Little did the members of the Prince Alfred’s Guard realise but the Bechuanaland Campaign was to be last of the little colonial wars in which the Guard were destined to take part. After the Transkei and Basutoland campaigns, this would be the third “outing” during which the unit would be tested. In total, the unit would be away on duty for six months.

Main picture: Parade for the unveiling of the memorials in St. Mary’s Church on 20th September 1896.

Casus belli

In hindsight, it is now very apparent that many of the colonial wars arose due to misunderstandings and cultural differences between coloniser and colonisee. In this case it was an outbreak of rinderpest in the Taungs district north of Kimberley in 1896 which had most unfortunate consequences for the Cape Colony.

In an effort to stop the spread of the disease, the Government felt compelled to order the shooting of a number of affected cattle belonging to the tribesmen in the area, which was soon seething with discontent. Unable to understand the necessity for killing off their livestock, the owners regarded the regulations as a deliberate attempt by the Government to deprive them of their wealth. They were in a rebellious mood and when the authorities terminated this practice and paid compensation to tribesmen under Chief Molala, the action was interpreted as a sign of weakness by the Batlapin, Barolong and Batlaros clans.

Though rinderpest remained rife in his area, ex-convict Chief Galishiwe got the strange idea that the Government was, in fact, afraid to shoot any more of his cattle. Having not been paid compensation like Molala, he was also openly defiant, and matters were brought to a head when on November 28 1896, 17 infected cattle strayed on to the farm Trinidad and the police at Border Siding shot them on instructions from the Veterinary Surgeon for the district. The tribal leaders at Pokwani – not to be confused with the Pokwane in Basutoland – were incensed at the resumption of cattle-shooting and on December 2 one of them took an armed body of men to Border Siding, a small halt north of Warrenton, and demanded compensation.

Fighting breaks out

Rumours of armed demonstrations led the Assistant Magistrate of Taungs, Mr C. R. Chalmers, to go to Pokwani to investigate, and soon Galishiwe and a certain Rasabake were reported to be forming “Bodyguards”, ostensibly for their protection against the cattle-shooting police. A fortnight later, on 21 December 1896, about 100 armed blacks threatened Schaapfontein police camp near Pokwani, and when Sub-Inspector Elliott of the Vryburg police post went there two days later, he was stopped by Rasabake and an armed band of his followers between the police camp and the local store. Field-Cornet Blum, who had also been warned of possible trouble, was interfered with by the locals, and soon fighting had broken out, with Galishiwe, Rasabake and Phetlwe as ringleaders of the malcontents. On Christmas Eve, a European trader and his assistant at Pokwani were murdered, and Cape Police and 50 men of the Griqualand West Brigade had to be sent to Pokwani, where they were fired on and lost two killed before 260 reinforcements arrived and cleared the village, unfortunately without apprehending the ringleaders. With more than 6,000 men available in the Cape Mounted Rifles and Volunteer units in the Colony, there hardly seemed to be cause for undue alarm.

Press reports on the House of Commons motion for the reappointment of the Jameson Raid Inquiry Committee early in February 1897, and talk of holding some suitable commemoration on the 77th anniversary of the landing of the 1820 Settlers were among many subjects which thrust the Bechuanaland incident into the background, but the failure of the authorities to apprehend the culprits responsible for the unrest was brought painfully to the notice of the public when Captain H. V. Woon, with a patrol of 80 Cape Mounted Riflemen and 20 Basutos, tracked Galishiwe to the Langeberg, well to the south-west of Kuruman and 120 miles or more as the crow flies from Pokwani. There the rebellious petty chief had joined forces with Chief Toto and other rebels from Mashowing and Pokwani, totalling 700-800 men.

Toto refused to hand over Galishiwe and when the Cape Mounted Rifles attacked them, they repulsed the patrol and forced them to withdraw rather ignominiously to Kuruman, 50 miles off, with the loss of an officer and a private of the Cape Mounted Rifles killed, two wounded and 16 horses captured by the rebels. The reverse jolted the Government and on 18th February 1897, it was decided to raise volunteers if necessary, to deal with the serious trouble which now threatened. Commanding Officers of volunteer corps were informed by the Colonial Defence Secretary, Colonel Homan-ffolliott, that they should call for volunteers to hold themselves in readiness for active service, whilst reports from Bechuanaland came in to say that Chief Luka Jantjes was already boasting that the white men had fled like dogs before him.

Galishiwe’s men were looting cattle in the Kuruman district, and when called on to give himself up, his reply, so the Prime Minister, Sir Gordon Sprigg, revealed, had been, “No, I will not surrender. I know that I must die, and I intend to die here, fighting against the Government.” The Dukes, Cape Town Highlanders, Cape Field Artillery and Medical Corps in Cape Town, Prince Alfred’s Guard in Port Elizabeth and First City Volunteers in Grahamstown were all being asked for volunteers, and a number of burghers were also being called out. Some would guard the lines of communication, but a force of 600, mainly mounted men under Colonel E. H. Dalgety of the Cape Mounted Rifles, was expected to go into the Langeberg.

Prince Alfred’s Guard mustered

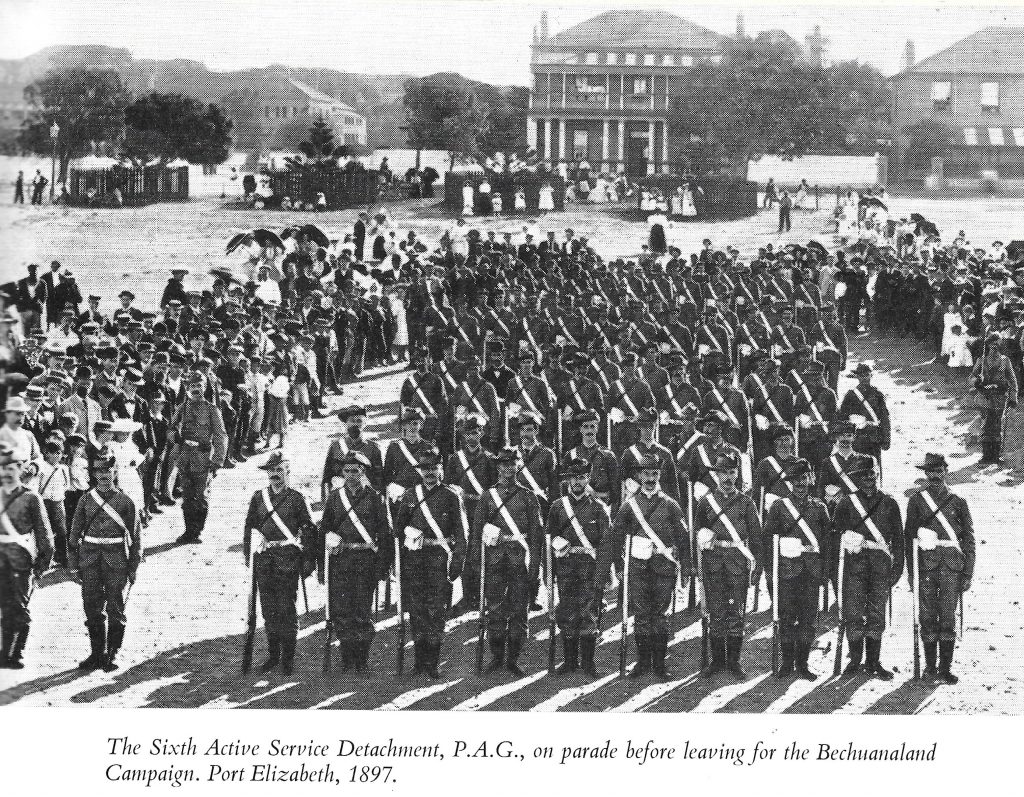

On 22nd February, orders were received at Port Elizabeth informing Prince Alfred’s Guard that three officers and 77 men would be required for Bechuanaland. There was great activity at the Drill Hall and only one out of the first batch of 78 volunteers at a hastily called parade next day was declared medically unfit. Very efficient arrangements had been made by the Defence Department for the issue of equipment and ammunition, and khaki uniforms were provided at once. A full parade was called for that same night, a farewell concert organised for the following evening and instructions published for departure of the Sixth Active Service Detachment by train at 2 p.m. on 25th February.

Port Elizabeth’s joy over heavy rains, which broke a drought that had endangered the water supply, was tinged with some nervous excitement at the prospect of once again providing men for active service, and on the day before departure of the detachment great indignation was aroused among Prince Alfred’s Guard officers when the railways communicated direct with all their employees who had volunteered and ordered them to remain at their jobs owing to pressure of work in the goods sheds. Colonel Gordon, in turn, ordered the men to ignore the railways circular and parade at 1.15 p.m. that day or face military arrest. The railways then countered with the threat that any of their men going on active service would be arrested for desertion of the Government Service.

The five enthusiastic and unfortunate railwaymen who had enrolled were ordered back to work at 1 p.m. and threatened with military arrest immediately afterwards, but owing to the shortness of time available to sort the matter out, they were not present when the detachment paraded at the Drill Hall next day under Captain J. R. MacAndrew, with Lieutenants Gilbert Murrell and F. W. Leeds as his subalterns, and A.J. Annison as Sergeant-Major. After the usual farewell addresses by Colonel Gordon, the Mayor (Mr. James Wynne), Sir C.F. Blaine and the Rev. Dr A. T. Wirgman, the detachment, headed by the Prince Alfred’s Guard band, marched to the station along streets lined with cheering crowds. There they boarded a special train, which pulled out for Kimberley at 2 p.m. to the strains of “Auld Lang Syne” from the band.

Long march from Kimberley to Kuruman

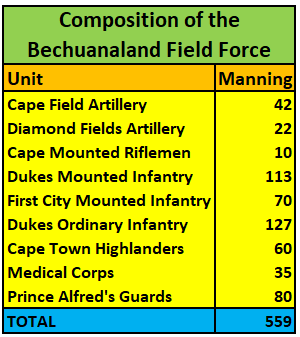

The volunteer contingents converged on Kimberley where the pipers of the Kimberley Scots played detachments to their camp. From this point, there was no railway line to Kuruman leaving the only option from antiquity, marching. There on Sunday, 2nd March, the band of the Griqualand West Brigade played and drew a large crowd. Camp was struck that evening and the main column began its march to Kuruman, expecting and hoping to be attacked on the way. Health in the camp was excellent and the column, known as the Bechuanaland Field Force, comprised the following units.

Probably because PAG were not mounted, they were split up for garrison duties at Vryburg under Lieutenant Murrell and at Taungs under Captain MacAndrew. Completing the Force were 31 despatch riders of the Intelligence Department under an officer, seven staff officers, seven clerks and 33 muleteers and “boys”. Some 200 burghers from Vryburg and elsewhere were already at Geluk, but were expected to leave hurriedly in response to urgent messages from Kuruman stating that the tribesmen were massing for possible attack on the historic little town made famous by Moffat and Livingstone.

Initially it was envisaged that the mounted men would be used for the actual clearing of the Langeberg, leaving the infantry the not very inviting prospect of watching the lines of communication. The Signals Corps laid a temporary telegraph line from Border Siding to Kuruman to supplement their heliographs, which could operate over about 30 miles but were completely dependent on the weather, as their mirrors were ineffective unless the sun was shining.

Reaching Barkly West at breakfast time on the 4th March, the main column resumed their march in very hot weather the same day, with a long trek ahead of them to Kuruman. There the Vryburg burghers were now concentrated, with the black warriors only some 15 miles off and holding all water points between there and the Langeberg, towards which 150 Upington burghers were reported to be advancing. Toto and Luka Jantjes were protesting their loyalty but had nevertheless taken possession of the water at Kathu, south-west of Kuruman and on the road to Olifantshoek and the Langeberg, where· they were gathering the fighting men of the Batlaros.

No contact had yet been made with the enemy, but by March 10 the column was already running into trouble because of horse sickness, scarcity of water and transport problems.

Unromantically stuck at Vryburg and Taungs, the Prince Alfred’s Guard detachment could have been little but bored and hot. But they were not forgotten, and in Port Elizabeth itself entertainments were arranged to raise money to supply the men with “such luxuries as tobacco, newspapers, etc.” whilst their regimental comrades at home discussed the great prospect of having electric trams running in the city by the time the detachment returned. On 16th June 1897, the first of the new electric trams replaced the old horse trams and by 20th July they were running to The Hill, stirring up much dust on the unsurfaced roads.

Reaching Kuruman after an 11 days’ march, the main Bechuanaland column rested there. Just before their arrival smoke could be seen and firing heard from Gamapedi [now GA-Mopedi], down the Kuruman River, which loses itself in the sand after rising in the “Eye of Kuruman“, a remarkable spring in a dolomite cave from which some 5,000,000 gallons of water a day regularly flows. Camped a few hundred yards north of the famous Moffat Mission Station, the column received news of an engagement between the Vryburg Volunteers and a rebel band early that morning, in which the rebel chief, Mongoli, his brother and 30 others were reported killed, for the loss of two of the burghers killed and two wounded. One of the dead was V. Fletcher, a young volunteer who originally came from Maclear, in the Eastern Province.

With three of its wagons broken down, a number of horses already lost and with rinderpest sweeping off its slaughter cattle, the main column needed some days’ respite before setting off for the Langeberg. SergeantMajor Owen of the Medical Corps had died of fever on the way, Private Broughton of First City had had to be left at Grootfontein with a small party to give him a chance to recover and Lance-Corporal Jeffrey of the Cape Town Highlanders was in hospital with fever. The transport mules had found the going very heavy through the sand, snakes were plentiful, many men were suffering from bad sunburn on their bare arms, and there was already a fair amount of grumbling about the lack of baking powder and the miserable quantity of salt in the rations.

False rumours reaching Kuruman about war between England and the South African Republic [Transvaal] did not help to raise the men’s spirits, and in a very short time people were criticising the authorities for making the volunteers concentrate at Kimberley instead of at Vryburg, which was nearer the probable scene of operations and also had more transport available. The column itself was further delayed at Kuruman through the non-arrival of supplies by wagon from Kimberley, and by March 22 they were bemoaning yet another delay through the breakdown of wagons sent from Vryburg.

It had now become wet and although official reports insisted that the health of the men was good, independent evidence was that there was much fever about. One of the Dukes mounted men died on the 18th from pneumonia.

It was not till nearly the end of March that the main column under Colonel Dalgety was at last able to leave Kuruman’s tented camp for Kathu on the road down towards Olifantshoek and the Langeberg. Captain Pennell and 85 all ranks, with one 7-pounder gun, were left to garrison Kuruman, to which Prince Alfred’s Guard were to move as soon as possible.

On the way from Vryburg, on March 24, the Prince Alfred’s Guard detach-ment under Lieutenant Murrell lost two of their number, Privates H. C. Kelsey and J. Searle by drowning and arrived at Kuruman on April 3 with a strength of only 22 other ranks. The two men’s bodies were later exhumed and sent to Port Elizabeth.

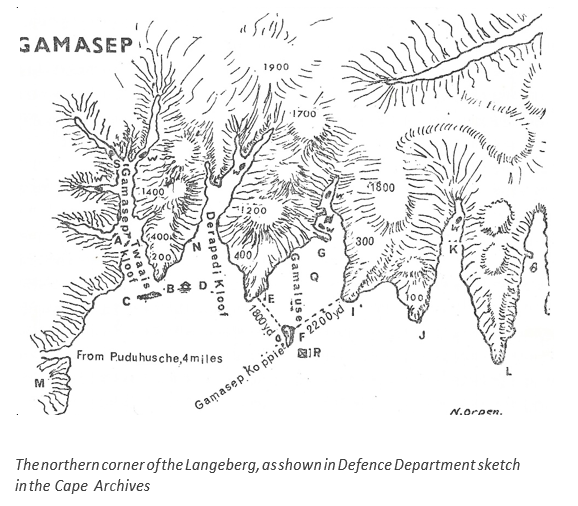

Colonel Dalgety was expecting to be able to put in an attack on the Langeberg within a few days and the little Prince Alfred’s Guard detachment was soon on its way to the front. The Dukes and Cape Town Highlanders had already been sent on from Kathu with two 12-pounders to occupy Ryan’s Store, in preparation for an attack on Gamasep Kloof, the nearest of the four deep kloofs which run into the Langeberg mountains for about two miles on its eastern side, sheltering the small streams which contain the only water in the whole area.

Colonel Dalgety’s plan was to divide his force into four columns. A North-West Column of burghers under Commandant Wessels, was to go round the Langeberg with the Vryburg volunteers to cut the rebels’ line of withdrawal; a Northern Column of E Squadron, Cape Mounted Rifles and the First City mounted men under Captain Woon would move up the mountain north of Derapedi Kloof and close in on Gamasep Kloof, whilst a Southern Column made up of Cape Mounted Rifles, Dukes Mounted, some Gordonia Volunteers and a Basuto Contingent under Captain Johnson of the Dukes was to seize the koppies south of Gamasep. Finally, the Main Column, under Dalgety himself, was to make a frontal attack on Gamasep with two Maxims, three 12-pounders of the Cape Field Artillery, a 7-pounder of the Diamond Fields Artillery, 114 Dukes, 58 Cape Town Highlanders and 50 Gordonia Volunteers who were to act as horse-holders. The Prince Alfred’s Guard detachment of 22 under Lieutenant Murrell luckily arrived at Ryan’s Farm in fine, warm weather in time to be included with the infantry in the Main Column. Between 6 and 7 p.m. on April 5 the columns moved out of Ryan’s, heading for the Langeberg about 16 miles away. Surgeon Lieut.-Colonel E. B. Hartley, V.C., and a party of stretcher-bearers with three ambulances accompanied the Main Column, which also included eight wagons, a Scotch cart and nine water carts.

The northern corner of the Langeberg, as shown in Defence Department sketch in the Cape Archives

KEY: A. Twaaiskloof or Gamasep. B. The Fighting Koppie. C. Ridge south-east of Fighting Koppie. D. Pearce’s store. E. Round koppie. F. Gamasep koppie of Gamadotoe. G. Galishwe’s koppie. I. Northern point of Gamaluse J. Southern point, Laboong. K. Laboong kloof L. Northern point of Laboong. M. Southern koppies of Polinyane. N. Derapedi. Q. Gamaluse. R. Site of main camp and new well. S. Luka’s laager of wagons about 4,300 yards from C.

At about 1.30 a.m. on 6th April the Main Column halted at a spot about three miles from Gamasep, where the Northern and Southern Columns had left their horses. There Dalgety waited till first light, when he ordered the advance. Four or five shots rang out from Gamasep as the column began its move, but at 6.30 they arrived unscathed at the entrance to Twaaiskloof, where Dalgety again halted, to look for the Northern and Southern Columns, who were supposed to have climbed the spurs to the north and south of the entrance to the kloof. He waited half an hour without seeing a sign of them and then decided to attack Luka Jantjes’ village, though the rebel himself had moved his laager deep into the kloof, about 4,300 yards from a ridge at its mouth.

A scouting party ahead of the column was fired on from schanzes on the right as they moved towards Gamasep Koppie. Captain “Tim” Lukin was ordered up with the Maxims to check the enemy fire and as soon as the rest of the column arrived a couple of 12-pounder shells were put into the village, with one going through Pearce’s store, which stood a mile or so north of the so-called “Fighting Koppie” at the entrance to the kloof The Dukes under Lieut.-Colonel Spence extended and rushed the village under heavy fire from the hills to right and left, shots from the right almost reaching the column’s wagons and horses some 1,500 yards away.

At this stage, a message arrived from Woon to say that his column was held up by a deep donga, to the right front and was unable to advance. Dalgety ordered them to fall back on the Main Column as the Dukes tried to push on with a Maxim on either flank. The rebels, however, were well hidden behind schanzes and the 7-pounder had to be brought into action to silence them, Sergeant Court of the Cape Mounted Rifles being slightly wounded and having his horse killed in the effort.

Meantime, rebel reinforcements were sighted coming from the direction of Gamaluse Kloof and their fire on the right was increasing. The Cape Town Highlanders and Prince Alfred’s Guard were sent in to hold a long ridge on Dalgety’s right and deny it to the enemy, and Captain Searle went forward with his men in extended order, taking the ridge and halting with his left flank in contact with the Dukes. Rebel fire continued heavily. Lieutenant M. Harris of the Dukes, who had originally joined Prince Alfred’s Guard in March 1892 and been commissioned before going to Cape Town, was badly hit in the thigh, and Lieut.-Colonel Hardey was slightly wounded whilst attending to him. Major T. J. J. Inglesby’s Cape Field Artillery 12-pounders caused the rebel fire to slacken, but then a body of mounted rebels was seen moving to the left rear to attack the wagons. Dalgety himself galloped off and found 80-100 of them dismounted and moving quickly under cover towards the rear of the column.

Men of the First City, from the Northern Column which had pulled back, and some of the Gordonia Volunteers were quickly extended along a ridge only some 30 yards from the wagon laager, and Inglesby traversed one gun right round and forced the rebels back with case shot.

Colonel Spence, with the left company of the Dukes plus Captain Woon’s Cape Mounted Rifles, was then ordered to attack a koppie on the end of a spur to his left, but Woon had not moved far before he turned back to the wagons, as he thought the threat there more serious. It was already 1 p.m., and there was still no sign of Johnson’s column, so Colonel Dalgety fell back slightly and formed a new laager about 800 yards to the right rear, on rising ground with another stony koppie about 600 yards to his right rear.

The infantry had no sooner begun to retire than heavier fire was opened on them, continuing until a laager was formed in the new position, from which Colonel Dalgety ordered the horses and draught oxen back to Ryan’s Farm for water with an escort of Gordonia Burghers. They were barely a mile and a half up the road to Ryan’s when about 50 rebels fell upon them, but the Burghers beat them off and then the Maxims opened up on them and killed several.

The sun was just going down when a light on the heights at the end of Twaaiskloof about four miles away signalled that Johnson was there, with his men suffering severely from fatigue and lack of water. He had lost touch with the man carrying his heliograph and had been unable to contact Dalgety any earlier.

The infantry at the laager spent a disturbed night and had to stand to from 3.15 a.m. on 7th April, whilst Johnson’s column moved some five miles along the top of the mountains in a south-easterly direction under cover of darkness. The column was now to the left of the laager, weak, footsore and thirsty, and with Luka’s men closing in on their rear and left front to cut them off.

By 10.30 a.m. Johnson was falling back on the Main Column – whilst the Dukes, 30 of the First City and a Maxim – moved out to cover his withdrawal. A short while later Lieutenant De Havilland and Private Barry of the Dukes Mounted from the Southern Column staggered into camp, De Havilland reporting that he had been cut off whilst trying to find water for the column. He had been hit twice but was only slightly wounded. On their return with the horses from Ryan’s at about 12.30, the burghers went out to help bring in Johnson’s exhausted men, and Colonel Spence’s force burnt Twaai’s kraal at the foot of the mountains, after meeting little opposition.

It was not till 2 p.m. that Johnson’s men came in, nearly all in bad shape. They had lost one Basuto, killed that morning. Sixty burghers, covered by the Highlanders and Prince Alfred’s Guard with one Maxim, were now sent off into Gamaluse Kloof to burn the village of the rebel Andries Gasibone and soon the 50-60 huts were in flames. Dalgety himself took another party to the entrance to Twaaiskloof and put about a dozen rounds from the 12-pounders into the rebel laager some 4,200 yards up the Kloof. Heavy fire was directed at the guns from a koppie on the right, but the party withdrew safely.

Lieutenant Harris, whose leg had had to be amputated, died that night and was buried next day before Colonel Dalgety moved the infantry, with some guns, to a strong position on the stony koppie to the right of the laager, leaving them there and then withdrawing the mounted men and transport to Ryan’s Farm. With him went the wounded, which included three High-landers, two of the Dukes, one member of the First City detachment and Sergeant Court of the Cape Mounted Rifles.

The operation had hardly been crowned with success, and Dalgety reported that he considered the Langeberg the strongest position he had ever seen. The only water other than at Ryan’s Farm was in the three or four deep, narrow kloofs running two to three miles into the 30-mile long mountains, and the entrances to these kloofs were commanded on either side by steep hills 800-1,200 feet high which could only be reached by crossing spurs strongly fortified by the rebels.

The unfortunate infantry was left to hold the position on short rations for two days until a convoy could get up with supplies. The laager was left under Lieut.-Colonel Spence and consisted of some 250 men of the artillery, Prince Alfred’s Guard, Cape Town Highlanders and Dukes infantry, who soon christened the little knoll, about 1,000 yards east of Gamaluse Kloof, Spence’s Koppie, after their regimental commander. The greatest problem, Colonel Dalgety reported to Cape Town, was the “Utter absence of water“. Owing to drought, the situation was worse than ever. In addition, rinderpest was killing off many of the transport oxen.

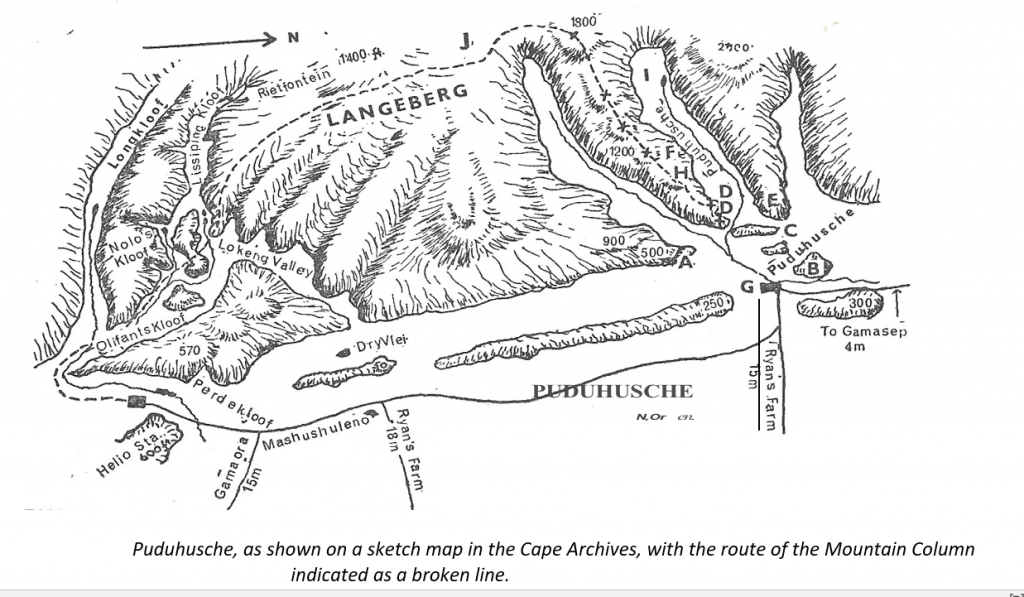

As more than 100 of their fellow Guardsmen marched behind the two hearses at the military funeral of Privates Kelsey and Searle at Port Elizabeth on April 14, the mounted men of the Bechuanaland Field Force were busy at Ryan’s preparing to move with two 12-pounders and a Maxim gun. At 7 that night, they rode out to join the infantry and the rest of the guns at Spence’s Koppie. Travelling through the darkness, they marched towards Toto’s stronghold of Puduhusche and before dawn they were only some three miles from the tribal village. At daybreak they moved forward to the attack.

Opposition was slight and they quickly took and set alight 250 huts, before moving on southward for nine miles to a spot some three miles east of Lokeng. Here they went into laager for the night and, at dawn on April 16, the column again moved out. This time they destroyed rebel kraals in Lokeng Valley right up to within five miles of Olifant’s Kloof, burning 400-500 huts, and capturing 200 cattle and 20 horses. Opposition was only slight, and the column suffered no casualties as the warriors at Lokeng fled on being shelled.

With the sky overcast, few heliograph messages got through for several days to keep the outside world posted with Colonel Dalgety’s progress, but by April 20 there was nervousness again at Kuruman, with reports coming in of natives massing 20 miles to the north-west at Gamapedi (not to be confused with Gamasep.) Thunderstorms and heavy rain in the Langeberg temporarily put an end to active operations and on the 21st April the Dukes, the Cape Mounted Rifles, artillery and Prince Alfred’s Guard left Spence’s Koppie to rejoin the main body at Ryan’s, leaving the Highlanders, 40 mounted men of First City and two guns to hold the koppie.

Within a few days the main column left Ryan’s to rejoin the little garrison of Gamasep at Spence’s Koppie and then move on to Olifantshoek, from which they reconnoitred some four miles up Olifant’s Kloof, with frequent small skirmishes with the rebels. Patrols from Gamasep, now strengthened by a detachment of 7-pounders of the Diamond Fields Artillery, were also active, and dispersed a band of some 60 rebels at a range of about 2,500 yards from the laager on April 25.

That same evening the Olifantshoek laager was attacked. Fighting lasted for only 10-15 minutes, with the rebels being driven off, but one of the camp’s drivers was killed and five were wounded.

From Olifantshoek an hour after midnight on the night April 27-28, a column of 200 men from the mounted Dukes, with some of the Vryburg and Gordonia burgher volunteers, left to occupy the hills at the junction of the Olifant’s and Riet Kloofs, some five miles from the camp. An hour later the main column, 370 strong and consisting of all corps in the laager except some Cape Mounted Riflemen who were left to guard the camp, set off up Olifant’s Kloof with two Maxims and one 12-pounder. They met with no opposition, and both columns halted and dismounted at the mouth of the Riet Kloof at sunrise, when the men sent up into the mountains signalled that the enemy were advancing over the hills from the back of Lokeng. They were easily driven back by the men from Gordonia and one company of mounted Dukes, who advanced into the hills to the north.

Of Galishwe, the main culprit, there was no sign, but it was believed that he and his men had withdrawn deep into the mountains at a time when there was a great deal of sickness among the troops, apparently as a result of eating meat tainted with rinderpest. Colonel Dalgety himself was on the sick list, and with the rebels firmly ensconced in mountains nearly 3,000 feet high and extending over 25 miles, a suspicion was arising that the campaign was likely to prove considerably longer than at first expected.

By the evening of 8th May, the day that 43 of the original trouble-makers from Pokwani were found guilty of sedition at Kimberley, hopes were nevertheless running high with the Bechuanaland Field Force’s main column, which included a detachment of Prince Alfred’s Guard. Fifty other Guardsmen were at Taungs, about to leave for the Langeberg, escorting a supply convoy as a safety precaution after three wagons loaded with rations had been captured by tribesmen between Ryan’s and Olifantshoek.

Moving in two columns from Olifantshoek on the evening of Saturday, May 8, Colonel Dalgety attacked the rebel stronghold of Puduhusche, where the highest point of the Langeberg rises to some 3,000 feet. Captain Johnson commanded the one column, consisting of 64 Gordonia Volunteers, 35 men of No. 13 Rifle Club, 91 mounted Dukes and 30 water carriers. They proceeded along the mountains via Olifant’s Kloof to attack Puduhusche in the rear, whilst the main column left camp two hours later.

Most of the main column, except Colonel Dalgety and his staff and the advance guard and rear-guard of Gordonia burghers, were dismounted. Sixty-three officers and men of E Squadron, Cape Mounted Rifles led the way, followed by two Maxims with their detachments, and then 24 officers and men of the Cape Field Artillery with their two 12-pounders, and 12 members of the Diamond Fields Artillery with one 7-pounder. The artillery was followed on the march by 50 Gordonia Volunteers, 25 of the Mount Temple Rifle Club, 25 of the Native Contingent, 17 Medical Corps and then the main body of the infantry, consisting of 75 Cape Town Highlanders and Prince Alfred’s Guard and 107 Dukes. Dalgety’s staff numbered 19.

The whole column, an eyewitness wrote, was enveloped in clouds of dust but continued on the move with short halts, taking the road towards Ryan’s Store and then turning off towards Toto’s stronghold of Puduhusche. No talking or smoking was allowed, and they kept going till 1 a.m. on Sunday morning, by which time they were only about four miles from their objective. The night was fresh but not uncomfortably cold and they slept for some hours where they had halted, before getting up to eat a hurried breakfast.

The attacking force had already begun to move off, when a heliograph signal from Johnson was flashed from the mountains, asking for a postponement to allow his column an hour’s rest. About 200 yards out, therefore, the attacking force halted in two lines, the firing line, extended to six paces, consisting of the Cape Mounted Rifles on the left under Captain Woon, Prince Alfred’s Guard under Lieutenant Murrell in the centre, and on the right the Cape Town Highlanders under Captain Searle. Behind them, in support, were two companies of the Dukes and the Native Contingent, the whole infantry force being commanded by Lieut.-Colonel Spence.

A: Strongly fortified point 400 feet high; the rebels allowed the firing line to pass A and B and to get within 600 yards of C before opening heavy fire on the left and right rear from A at 75 yards and from B at 500 yards.

B: Solitary koppie 100 feet high, from which the rebels fled as C was taken.

C: Looked like clay pits from H but was really three terraces of white rocks tilted on edge. A position of immense strength, on which artillery had little effect. Toto and his son, Sampie, directed operations here.

D: Strongly schanzed positions on which rebels evidently intended to fall back from A but occupied at 10.40 by the Gordonia Volunteers.

E: Koppie at end of north ridge rushed by Gordonia Volunteers from D when the Cape Town Highlanders charged C at about 1:45 p.m.

F: Point reached by Cape Town Highlanders and Gordonia Volunteers at 4.45 p.m. when burning wagons.

G: Bechuanaland Field Force laager at Pearce’s old store, from which the 12-pounders fired. H: Headquarters of the Mountain Column attacked at 12.20 p.m. from the south.

I: Lowest water in Puduhusche Kloof.

J: Point on mountain where Mountain Column attacked rebels at 4.5 a.m.

“C” was charged and secured by the Cape Town Highlanders and Prince Alfred’s Guard from ridge in rear, up which Gordonia Volunteers were advancing from D to E. “A” was carried by the Dukes and Basutos at 1.15 p.m., practically annihilating the rebels.

With the order to advance, the troops moved forward towards a large koppie to the left of the night’s camp site and when they reached a point about 500 yards from the rise, they came under heavy fire from five different localities. The infantry immediately dropped flat, and in a few moments Captain H. T. Lukin, who was years later to command the South Africans in France, galloped up with a Maxim and opened fire almost before the horses had been sent back. The infantrymen fired on the koppie to the right and to the front for about half an hour, but at one stage had to pull back a few paces to better cover.

Some of the Guards and Highlanders rallied round the Maxim, but several men were wounded and Captain Searle of the Highlanders, with Lieutenant Malley of the Dukes, displayed conspicuous bravery in going out under heavy fire to bring in Private Anthony Castleman of Prince Alfred’s Guard, who had been wounded in the leg and was unable to walk. Whilst Corporal Elder of the Cape Town Highlanders collected the wounded man’s rifle and picked up Malley’s signalling flag, the two officers carried Castleman back to safety under cover.

Though reported to be progressing well more than two weeks later, Castleman, who had joined the Guard in January 1896, died in hospital at Kuruman on 2 June 1897 and was buried with military honours the following day.

At the time Castleman was hit at Puduhusche on May 9, ammunition was already running short among the infantry and, on a signal, the Maxim carriage galloped up with fresh supplies, which were quickly issued to the men. A detachment of the Cape Mounted Rifles under Captain Woon had already advanced to within about 70 yards of the enemy, who were sheltering behind a schanz, when Major Inglesby opened fire with the Cape Field Artillery’s 12-pounders. According to contemporary accounts, they “did much execution”.

The Dukes and Cape Mounted Rifles then concentrated their fire on the koppie to the left, whilst the Cape Town Highlanders and Prince Alfred’s Guard advanced up the kloof, firing volleys by half companies in the approved, well-disciplined manner of the day. They advanced gradually until about 100 yards from the enemy, when the order was given, “Fix bayonets – charge!” With a wild cheer and led by their officers, the men rushed the schanzes and put the enemy to flight, the rebels being followed by some rapid fire to see them on their way. In traditional style, three lusty cheers were given on the objective, whilst Captain Johnson’s column took up the firing on the fleeing rebels from the rear and from their left flank, driving them over towards Gamasep. Colonel Dalgety was soon on the scene himself and some Gordonia Volunteers who followed him into the kloof joined the infantry in burning Toto’s laager. A small force under Searle nevertheless kept up the pursuit for some distance into the kloof until the approach of darkness and, a movement by some tribesmen to cut off the party’s retreat, induced him to fall back. The column then waited for Johnson’s mounted men to return after dark, before retiring into laager for the night and marching back to Ryan’s next day for water.

Casualties totalled three Cape Mounted Rifles killed and 13 men wounded, including Castleman and also Private Watkins of Prince Alfred’s Guard, the latter being only slightly injured.

A few days later, on May 14, the Prince Alfred’s Guard detachment under Captain MacAndrew arrived at Kuruman from their tedious spell of garrison duty at Taung, going forward next day to join the main column at Ryan’s Camp. There they found the force resting, but MacAndrew and 50 of the Guard were sent off with four days’ rations for Lokeng on the evening of May 25, by which time Toto was reported to be back again in his old Puduhusche position, with the Gamasep position also considerably strengthened. It was difficult to see just what Dalgety’s force was accomplishing, and criticism of the conduct of the campaign was beginning to mount as news was published throughout the Colony.

Horses and mules were dying at the rate of three or four a night from anthrax, to add to Dalgety’s troubles, but the main target for criticism remained the commissariat and all concerned with organising supplies for his force. Several of the wells newly dug by the troops were already showing signs of drying up, and on May 28 MacAndrew’ s men were moved to Deben to open up wells.

A week later, a strong rebel force attacked the camp at Gamasep but, in an action lasting three-quarters of an hour, the little garrison under Captain Hickson lost only one horse killed and drove the attackers off. At this stage, as one of the by-products of the rebellion, the telegraph construction party was busy within six miles of Kuruman, and it was hoped that a direct link with Cape Town, via Barkly West, would be established by June 7, by which time the rebellion was being looked upon as virtually over, though no one had yet got anywhere near laying hands on Galishwe.

In fact, criticisms, which were later to be publicly aired in the S.A. Volunteer Gazette, were being made for “all the delays in finishing off a little job that should have been long ago ended“. One correspondent signing himself “Volunteer” wrote scoffingly to the Cape Times with regard to the fight at Gamasep. He had, he said, been present, when “about twenty dirty niggers behind a few rocks (at that time the place was not schanzed) kept the whole of the main column, including three rifled cannon and two Maxim guns, at bay from 7 a.m. until 2 p.m., firing volleys into the rocks or against the face of the mountain, where the bullets were falling like hail.” He conceded that the infantry, standing in the open to be shot at, displayed great personal bravery, but, like many others, he implied that the whole campaign was badly misdirected. Others leapt to the defence of Colonel Dalgety and the officers but made scathing remarks about the burgher contingents.

Captain H. H. Parr in A Sketch of the Kqffir and Zulu Wars later suggested that the force was sufficient, if properly handled, to capture the Langeberg in one day, and it was therefore surprising that the authorities began paying off the burghers early in June and calling up further volunteers to finish the job.

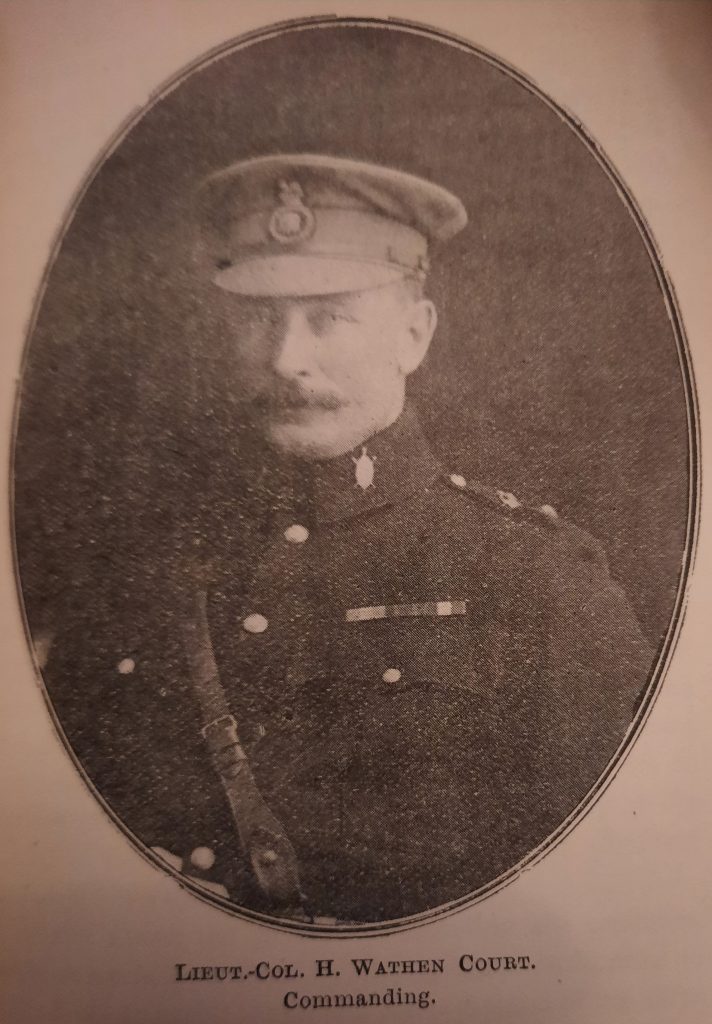

By June 10, Prince Alfred’s Guard had already selected another 94 men for medical examination. They were for the Seventh Active Service Detach-ment, which was already engrossed in preparations when Quartermaster–Sergeant Beadle and Private Watkins arrived back, invalided from the front, with fever and a light head wound respectively. Lieutenant A. Wares and Surgeon-Lieutenant H. B. Slater were to accompany the detachment, which was to total 106 men, under a captain, whose selection was causing considerable dissension among the officers. Colonel Gordon finally settled the argument by nominating Captain H. W. Court to command the detachment, which left by train on June 16 to join the flow of reinforcements, all agog with the news of the closure of the Johannesburg Stock Exchange on receipt of the startling news of Barney Barnato’s suicide by jumping overboard from the Scot whilst on his way to England.

In addition to the Port Elizabeth contingent, men from Cape Town, Graham-stown, King William’s Town, and elsewhere were on their way to strengthen the Bechuanaland Field Force. It was now winter and bitterly cold on the barren veld of Bechuanaland, and to add to the worries of the medical staff, smallpox broke out in the Kuruman camp, a mild case being diagnosed among the Kaffrarian Rifles. Frantic wires were sent off along the new telegraph line for supplies of vaccine. On July 1, Private George Madge of Prince Alfred’s Guard died from acute pneumonia at Kuruman, and reports continued to come in from the Force reporting illness, especially dysentery caused by drinking brack water and eating tainted meat.

Nevertheless, by the 5th July, detachments of Prince Alfred’s Guard, First City, the Kaffrarian Rifles and the Queenstown Rifles were encamped at Kathu, with the Kimberley Rifles on their way to Gamasep to relieve the older detachments of the Dukes and Prince Alfred’s Guard. The following day, and many months overdue it seems, 25 special water carts left Kuruman for the front, where the latest information was that Galishiwe was now in the Korannaberg, in the northern extension of the Langeberg.

Without tents, the Guardsmen were having a tough time, for it was bitterly cold at night and they slept fitfully beneath blankets often covered with frost. However, the camp at Kathu had been considerably improved and renamed Fort Sims after the officer responsible for opening up the springs on the site, where Captain Court was now in command.

Galishiwe gaily returned to the Langeberg and criticism was being openly voiced in Bechuanaland about the dilatory way in which the force of some 1,700 men was being employed whilst the rebels could come and go as they pleased, stealing horses and generally being a nuisance. To top everything in what appears to have been a most unsatisfactory state of affairs, two officers of the Geluk Burghers were arrested on a charge of murder on 14th July as a result of the alleged shooting of seven friendly blacks at point-blank range whilst on patrol during the previous month. Great excitement now reigned among the burghers in the district, and impatience at the continued delay in apprehending Galishiwe was growing.

Real efforts were being made to organise a proper water supply, but when 100 men of the Cape Police drove the rebels out of a kloof in the Koranna-berg, they once again had to fall back.

At last, on July 27, the main column struck camp at Ryan’s and moved out, with each man carrying only three blankets, a greatcoat, and a spare pair of boots in addition to his rifle and ammunition. Special pumps and tanks had been completed, and the water carts could now be filled at the rate of 200 gallons a minute. Arriving at Gamasep next afternoon, the force spent July 29 in detailed reconnaissance and in final preparation for an attack next morning. The main objective was Galishiwe’s position in Gamaluse Kloof, which Colonel Dalgety planned to outflank on both sides during the night. A “Blue” Column (Prince Alfred’s Guard, Kaffrarian Rifles, Queenstown Rifles and Kimberley Rifles) under Lieut.-Colonel Spence was to advance up on the left from Gamasep at 2.30 a.m. to turn the enemy’s right flank, whilst Captain H. B. Cumming of the Kaffrarian Rifles, with a “Red” Column of mounted men, outflanked the enemy on the opposite, northern, side. The Centre Column, commanded by Colonel Dalgety himself, consisted of the Dukes, Cape Town Highlanders, First City and Oudtshoorn Rifles supported by the field and Maxim guns, and was to launch a direct frontal attack. It was reckoned that there might be a full week’s fighting ahead.

At 2.30 a.m. on July 30 Colonel Spence and his column of some 600 men duly marched out of the laager to a position near Galishiwe’s kraal, whilst Cumming’s 400 men moved into position to the right of the hillock known as Galishiwe’s Koppie. At dawn, the centre column of 200 men with their field guns and Maxims began their direct advance on the koppie and by sunrise the stage was set for the assault. It was a complete anti-climax. The rebels had evacuated the koppie days before.

Somewhat surprised, Colonel Dalgety ordered the advance to continue onto a spur north of Gamasep and overlooking Luka Jantje’s village of Derapedi, at the “Fighting Koppie”, as it had come to be called. The first ridge was occupied without meeting any opposition and it was decided that, in spite of heavy losses in the previous engagement in the vicinity, the Fighting Koppie should be stormed almost at once. Accordingly, the guns moved into position 800-1,000 yards from the rebel stronghold and a short halt was called to rest the men. The orders had hardly been issued, however, when Dalgety noticed that the Native Police Contingent was already rushing the koppie.

An immediate advance in their support was ordered and the infantry moved quickly forward, with the rebels initially lying low. On the right flank there was a preliminary skirmish, then a determined effort on the rebels’ part to halt the attack. Prince Alfred’s Guard, in the column advancing on the left, were leading the way, according to one of the men who took part. The rebels had opened fire soon after the infantry had got on the move, but the men kept going steadily and were actually still in sections of fours right up to within about 500 yards of the enemy positions. Then they “front formed” and went right into the battle, which kept up for about another ten minutes of exciting work before there was a flash and gleam of bayonets, as the line rushed the Fighting Koppie with a roar, scrambling up the steep slopes and over the boulders.

Surprised by the suddenness and force of the charge, the rebels turned and fled, but not before Sergeant Hall and Private Mercer of the Kaffrarian Rifles had been killed and Private H. A. Taylor of Prince Alfred’s Guard dangerously wounded. Corporal A. L. Boyle and three of the Native Police were also hit.

On the right flank, the rebels continued to engage the Native Police heavily and, as a Correspondent picturesquely wrote at the time, “the merry rattle of musketry echoed and re-echoed through the valley.” Not for long, however, for after about a quarter of an hour’s further fighting the Native Police drove in the right flank of the rebel positions, whilst the guns bombarded the schanzes near Luka Jantjes’ headquarters. A few shells bursting among the rebels’ wagons caused them to retreat rapidly to schanzes deeper in the mountains, Luka Jantjes himself being cornered. Realising that escape was hopeless, he and a handful of devoted followers opened fire at about 20 yards on men of Prince Alfred’s Guard and the Kaffrarian Rifles, who were moving back towards the water carts. Surgeon-Lieutenant Smythe and Sergeant Bruce of the Cape Police, grasping the situation in an instant, rushed the schanz, and Smythe shot Luka dead with his revolver and disabled one of the rebel chief’s followers who had just killed a Native Police corporal. A third man surrendered, and shortly afterwards the firing died down. It all happened so quickly it seems, that some people thought Luka’s own rifle had gone off and killed him.

With all positions north of Twaaiskloof now in his troops’ hands, Colonel Dalgety decided to keep his men on the mountains throughout the night and then to secure the water in Twaaiskloof before launching an attack on Puduhusche the following day. It was a bitterly cold night and the men suffered considerably without greatcoats or blankets, but at dawn on Saturday, July 31, they were in position dominating Twaaiskloof.

The Maxims and field guns had already been moved up and Colonel Spence’s “Blue” Column, which included Prince Alfred’s Guard, was about to deploy for the assault when, far down the valley, they caught sight of a fluttering speck of white. Soon it was recognised as a white flag carried by a solitary black man, an envoy from Dokwe, now Chief of the Batlapins in succession to Luka Jantjes. Galishiwe was reported to be wounded and hiding in the mountains so, in spite of the white flag, Colonel Dalgety’s advance continued up Twaaiskloof in extended order, with the Native Police and Western Rifles on the heights to left and right and the mounted Dukes well ahead as scouts. By 7.30 a.m. they were in full possession of the rebel laager, Dokwe himself had come in with a few men to surrender and others followed.

Sunday, 1st August 1897, was treated as a day of rest, whilst Dalgety planned his attack on Puduhusche to smash the last elements of the rebellion under Toto. By 10 a.m. the next morning, the advance guard of the mounted Dukes was within 250 yards of Puduhusche Village and had met with no opposition. A message was sent out by Toto offering to surrender and Dalgety replied with an instruction for him to give himself up by next morning. That afternoon at 2 o’clock Toto, the rebel chief of the Batlaros, came in to surrender, and a troop of the Cape Mounted Rifles set off in hot pursuit of the fugitive Galishiwe.

It was only weeks later that Galishwe was finally tracked down to a cave, where he lay wounded and almost starving. Much time passed before he was brought to trial and sentenced to 12 years’ imprisonment, but the fight at Puduhusche really marked the end of the rebellion.

The Bechuanaland Field Force had been on active service for five and a half months and it was nearly nine months since the rebellion had started.

Dalgety’s columns had lost 28 men killed in action or died of wounds or disease; and 36 wounded men had recovered. Quite apart from the Cape Mounted Rifles, the Cape Police and the various Burgher commandos, no fewer than 1,600 men of various volunteer Corps had taken part in the operations, with 185 in all from Prince Alfred’s Guard.

Nearly 2,000 men fell in for a farewell parade at Kuruman on August 13, when they were inspected and thanked by Colonel Dalgety, who had been instructed to break up the Force and hand over to the Cape Police. On 25th August 1897, the Prince Alfred’s Guard Active Service Detachments arrived back in Port Elizabeth, which was gaily decorated to welcome them home. Detraining at North End, they were escorted to the Town Hall by men of their own Corps, the Uitenhage Rifles and cadets. The Mayor, Mr. James Wynne, expressed the town’s pride in their achievements. Mr. W. M. Fleischer, Civil Commissioner and Resident Magistrate, expressed the citizens’ pride in the detachments and read a special message of thanks from the Government.

Major Clark read a congratulatory telegram from the Defence Department in Cape Town, and at a subsequent public banquet in honour of the returned soldiers, the Mayor repeated his congratulations and stressed the achievement of the volunteers in putting down a rebellion without assistance from Imperial troops.

Sir Alfred Milner succeeded Lord Rosmead as Governor of the Cape and High Commissioner for South Africa in 1897, and every day during his visit to Port Elizabeth the Active Service Detachment from the Bechuanaland Campaign provided a guard of honour, under command of Captain Court. Milner expressed his “pleasure at the smart manner in which the various duties of guards and guards of honour were carried out by Prince Alfred’s Guard” in a letter signed by his Military Secretary, Lieut.-Colonel J. Hanbury Williams.

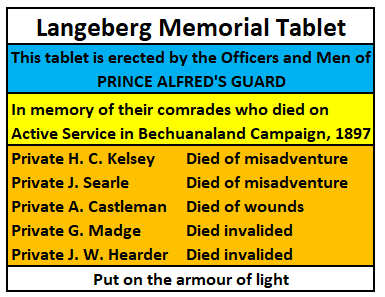

In the Collegiate Church, on Sunday, 5 June 1898, only a few weeks after the re-election of Paul Kruger as President of the South African Republic by an overwhelming majority, with a consequent hardening of Milner’s attitude on the question of Uitlander rights in the Transvaal, Prince Alfred’s Guard paraded at full strength to pay homage to the men who had died in what was the last of the little colonial wars in which the Guards was destined to take part. Within less than 18 months the clash of two different worlds, personified by Kruger and Milner, was to plunge South Africa into a war far greater than anything she had previously known. But on that quiet Sunday in 1898, it was enough that the Guards should have to mourn the loss of five of their comrades at the unveiling of a Langeberg Memorial tablet, simply inscribed:

- Report of Assistant Magistrate at Taungs, C. R. Chalmers, 8 December 1896.

- Defence Report of Commission, published 21 April 1897.

- Dalgety’s Report in Cape Archives.

- Despatch of C.O., B.F.F., 9 April 1897.

- Despatch of C.O., B.F.F., 16 April 1897.

- Hall wrongly states that Gamapedi is at foot of the Langeberg and in Gunners of The Cape, I repeated this error. Author.

- Official Despatch, 29 April 1897.

- Despatch, C.O., B.F.F., B. Ryan’s, 10 May 1897.

- Cape Times, 19 July 1897. Eye-witness account.

- Cape Times, 28 July 1897.

- Cape Times, 2 August 1897 and Official Despatch 30 August 1897.

- Report of Cape Colonial Forces, 1897.

Source

This blog is an almost verbatim account of this battle from the book entitled Prince Alfred’s Guard 1856-1966 by Neil Orpen.