrete. Serious delay in the yards and consequent slackening off of the supply of blocks would throw the whole of the harbour building operations out of gear, so that the work here is kept going, day in and day out (excluding Sundays) in rain or sunshine from daybreak until often long after the street lights have been turned on.

Not only do the yards turn out blocks, but they also supply tons of liquid mass concrete, which is absorbed in huge quantities by various parts of the harbour works from the blockyard concrete mixers, it is conveyed direct by train to the scene of operations and emptied into “box moulds”, where it is allowed to set as a permanent part of the structure. This type of work takes about a tenth part of the concrete passing from the yards.

Taking a panoramic view of the place, one finds that the mixing process starts with the charging of a cocopan with a quantity of sand. Next the cocopan runs beneath a stone crusher (of which there are three) to be filled with crushed stone. It then gravitates to a concrete mixer (of which there are also three) over a hundred yards distant, where its contents are emptied into the mixing drum together with a sack of cement. The mixture having been thoroughly churned, it is poured by the mixer into another cocopan which also gravitates on to one of several long, elevated platforms on either side of which the block moulds are set.

Each mould is filled. in turn, and then left for the concrete to set. Five days later, the mould having been removed and the block faced and trued up, it is ready for one of the pair of huge Goliath cranes serving the yards to take it up and place it on a truck for transport to the “waiting” stack, where it is left to “season” for at least six weeks before use.

Some idea of the magnitude of the work at the yards will be obtained from the fact that the output of concrete, in the form both of blocks and liquid concrete, since the commencement of the harbour totals more than 750,000 cubic yards sufficient to lay a road 12 feet wide and six inches deep from the City to north of Pretoria in a direct line. The monthly order for cement is 20,000 bags, and the Chelsea convict quarries supply two train loads of uncrushed stone daily. Fortunately sand is easily obtainable from the sea shore directly below the yards, and one small train spends its days, running by a zig-zag route to overcome the gradient. between the beach and the sand dump at the highest point of the yards.

When making a round of the yards. one is forcibly struck with the clever manner in which the fullest possible use is made of the power available from gravitation. At the highest point of operations one finds a row of stone laden trucks drawn up at the mouths of the crushers. Running down unaided from the sand dump. a cocopan service is filled with stone beneath the crushers. The pans then once more run down a gradient to the concrete mixers. At the same time cement is precipitated from the store sheds down a gentle slope to the mixers. Below the mixers waits another set or cocopans. and again gravitation is employed to carry them down to the platforms from which the moulds are filled. The whole of the cocopan journey for one load covering over a quarter of a mile of line, requires little more energy than an occasional shove by a native. The empty pans have then, of course, to be pushed back to the highest point, but that is quick comparatively light work.

Taking the process from its initial stages, one finds that the cement is run from the store and stacked at the head of the concrete mixers. In the meantime a cocopan is pushed up to the sand dump where a measure of sand, equal to three bags of cement, is tipped into it. Then off it slides to the stone crusher whose vicious jaws cooled by a constant water spray fill it with crushed stone. It is then sent swinging away down a long fairly steep decline to the head of the mixers.

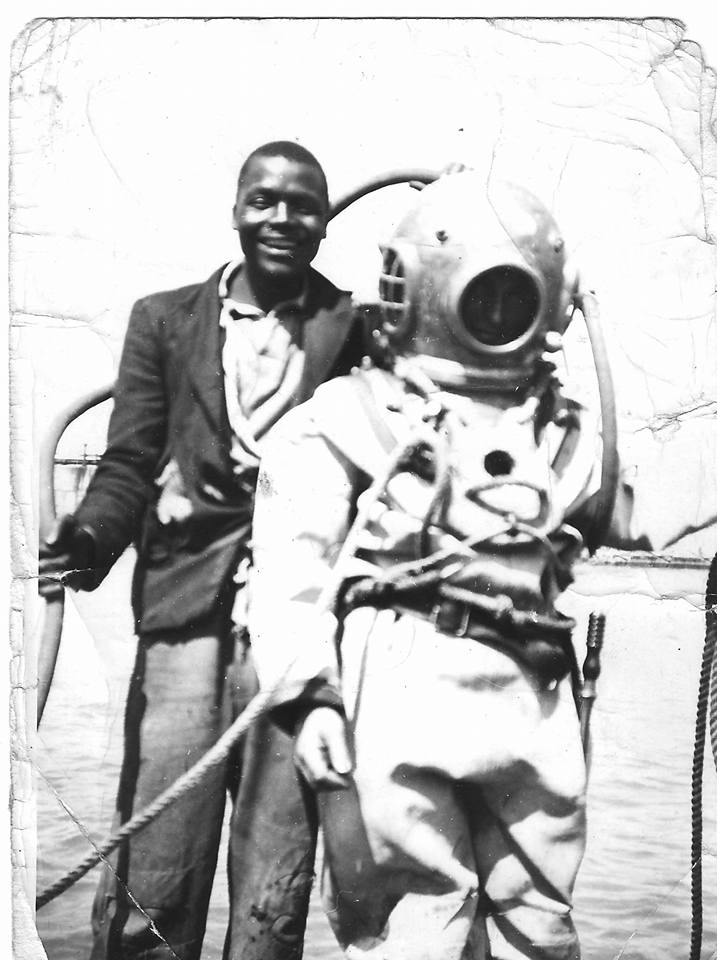

Here it is received by several natives, one of whom keeps in touch with the man in charge of the mixer by· means of hammer blows on a steel pillar. Incidentally, they use their own specialised Morse code. On getting the O.K. from the man below, they tip the sand and stone into the mixing drum, together with a bag of cement, giving an approximate mixture of six stone, three sand and one cement. Another man releases a stream of water – experience has taught him just how much is necessary – into the mixing drum which revolves for half a minute under electric power and then discharges into a cocopan below. Propelled by natives, this pan sets off to the platforms from which it is emptied into the waiting moulds.

The stone crushers, with their gigantic capacity for chunks of hard, untrimmed rock, are fascinating to watch in action. Straight from the top of the trucks, the natives hurl the weighty pieces directly into the mouth or the crusher. There is just a solid thud; not even the hint of a judder; the machinery hums on without any decrease in speed, and to the accompaniment of loud, crisp crunchings, finely shattered stone streams from the chute below. Each crusher is driven by a 60 h.p. electric motor.

Three sizes of block are turned out – 40-ton, 15-ton and 5-ton. The first and last are always rectangular and of regular dimensions, but the 15-ton type is made in about a dozen different shapes, sloping faces being used to secure extra strong binding in wall construction where these are used instead of the largest type. The 40-ton blocks have been used almost exclusively for the south arm, while 15 tonners are being used in the north arm. The smallest type is always left rough and it is used purely for dumping.

the breakwater

The block moulds are heavy, collapsible wooden structures firmly bolted up when erected. Before they are filled, they are coated internally with oil, and “Lewis pins” and “Dolley boxes” which leave the holes through the blocks for lifting purposes, are fixed in position. Every precaution has to be taken to assure that the mould is set up perfectly “square” or the block will be useless for building, since each block has to fit like a piece in a jig-saw puzzle. As soon as the concrete is sufficiently set, the mould is released and removed, and the Lewis pins extracted, for plasterers to face up and square off the rough sides and top. The filling of a 15-ton mould requires nine cocopan loads and occupies on an average from 12 to 15 minutes. The figures for the other sizes are proportionate.

The first men to start work in the yards in the morning are the crane attendants, who have to get up steam, and put their machines in trim for a hard, non stop day. These cranes, which were made in Britain in 1902, were brought here from Simonstown over ten years ago, and have given excellent ·service. Except for parts required here and there at intervals, they have proved exceptionally trouble free and reliable. They travel on rails parallel with Humewood Road for a distance or several hundred yards. Each has a lift capacity of 40 tons.

A well-devised method is employed for taking liquid concrete in mass from the yards to its billet. From the mixers the concrete is taken in cocopans to a special loading platform, where it is tipped into mechanical “boxes” with trap bottoms, standing on trucks, which are then drawn by a small engine to the harbour works. At the concrete’s destination a crane raises the boxes and suspends them over the built-up “box mould.” and the releasing of a catch opens the trap bottom of the container.

One cannot but praise the cocopan system in the yards. Alterations and modifications during ten years of use have brought it as nearly as possible to a state of perfect efficiency. The loaded pans always travel on level or falling grades and in most cases, there are separate return lines for the empty vehicles. At points where the pans have to stop, such as at the stone crushers after leaving the sand dump, the lines rise slightly-just sufficiently to bring the pan to a stop conveniently . An easy push sends it on its way down the next slope again. It has been calculated that each pan covers on an average between 10 and 14 miles a day. It takes only a moment’s thought to realise the tremendous amount of labour and energy that is saved in the manner described.

Unbending system keeps the work in the yard always up to standard. There is neither hurry nor slacking, as each man has his particular job-and does it. Each takes his place like a cog in a machine. The result is· that accidents are very rare-which is tribute to the Harbour Engineer and his staff in view· of the fact that there are over 200 men engaged amid constant train and cocopan traffic, and with heavy machinery. In case of accidents however, two fully qualified first aid men are always instantly available, and the necessary temporary dressings are kept handy at the yard office. Under the ever-watchful eye of the able foreman of the yards, Mr. R. Nel, perfect harmony reigns all day and every day.

The rough figures of output since the harbour was commenced are as follows:

- 40-ton blocks, 17,500

- 15-ton blocks, 3,500.

- 5-ton block 7,300.

- liquid concrete:

- 85,000 cubic yards on the breakwater and

- 8,000 cubic yards on the north quay

Practically all the cement used is produced in the Eastern Province These are the returns after ten years’ work, but the rate of work has been constantly increasing and, it is estimated that by the time the Harbour is completed, the figure will have been at least doubled.

Source

Eastern Province Herald Harbour Supplement, October 28, 1933