If you were able to put the genie back in the bottle, what changes to the historic Port Elizabeth should not have been made or what should have been done differently.

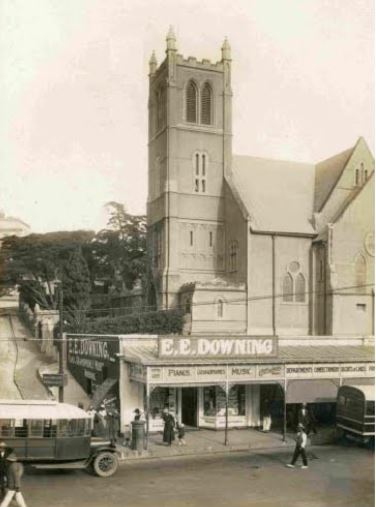

Main picture: St Mary’s Church’s frontage in Main Street with the elegant building behind hidden from view by the UBS Building

With progress comes destruction as an inevitable concomitant. It is ineluctable. One cannot halt change. If all change is not permitted, Main Street would still be lined by two storey buildings and the magnificent edifices of the City Hall and the Main Library would never have left the architect’s drawing board. These two buildings occupy a rare spot in the collective imagination — a mix of wonder, reverence and awe.

What this requires is the preservation of the classical era of a town; not the whole town in toto, but rather a segment in its entirety. Hence without attempting to freeze development of the whole, a segment representing that high point in the town’s development should have been selected.

St. Mary’s Church

History is replete with examples of ill-advised decisions with their unintended consequences. In Port Elizabeth’s case, the most egregious example occurred early in the town’s development even before the effects of the decision could be contemplated.

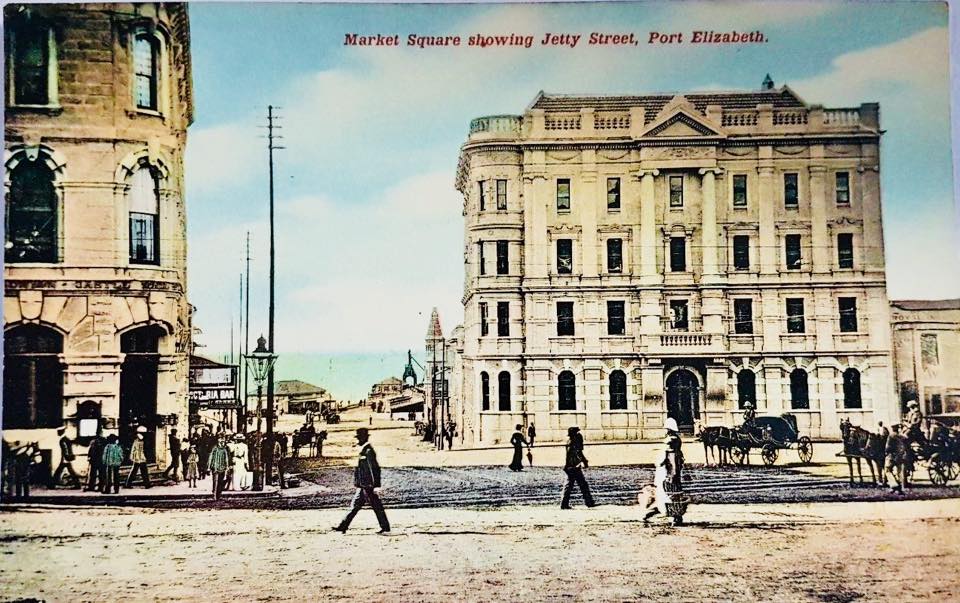

Market Square showing from left to right: Cleghorn’s Building, Main Library and St Mary’s Church without the stark UBS Building obscuring the view of St. Mary’s Church. If no changes had been effected over the years, it would have been possible to view this identical scene a century later. Unfortunately the Cleghorn’s building was destroyed by fire in 1896. After being rebuilt in 1904, it was finally demolished in 1972 in order to widen White’s Road.

The stunning facade of the St. Mary’s Church is no longer visible due to the UBS Building

The original grounds of St. Mary’s Church encompassed frontage onto Main Street. In order to fund the building of the Church, the church was compelled to sell some of its assets. As its most valuable asset was its land, that is what it decided to relinquish. A Deed of Sale reveals that the church wardens sold three plots of church ground which included the whole of St. Mary’s Terrace. It was sold for the princely sum of £33 to a Mr William Matthew Harries, a church warden, on the 12th November 1833. Apart from the fact that the church was compelled to repurchase portion of this land some thirty years later, the sale of frontage in Main Street would result in the aesthetic destruction of the area.

This error of judgement would permit the construction of the box-shaped UBS building lacking any architectural merit. Image what the area opposite the Main Library would have been like if the full beauty of St. Mary’s Church had been visible from Main Street. Ironically it is the rebuilt St. Mary’s after its catastrophic fire in 1895 which one can thank for the elegant current façade. The original structure was an unattractive oblong building with no aesthetic merit.

This bleak pattern would be perpetuated in the construction of the SARS building in St. Mary’s Terrace. Whereas the UBS Building can claim to possess a modicum of beauty, the SARS building can make no such claim. In fact, in my opinion, it is only fit for the wrecking ball.

Jetty & Strand Streets

Similarities and parallels abound all over the heart of the old town, but none more so that these two streets.

The one artefact that was amongst the top five most elegant buildings in the Port Elizabeth at the turn of the century was the Custom’s House. Unlike the other fine buildings which fell to the demolition crews, it was destroyed by an even less emotional foe, fire. In 1978 this magnificent building was badly damaged in a conflagration. Attempts to save the building failed culminating in its eventual demolition in 1982. No longer the entrée to the city, its architectural significance was no longer appreciated.

Customs House with its tower which was removed later on before 1925

Another venerable example, maybe not in the same league as the Custom’s House, was the Palmerston Hotel. Commencing life as a house, it was steadily enlarged over the years. During the 1930s when Henry Meyer and W.L. Levey were the proprietors, the existing building was demolished and the present eight storey hotel was opened towards the end of 1936. Like all more recent buildings in the world, this replacement had no endearing qualities.

Google Streetview of where the Customs House used to be located – October 2014

The construction of the Settler’s Freeway adjacent to and through the Strand Street area was to forever change the original heart of Port Elizabeth. Without question, the location of the centre of the town squashed between the shore and the hillock a few hundred metres inland, restricted access to this area. The introduction of the automobile exacerbated the situation. With the lack of parking, it was inevitable that future development would be outside this area. Without the construction of this freeway access between the northern and southern suburbs would always have been problematical. What it did however, was to destroy part of the heart of the city. Most would not mourn its passing but a significant part of old Port Elizabeth would forever be marginalised.

Palmerston Hotel 1900s before it was demolished and replaced by the Campanile Hotel

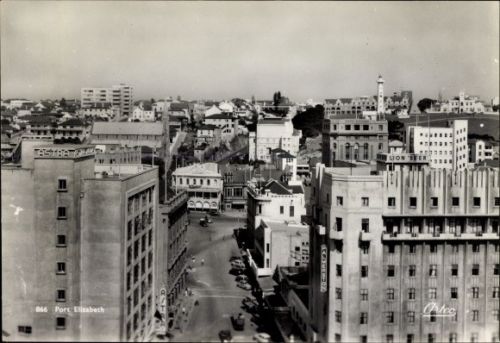

Main Street

Originally Main Street comprised a series of double storey buildings with a shop on the ground floor and accommodation for the proprietors above it. During the initial growth spurt of the town, they were replaced with taller buildings such as those of Fischer’s, Cuthbert’s and Birch’s. In accordance with the architectural designs prevailing during that period, they all possessed some architectural merits, many representing Art Deco designs.

Nonetheless, amongst the most impressive was the Mutual Arcade. This building was designed in Edwardian style by William Henry Stucke to fit the shape of the ground. It was opened on 24th December 1900.

The Old Mutual Arcade circa 1904 showing shops at ground level in Main Street

This was not to last. The nineteen fifties and sixties witnessed the destruction of the majority of these original buildings, all to be replaced with insipid concrete blocks.

This bleak pattern of destruction finally ran its course by the mid-seventies. The pattern of development was inevitable. Port Elizabeth was no exception to the rule. Unless the city’s growth had stalled during the 1950s, the replacement of the two or three storey buildings with more modern buildings would have been the order of the day.

Should this building have been demolished to make way for this building not in keeping in scale and style with its predecessor?

Jetty Street in 19th century

Jetty Street today

Integrity of renovations and refurbishments

A notable feature which abounded on most buildings of the pre-modern era in Port Elizabeth were the full-length canopies along the sea-facing walls. All of them were painted with stripes. Apart from this feature, balustrades and other railings were not merely humble poles but possessed some character.

Grand Hotel in the early 1900’s with their full-length canopies over the windows

In comparing the original buildings such as Donkin Row with its renovated modern version, a more detailed inspection will reveal that many such features no longer exist. Take the example of the canopy, which was pervasive in old photographs appears, to be non-existent today. If it still exists, it is unlikely to be faithful to its original design. In other cases, changes are required with the original design. For example, I will never take issue with the decision to relocate the outside toilet to the inside in the case of the dwellings in Donkin Street but the decision to amend the design of railings, windows et al is sacrilege. This should never have been permitted.

How not to renovate a building

An egregious example is the Post Office building

http://www.theheritageportal.co.za/thread/old-post-office-complex-port-elizabeth

Another example is the old Cuthbert’s Building:

This seven storey building was once one of the landmarks of the city, partly because it was one of the tallest in the city when constructed and partly due to the eye catching globe that adorned the top of the corner turret. Sadly the tower and the globe were lost, together with the ground floor canopy and first floor balcony. The body of the building has been concealed by a rain screen cladding, since the 1950s; firstly in aluminium but this was replaced in later years by blue glass. It is unclear what remains of the original facade behind. The result is that the building is unrecognisable and many assume it was demolished. The side elevation is still,however,visible and some elements of the original can still be made out

Cuthbert’s Building pre 1914

Cuthbert’s Building today

Left: Renovations to the Cuthbert’s Building have comprehensively destroyed its facade

Environment, flora and fauna

It goes without saying that the establishment of a town has huge ramifications on the environment and its flora and fauna. It is definitely no consolation that fragments of its most outstanding features have survived. The odds are that no more than a tiny fraction of the current inhabitants of Port Elizabeth are even aware of what the environment, flora and fauna was like 250 years ago.

Of all these features, the most prominent has to be the sand dunes. These stretched from Sardinia Bay across Walmer to Humewood. Like all ecosystems, they were in balance and played a pivotal or central role in providing the sand which maintained the beaches along the Humewood and Summerstrand coast. In an egregious error of judgement, it was assumed that after millennia of stability, that these dunes would ultimately engulf the harbour. What would impair this stasis was not nature by mankind itself. This nature recycling of sand with Algoa Bay has been further exacerbated by the construction of the breakwater.

Needless to say, but the ultimate solution will be to reverse portion of this action. This will entail once again permitting the area to the south and east of the NMMU to be reclaimed by the dunes. As a longer-term solution, it will probably require the pumping of sand from Sardinia Bay across its former path to the town’s premier beaches.

Aerial photo from 1930 showing Noordhoek dunes going right across Cape Recife. Originally the whole visible area was covered with sand dunes.

Amongst the initial victims of man’s influence, was the fauna. Tales of the early explorers of the 1700s, spoke of endless herds of elephants and buffaloes populating the area now known as Kragga Kamma. By the 1800s, the guns of the adventurers and farmers had felled the bulk of these populations. As a consolation prize, these animals were awarded a sliver of land in the Alexandria area as their home in the twentieth century.

Beneath a veneer of civilisation, lies the destruction of the natural environment. So was it in Port Elizabeth.

Clarion call to arms

Similarities and parallels abound with countless towns and cities around the world. The tensions between developers and historians will forever prevail. Especially in a third world country like South Africa, resources will always preclude the saving of all artefacts. If one adopts that attitude, historians will always face a series of false dawns and dashed hopes. Instead of savings all worthy buildings, precincts should be saved. These will permit one a peek into a previous age. This might even entail the demolition of totally inappropriate structures or alternatively modifying them substantially so as to more comply with the architectural style of the area. One such area in Port Elizabeth is Market Square with all its adjacent buildings. Another could be a section of Bird Street.

Jetty Street with the UBS and SARS building in the distance

It behoves us all to preserve our heritage. Not to do so, would doom our past to destruction either through its wilful destruction by developers or wanton destruction by squatters and drifters. Already it pains me that much has been lost. All that we have to remind us of such edifices are photographs. It is that loss that drives me to record the stories of not only the buildings, but also as far as is possible, the stories of its inhabitants.

With the benefit of hindsight, much more could have been done to save Port Elizabeth’s heritage especially in precints such as Market Square, portions of the hill and even Park Drive.