From a pristine lagoon in 1820 to an industtrial area in forty years, is how long it took to destroy this once virgin wilderness. Unlike the Settlers, the previous inhabitants of this area, the Khoisan, without any discernible desire at building permanent structures, left no detectable evidence of their presence in the area over eons.

As my blog entitled “Port Elizabeth of Yore: What Happened to the Baakens Lagoon? deals with the why and how the lagoon was reclaimed, instead this blog will focus on the conversion of this normally placid waterway and bush covered hill into the epicentre of industrial development within the restricted confines of the valley floor.

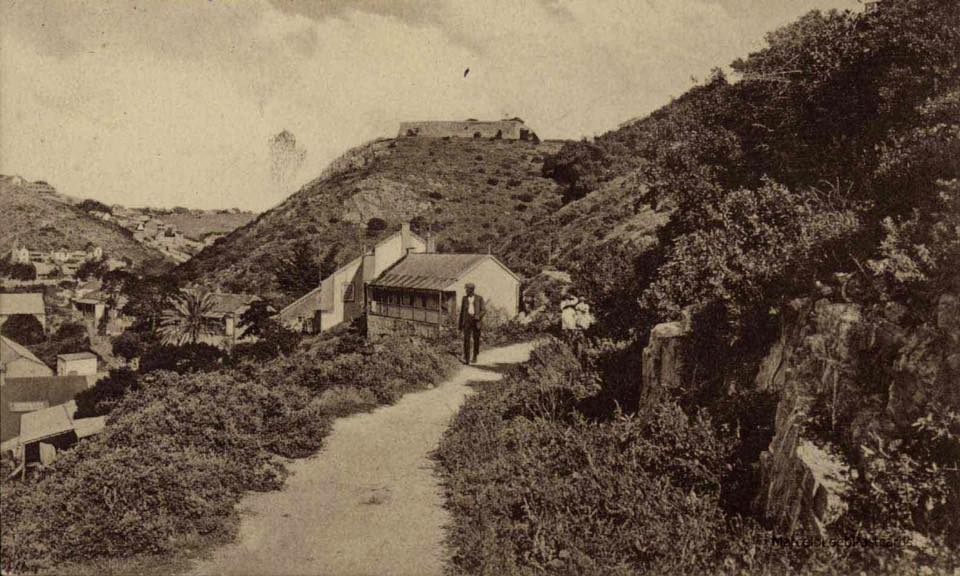

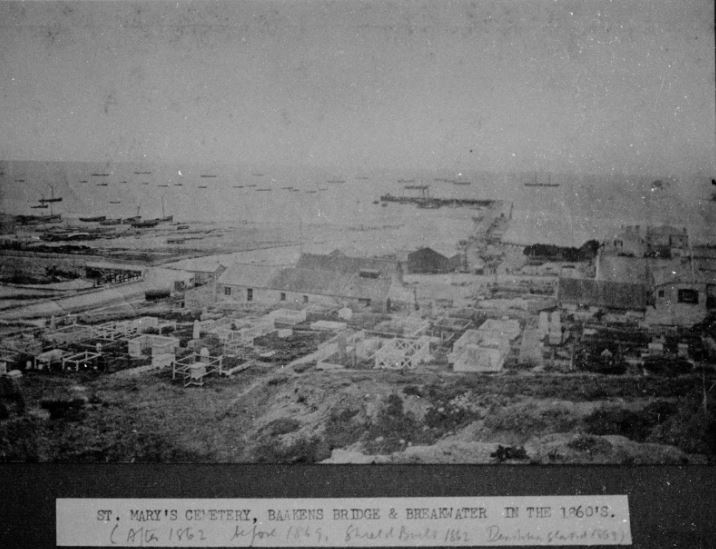

Main picture: The bridge across the Baakens in 1866 before the flood showing the lagoon [Redgrave]

The First Inhabitants

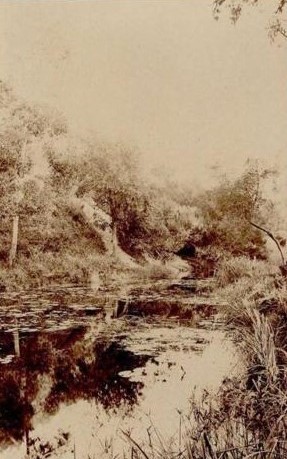

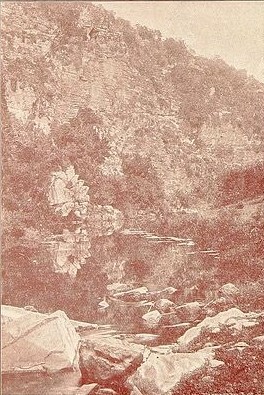

The Baakens’ valley, particularly the river mouth area has an interesting history. When the white man first landed on the shores of Algoa Bay, he found a river, the lower reaches of which formed a large sparkling lagoon surrounded by lush vegetation.

In spite of occupying the Cape in 1652, the Dutch were not the first residents of the Baakens Valley as they had been preceded by the Khoisan coastal dwellers who had originally hunted the wild game and gathered food from the prolific vegetation. While there are no physical remains of their presence in the Valley, there are documented reports of their bartering and conflict with the Dutch at the mouth of the river.

It was the freshwater from the Baakens River and the sheltered bay that attracted the sailors to first use Algoa Bay. In 1752 a beacon – a “baaken” in Afrikaans – was placed near the mouth of this river by Ensign Beutler, who was surveying the area for the Dutch East India Company. Evidence of this has been found in a 1789 Dutch map, indicating the “Baakjes Fonteyn” – the word fonteyn is more indicative its size than the word river – which they claimed rights to with a beacon on the prominent cliffs. Sailors and explorers soon began to identify the river with the beacon, and it became known as the Baakens River.

The first permanent inhabitants of Algoa Bay, as Port Elizabeth was known in those pre-Settler days, were the trekboers. These were independent-minded Dutchmen who ventured over the eastern border of the Cape Colony at Swellendam. In the mid nineteenth century, they were granted farms. By 1776 Theunis Botha had settled at Buffelsfontein, Thomas Ignatius Ferreira at Papenkuilsfontein, Willem van Staden at Coega, A. van Rooyen at Zwartkops Rivierwagendrif, Daniel Kuun at Seaview, Johannes Potgieter at Welbedacht [later called Walmer] and Gerrit Scheppers at Uitenhage.

In 1799 the first British troops landed and immediately took possession of the Lower Baakens. They erected fortifications on the current site of Fort Frederick and a wooden blockhouse near the drift across the Baakens near to its mouth. Their purpose was to protect them from possible Xhosa incursions and more imprtantly to prevent the French from providing logistical support to the rebellious Trekboers at Graaff Reinet who would shortly declare a short-lived independent republic

It was then the turn of the British settlers whose arrival would herald the most profound change. The first permanent resident in the Baakens valley was John James Berry who was granted the eponymous farm Baakens River Farm in 1819. Unlike the other farms in the Baakens, this farm was located much further up the river and encompassed the area from Glen Hurd through to Sunridge Park. Apparently his sons, Richard John and Matthew were personalities in their own right. What actually is meant by that, cannot be ascertained but one presumes that it indicates that they were adventurous or exuberant and rambuctuous by nature. In 1826, the farm passed to 1820 Settler, John Parkin. This farm was extensive by today’s standards as it encompassed the future suburbs of Newton Park, Sunridge Park, Fernglen as well as Fairview.

In the lower reaches of the river, a huge piece of land, later known as Rufane Vale was granted to Captain Moresby, captain of the HMS Menai, in July 1820 in gratitude for assisting with the landing of the Settlers. In addition, an erf facing the sea was also granted to him. A house, to be named Markham House, was constructed on it. In 1823, both of Moresby’s properties were purchased by Richard Hunt who had established a hotel in Markham House. In 1828, when Hunt was declared insolvent, the hotel passed to James Scorey and the valley land to Jonathan Board, a carpenter and builder.

By 1829, there were two houses in the Valley, Baakens River House near the bottom of Brickmaker’s Kloof and another nearer the lagoon.

Probably the first of many factories and businesses established in the valley was a woolwashery established by Handfield which is claimed to be the first to be erected by 1858. As his residence was in the Settler’s Park area, one can presume that he established his woolwashery there. This might have represented progress but it came at a cost viz degradation of the environ-ment. The wax or lanolin produced by the sheep while having useful properties, it also polluted the sparking water of the slow flowing Baakens River making it unfit for animals or humans. Once further woolwasheries were established downstream in Rufane Vale and Baakens Street respectively, the water quality must have become totally unacceptable.

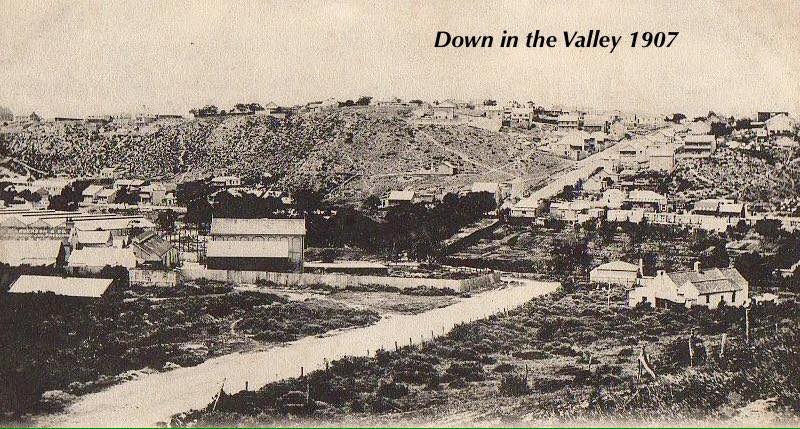

Industrial development in the Valley

The industrial area in the town was established in Baakens Valley. The reason for this was that most industrial process required water. As a consequence this area became the epicentre of manufacturing companies in the 19th century.

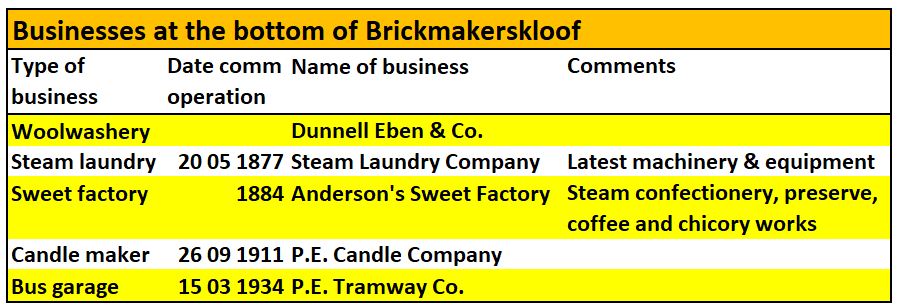

A chronological chart of one site being the ground at the bottom of Brickmakerskloof is indicative of the variety of industries being set up in the Valley.

Steam mills

In short order, two steam mills were installed in close proximity to the river. In Sptember 1848 the first to arrive was the mill for William Henry Coleman, the first of their kind in the Eastern Province. It was located on the lower corner of Military Road and Baakens Street. Two years later on the 26th April 1850, a steam mill owned by John Owen Smith, which commenced operations on 26th April 1851, soon followed.

The following operations esatablished in the Valley, opened in April of the following year, was probably more benign. In this case, The Algoa Bay Mooring and Watering Company piped water from a spring on the southern side of the Baakens River to a water boat at anchor beyond the surf.

Contemporaneously with these developments plans were afoot to to enlarge the lagoon to provide anchorage for ships. These plans were soon dropped when upon investigation a large rock bar prevented vesels sailing between the lagoon and the sea. With the later invention of dredgers, this would have been possible, but by then, the horse had bolted and rumble had converted the placid lagoon into a minute canalised river.

If the Baakens River had been an opera, the emotional tenor in July 1864 would have been bittersweet – bitter due to the Municipality granting permission to narrow the channel of the river while sweet would represent progress. The rubble used to fill in the lagoon was obtained from the rock excavated from the building of large buildings in Main Street which stretched all the way from Main Street to Chapel Street. Initially the plots created on the reclaimed land were to be sold and the proceeds used to create gardens. This did not materialise, so ultimately the money was used to purchase land further up in what is now known as Victoria Park.

Apart from the Handfield’s woolwashery in the area and the Dunnell & Eben’s woolwashery at the foot of Brickmakerskloof, woolwasheries were established on the valley floor in Rufane Vale and at Baakens Street. Amongst the other polluting businesses established in the valley was a steam laundry business. In an era during which the household was largely was largely srlf-sufficient, Port Elizaabeth had an incongruity viz clothes washing. This arose the paucity of water for household purposes as there was no water supply. In light of this water shortage, local laundry women would offer their services to wash the laundry in the numerous kloofs from Brickmakers to Cooper’s Kloof [now Albany Road]. The gradual filling in of the kloofs to lay roads, removed what had been the washing places for the local laundry women.

The opening of the Steam Laundry Company on the 20th May 1877 resolved this issue. The Company was formed on 10 September 1877. This enterprised utilised the premises of Dunell, Ebden and Co’s woolwashing establishment at the bottom of Brickmakerskloof. This site was fitted with the latest machinery and equipment and where wool had been spread there were now clothes drying. The closure of the woolwasheries in Port Elizabeth was occasioned by their transfer to Uitenhage where the “sweet” waters of the Zwartkops River was more conducive to woo washing.

Amongst the many commercial and industrial buildings which were constructed in the Valley was The Tramways Building. Built in 1897, it is located in the middle of the flood plain and has survived all of the floods and still remains there today.

Flooding

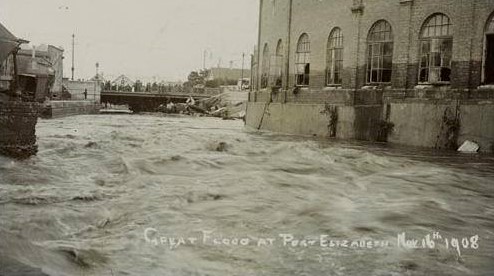

Colloquially what was known as The Great Flood struck on the 16th November 1908. Following a cloudburst in the Hunter’s Retreat area, the Baakens River came down in flood, causing tremendous damage in the valley and around the mouth. As usually happened, with such a small catchment area, the water level subsided again with great rapidity. Unlike the previous flood in the river which had resulted in minimal damage, in this instance, in this case it had caused substantial damage.

The reasons for this were twofold viz the use of the floodplain for various activities, mainly industrial, which resulted in the construction of various buildings and factories within the confines of the valley. The floodplain was now a hive of commercial activity. More ominously, after the Municipality had consented to the filling in the lagoon and the use of the reclaimed land for building purposes, the waters of the river which effectively channelised into a narrow canal which was only sufficient to handle the normal water flow. As a consequence, some of those affected by the flood damage, brought an action against the Council and the Commissioner of Public Works in September 1909.

Another contributing factor to the seriousness of the flooding was the fact that flotsam carried down by the torrent would become entrapped in piling of the bridge thereby creating a dam.

Having once glibly agreed to narrow the flow of the Baakens River, due to persistent unease by the residents of the town, soon to be declared a city, the Council reversed its original decision. Under all disaster epithets – torrential, severe, inundatory – the Council had little option but to accept a scheme to widen and improve the channel of the Baakens River. On the 9th January 1913, this scheme which included the building of a new bridge to provide a proper outlet in case of future flooding, was approved.

Bridges through the ages

The signature feature of Port Elizabeth’s weather is that it is periodically prone to devastating flooding. Partially culpable was a set of unique weather patterns which occur every second decade. This culminates in rain clouds stacking up over the town as if tethered to the ground, releasing all of their moisture within a few hours. As if this was insufficient to place the existing water courses under strain, mankind had played a pivotal role in aiding and abetting this calamity by an error of judgement. By filling in the lagoon at the Baaken’s lower reaches, and canalising the water flow, this tragedy had unwittingly been amplified.

Exacerbating the situation was the construction of bridges across the river. Under normal circumstances, due to the dearth of traffic and the placidity of the water, the use of the various drifts was satisfactory. As the volume of traffic increased, an alternative was required. In this case, bridges were the only solution. In her Social Chronicle, Margaret Harradine records that on the 7th November 1851, “heavy rain washed away ……both bridges over the Baakens.” The exact dates on which these bridges were built, cannot be ascertained.

The mid-1852, a new bridge was built over the Baakens River to replace one destroyed in November 1851. It was built according to a design by H.F. White and appropriately christened the Union Bridge as it united the northern with the southern parts of the town. In conjunction with this opening, the access roads were renamed as well, becoming the North Union and South Union Streets.

Elation at the completion of this bridge was profoundly misplaced as flooding over the 31st October and the 1st November 1857 swept away the five-year old bridge. The residents greeted its destruction with great shock and utter dismay.

This bleak pattern of flooding & destruction was set to repeat itself. After a hiatus of 10 years, over the 19th & 20th November 1867, Port Elizabeth once more experienced torrential downpours. Buildings were undermined and some collapsed. Similarities and parallels abounded with the September 1968 floods. Great damage was wreaked especially in South End which experienced the worst of the storm. The east / west roads were completely washed away in the deluge as these streets reverted to their former state as kloofs and waterways. Also damaged in this flood, was the Baakens bridge.

After many dashed hopes at an indestructible bridge being built over the Baakens River which could withstand the most severe torrential downpour, finally in 1892 the Municipality and the Harbour Board, which both had a vested interest in the project, agreed to fund a new bridge in the ratio of one third by the Municipality to two thirds by the Harbour Board. On the 25th August 1892, the foundation stone was laid by the mayor, R.H. Hammersley-Heenan.

After the devastating floods of November 1906, the Council finally approved to a scheme whereby the river canal would be widened and a new bridge would be built over the Baakens to provide a proper outlet in case of future flooding.

It would take almost another decade – June 1922 – before it came to fruition. Whereas the Council had originally planned to build a steel bridge – the existing one being cast iron – but the war made that impossible for the designers. The Trussed Concrete Steel Company of London were unable to procure steel. Instead reinforced concrete was substituted as agreed in 1916. A further delay was created by the war and its construction was postponed until the cessation of hostilities. Finally with the armistice in November 1918, the procurement process could once again proceed. On the 31st March 1920, the tender submitted by Murray and Stewart was accepted at a contract price of £20,564

Partial redemption

With the lower reaches of the Baakens River now beyond redemption with the tram sheds and various other buildings proliferating on the valley floor, its fate was sealed, never to revert to its pristine state.

Perhaps the Council’s conscience had been pricked as in September 1932 they agreed to set aside the Baakens River valley between Essexvale and Barnes’ Quarry as a Nature Reserve. Likewise, the Walmer Municipality agreed to add portions of land. Various measures taken to upgrade it such as the removal of the exotic prickly pears and the fencing of the reserve were undertaken. This was the commencement of Settler’s Park, the name given to this salvaged portion of the valley on 28th February 1952.

By 1900 the destruction of the lower reaches of the Baakens Valley was complete. Fortunately the upper reaches had been spared more by luck than design. Another bogeyman would arise in the 1960s when due to traffic pressure on the Cape Road corridor to the western suburbs, another dragon was released: The Baakens Valley Parkway project in which the valley would be permanently disfigured and defiled by an Expressway in the centre of the valley.

Resurrected on numerous occasions, this ogre would finally be slayed in the 1980s never to rise again.

What could have been

With the benefit of hindsight, would it not have been preferable to persevere the Baakens River as a park close to the centre of town. A grave wrong was committed in not retaining the original lagoon as a pleasure resort and boating facility. The death throes of this pristine wilderness were long and painful yet no civic figure, citizen or the Council sought to protect it.

Development of industrial concerns proceeded apace on the valley floor over the first half century, dooming this area to destruction. One could argue that a similar travesty was visited upon the lower reaches of the Papenkuils River. Whilst that may be true, unlike the Papenkuils River, the area adjacent to the Baakens River was never suited to industrial development. Instead it should have been reserved for residential and recreational use only.

Imagine seabirds skimming the water, seagulls screaching overhead and flamingos gracing its shores parading around on their long legs, as if on stilts, sieving minute creatures with their curved reddish hued beaks.

Instead of swearing undying fealty to progress and development, consider the environment too.

Don’t destroy the gems of nature.

Treasure them.

Preseve them.

One can only sigh “What could have been!”

Sources:

http://www.baakensvalleyaction.co.za/historical-interest

http://thecasualobserver.co.za/port-elizabeth-yore-happened-baakens-lagoon/

Port Elizabeth: A Social Chronicle to the end of 1945 by Margaret Harradine (2004, Historical Society of Port Elizabeth, Port Elizabeth)

The Saga of the Baakens Valley Article from an unknown newspaper probably the Eastern Province Herald by Ralph Jarvis & Keith Ross

I was interested to see the reference to R H Hammersley Heenan since I have been researching the Hammersley Heenan family for the last few months. I’m curious however about the date you give of August 1852 when you say the foundation stone was laid by the mayor, R.H. Hammersley-Heenan. According to all the records I have of RH he was born in that year. I dont think it can be a different person because the name Hammersley Heenan was not in use until about the 1870s. RH was actually born simply as Heenan but he and his brother adopted Hammersley in respect for their mother;s maiden name. Would it be possible for you to let me know where this piece of info came from? I don’t mean to sound critical at all – you have done a fantastic amount of work but I’m a little confused and want to get my info correct.

Hi Karen,

Thanks for pointing out the potential error. I will follow up & revert to you

Regards

Dean McCleland

Hi Karen,

The date should read 25th August 1892

Regards

Dean McCleland