Preceding the arrival of the Dutch farmers in Algoa Bay, intrepid adventurers and naturalists were exploring the area. Amongst this band of hardy individuals was a Swedish naturalist, Carl Peter Thunberg, an apostle of Carl Linnaeus, a Swedish botanist, zoologist, and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming organisms. Due to Thunberg’s discoveries in the Cape Colony, he has been awarded the sobriquet of “the father of South African botany”.

Of all the observations made by Thunberg during his three-year stay at the Cape Colony, two of them resonate with me but for vastly divergent reasons. This is the story of Thunberg’s brief sojourn in the wilderness that was Port Elizabeth in the 1770s.

Main picture: Carl Peter Thunberg in later life

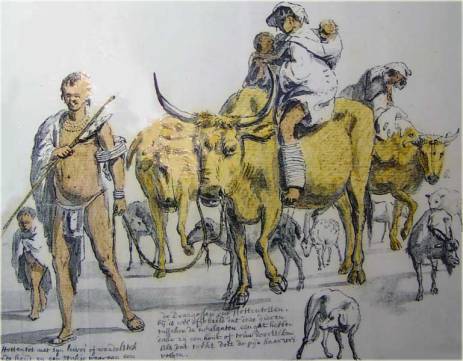

During his stay in the Cape Colony, the Swede managed to perfect his Dutch and delve deeper into the scientific knowledge, culture and societal structure of the “Hottentotten“, the Dutch name for the Khoikhoi, the native people of the southern tip of South Africa. Fortunately for historians, Thunberg’s recorded his travels in the form of a travelogue.

The Khoikhoi were the first foreign culture with which the Swede was confronted. The different customs and traditions of the native people elicited both his disgust and admiration. For example, he considered the Khoikhoi’s custom to grease their skin with fat and dust as an obnoxious habit about which he wrote in his travelogue: “For uncleanliness, the Hottentots have the greatest love. They grease their entire body with greasy substances and above this, they put cow dung, fat or something similar.” Yet, this harsh judgement is moderated by the reason he saw for this practice and so he continues that: “This clogs up their pores and their skin is covered with a thick layer which protects it from heat in summer and from cold during winter“.

Since the main purpose for Thunberg’s journey was to collect specimens for the gardens in Leiden, Thunberg regularly undertook field trips and journeys into the interior of South Africa. Between September 1772 and January 1773, he accompanied the Dutch superintendent of the V.O.C garden, Johan Andreas Auge.

Company Gardens, Cape Town

First Trip to the Eastern Cape

The first trip that Thunberg made was in December 1772. In his book, Travels at the Cape of Good Hope 1772-1775, this journey is covered in pages 100 to 105 by Thunberg. As the terminus of this sojourn was at the Gamtoos River, nothing is learnt about Port Elizabeth per se other than the abundance of game and khoikhoi.

Second Trip to the Eastern Cape

During his second trip, exactly a year after the first, Thunberg skirted Port Elizabeth but execute a Cooke’s Tour of the Kragga Kamma area and an area that I presume is the current Chelsea and Bushy Park. This trip is covered in pages 236 to 244 of Thunberg’s book.

This is what Thunberg has to be say about the trip:

“On the 10th [December 1773], we crossed the Camtous River [Gamtoos River], which at this time formed the boundary of the colony, and which was not suffered to extend farther. [On the road to the Kabeljaus River on the 9th, they came across the last white farmstead belonging to one, Jacob Van Rhenen, apparently a rich burgher in the Cape]. This was strictly prohibited [to cross] in order that the colonists might not be induced to wage war with the courageous and intrepid Caffres [as distinct from the Hottentots] , or the Company suffer any damage by that means. The country hereabouts was fine. and abounded in grass.

Proceeding farther we come to the Looris River, where the country began to be hilly and mountainous, like that of Houtniquas [Outeniquas], with fine woods both in the clefts of the mountains, and near the rivulets. Here and there we saw large pits that had been dug, for the purpose of capturing elephants and buffaloes. In the middle of the pit stood a pole, which was very sharp at the top, and on which the animal is impaled alive, if it should chance to fall into the pit.

The Hottentot captain, who resided in this neighbourhood, immediately upon our arrival, paid us a visit in the evening, and encamped with part of his people not far from us. He was distinguished from the rest by a cloak, made of a tyger’s (sic) skin, and by his staff that he carried in his hand.

On the 11th, we passed Galgebosch [Gallows’ Wood] on our way to the Van Staden’s River where we lighted our fires and took up our night’ s lodging. The Gonaquas Hottentots that lived here, and were intermixed with Caffres, visited us in large hordes, and met with a hearty reception, and, what pleased them most, some good Dutch roll-tobacco. Several of them wore the skins of tygers, [leopards] which they had themselves killed, and by this gallant action were entitled to wear them as trophies. Many carried in their hands a fox’s tail, tied to a stick, with which they wiped the sweat off from their brows. As these people had fine cattle, we got milk from them in plenty, milked into baskets which were perfectly watertight, but for the most part so dirty that we were obliged to strain the milk through a linen cloth.

Inqua village

On the 12th [December 1773], in the morning, we passed the Van Staden’s River, [which he probably forded about 2 ½ kms in a direct line from its mouth] and arrived at two large villages consisting of a great many round huts, disposed in a circular form. The people crowded forward in shoals to our wagon, and our tobacco seemed to have the same effect on them as the magnet has on iron. The number of adult persons appeared to me amount to at least two or three hundred. When the greatest part of them had received a little tobacco they retired well pleased, to a distance in the plain, or else returned home. The major part of them were dressed in calf-skins, and not sheep-skins, like the Hottentots.

Interestingly, these Khoikhoi which Thunberg encountered on the heights, near what was to become Cadle’s Hotel, were in a settlement which Wirgman and Mayo characterize as a “town”. In all probability it was a village, at best, which Thunberg alludes to. Nevertheless, it does disprove the accepted wisdom that all khoikhoi were itinerant vagabonds especially when they intermarried with the Xhosa. Given the types of materials that were used to construct their abodes, there is little likelihood of any “ruins” being uncovered. However, in their book on St. Mary’s church, Mayo and Wirgman do provide additional information to substantiate Thunberg’s claim that there was a settled community in this vicinity. According to these authors, “arrow heads and other Hottentot implements have been found there in such numbers as to show manifest traces of the former Hottentot town”.

Thunberg continues: “We had brought with us several things from town, with which we endeavoured either to gain their friendship, or reward their services, such as small knives, tinder-boxes, and small looking-glasses. To the chief of them, we presented some looking-glasses, and were highly diverted at seeing the many pranks that these simple people played with them: one or more looking at themselves in the glass at the same time, and then staring at each other, and then staring at each other, and laughing, ready to burst their sides; but the most ridiculous part of the farce was that that they even looked at the back of the glass, to see whether the same figure presented itself as they saw in the glass.

These people, who were well made [built, endowed?], and of a sprightly and undaunted appearance, adorned themselves with brushes made of the tails of animals, which they wore in their hair, on their ankles, and round their waists. Some had thongs cut out of hides, and others had strings of glass-beads bound several times round their bodies. But upon no part of their dress did they set a greater value than upon small and bright metal plates of copper or brass, either round, oblong, or square. These they scoured with great care, and hung them with a string, either in their hair, on their foreheads. on their breasts, at the back of their neck, or before their posteriors; and sometimes, if they had many of them, all round their heads. My English fellow traveller had brought with him one of those medallions struck in copper, and gilt, that had been sent with the two English ships, which were at this time sailing towards the South Pole, to be distributed among the different nations in that quarter of the globe. This medal was given to one of the Caffres who was very familiar with us, and who was so very pleased with it, that he accompanied us on the whole of our journey and back again, with his medal hanging down glittering just before the middle of his forehead.

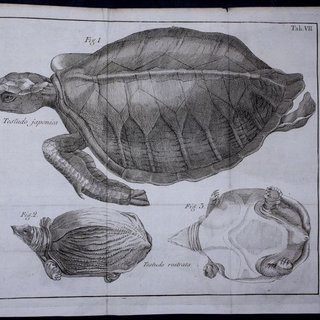

Some of these people had hanging before their breasts a conical skin made of the undressed skin of an animal, which was fastened about the neck by four leather thongs and served them as a tobacco pouch. Some of them wore about their necks a necklace made of small shells, called serpents skulls strung upon a string, and to this hung a tortoise-shell, for keeping the bukku ointment in. Most of them were armed with as many javelins as they could well hold in one hand.

The huts [of the local Inqua khoikhoi populations] were covered over with mats made of rushes, which, with their milk baskets, were so closed that no water could penetrate them. The range of mountains which, during our whole journey, we had hitherto had to the left, now came to a termination. [These were probably the Van Stadensberge]. And to the right of us, was seen the sea. A larger range of mountains, however proceeded farther into the country to the left. [The Suurberge, 75kms north of Port Elizabeth].

The country hereabouts was full of wild beasts of every kind, and therefore very dangerous to travel through. We were more particularly anxious concerning our draught animals which mighy easily be scared away by the lions, and lost to us for ever.

Outspan at Kragga Kamma

We were likewise too few in number, and not sufficiently armed, to protect ourselves against the inhabitants, whose language our Hottentots now no longer perfectly understood. We therefore came to the resolution to entice from this village another troop of Hottentots to accompany us, which we accordingly did, by promising them a reward of tobacco and other trifles that they were fond of, as also to kill for them a quantity of buffaloes sufficient for their support. This promise procured for us a great many more than we wanted, and put troop consisted now in excess of a hundred men.

As an aside, how did Thunberg expect his now redundant khoikhoi assistants to return home? It is inconceivable that he provided food and other victuals let alone any serverance package negotiated with their shopstewards. It is safe to say that employees in Thunberg’s home country, Sweden, would have been treated no better than his treatment meted out to these tribesmen.

The 13th. The country in which we were now were, was called Krakakamma (sic). [This area was defined in 1776 by Swellengrebel as the entire promontory between the Van Stadens and the Zwartkops rivers]. It abounded with grass and wood, as well as wild beasts of every kind, which were here still secure in some measure from the attacks of the colonists. These were chiefly buffaloes, elephants, two horned rhineocetoses, striped horses and asses [zebra and quaggas], and seversl several kids of buck, particularly large herds of hartebeests.

First we travelled to the Krakakamma valley [Kraggakamma Vlei on the old farm Kraggakamma is 6kms south of Greenbushes, still conforms to the same shape as when it was mapped by C.D. Wentzel in 1752], and afterwards from hence farther downwards to the sea shore, where there was a great quantity of bushy growth, as well as wood of a larger growth, filled with numerous herds of buffaloes, that grazed in the adjacent plains.

In the afternoon, when the heat of the day abated, we went out with a few of our Hottentots a hunting, in hopes of killing something wherewith to satisfy the craving stomachs of our numerous retinues. After we had got a little way into the wood, we spied an extremely large herd of wild buffaloes, which being in the act of grazing, held down their heads, and did not observe us till we came within three hundred paces of them. At this instant the whole herd, which appeared to consist of about five or six hundred large beasts, lifted up their heads, and viewed us with attention. So large an assemblage of animals, each of which taken singly is an extremely terrible object, would have made anyone shudder at the sight, even one who had not, like me, the year before, had occasion to see their astonishing strength, and experience the rough manner in which they treat their opponents. Nevertheless, as we were now apprised of the nature of the animals, and their not readily attacking anyone in the open plains we did not dread either their strength or number, but, not to frighten them, stood still a little while, till they again stooped down to feed; when, with quick steps, we approached within forty paces of them. We were three Europeans, and as many Hottentots trained to shoot, who carried muskets, and the rest of the Hottentots were armed with their throwing-spears. The whole herd now began to look up again and faced us with a brisk and undaunted air; we then judged that it was time to fire, and all at once let fly among them. No sooner had we fired, than the whole troop, intrepid as it otherwise was, surprised by the flash and report, turned about and made for the woods, and left us a spectacle not to be equalled in its kind. The wounded buffaloes separated from the rest of the herd, and either could not keep up with it, or else took another road.

Amongst these was an old bull buffalo, which came close to the side where we stood, and obliged us to take to our heels, and fly before him. It is true, it is impossible for a man, how fast that he may run, to outrun these animals. Nevertheless, we were so far instructed for our preservation, as to know that a man may escape tolerably well from them, as long as he is in on an open and level plain; as the buffalo, which has very small eyes in proportion to the size of its head, does not see much side-ways, but only straight forward. When therefore it came pretty near, a man has nothing more to do than to throw himself down on one side. The buffalo, which always gallops straight forward, does not observe the man that lies on the ground, neither does it miss its enemy, till he has had time enough to run out of the way. Our wounded bull came pretty near us, but passed on one side, making the best of his way to a copse, which however he did not quite reach before he fell. In the meantime, the rest of our Hottentots had followed a cow that was mortally wounded, and with their throwing-spears killed a calf. We, for our part, immediately went up to the fallen bull, and found that the ball had entered his chest, and penetrated through the greatest part of his body, notwithstanding which he had run at full speed several hundred paces before he fell. He was certainly old, of a dark grey colour, and almost without any hairs, which, on the younger sort, are black. The body of this animal was extremely thick, but his legs, on the other hand, short.

When he lay on the ground, his body was so thick, that I could not get on him without taking a running jump. When our drivers had flayed him, at least in part, we chose out the fleshiest and pickled some, and at the same time made an excellent repast on the spot. Although I had taken it into my head that the flesh of an old bull like this would have been both coarse and tough, yet, to my great astonishment, I found that it was tender, and tasted like all other game. The remainder of the bull, together with the cow and the calf, were given to the Hottentots for their share, who were not at all behind hand, but immediately made a large fire on the spot, and roasted the pieces they had cut off without delay. What they preferred, and first of all laid on the fire, were the marrowbones, of which, when broiled, they eat the marrow with great eagerness. The guts, meat, and offal, they hung up on the branches of trees; so that, in a short time, the place looked like a slaughter-house; about which the Hottentots encamped in order to broil their victuals, eat, and sleep.

On the approach of night, my fellow travellers and I thought it best to repair to our wagons, and give orders for making our cattle fast, before it grew quite dark. In our way we passed within a few hundred paces of five lions, which, on seeing us, walked off into the woods. Having tied our beasts to the wheels of our wagons, fired our pieces off two or three times in the air, and kindled several fires round about our encampment, all very necessary precautions for our security, as well with respect to the elephants as more particularly to the lions, we lay down to rest, each of us with a loaded musket by his side, committing ourselves to the care of God’s gracious providence. The like precautions we always observed in future, when obliged to encamp in such places where man indeed seemed to rule by day, but wild beasts bore the sway at night. These wild animals for the most part, lie quiet and still, in the shade of woods and copses during the day, their time for feeding being in the cool of the evening and at night, at which time lions and other beasts of prey come out to seek their food, and devour the more innocent and defenceless animals. A lion cannot by dint of strength, indeed, seize a buffalo, but always has recourse to art, and lies in wait under some bush, and principally near rivulets, where the buffalo comes to drink. He then springs upon his back with the greatest agility, with his tremendous teeth biting the buffalo in the nape of his neck, and wounding him in the sides with his claws, till, quite wearied out, he sinks to the ground and dies.

On the 15th, in the morning, I went out to see whether the trees of the woods, of which this part of the country consisted, had yet any blossoms upon them; but found that the summer was not far enough advanced, and that the trees were so close to each other, and so full of prickles, that without cutting my way through them, I could not advance far into the wood, which, besides, was extremely dangerous, on account of the wild beasts. Here, and in other places, where it was woody, we observed near the watering-places, the fresh tracks of buffaloes, as also the tracks and dung of elephants, two-horned rhinoceroses, and other animals.

According to Wirgman and Mayo, this bushy country continued until he reached the shores of Algoa Bay, which was fringed with conical sandhills covered with dense bush all the way from the Zwartkops mouth to Cape Recife. The existence of these sandhills is confirmed in the book by Barrows which depicts these great sandhills which have now completely disappeared. Over time, these bushes were chopped down for firewood and the sandhills which had preciously been anchored by this vegetation, were blown away.

In the plains there were striped horses [zebras] and asses [quagga], hartebeests, koedoes. We therefore got ready and set out for Zwartkop’s River [Thunberg would have forded it above the tidal limit between Perseverance and Despatch] and the salt-pan, not far distant from it, where we waited during the heat of the day. Near this saltpan, as it is called, we had the finest view in the world, which delighted us the more as it was very uncommon. This Zwartkop’s saltpan was now, to use the expression, in its best attire, and made a most beautiful appearance. It formed a depression of about three-quarters of a mile in diameter, and sloping off by degrees, so that the water in the middle was scarcely four feet deep. A few yards from the water’s edge this depression was encircled by a mound several fathoms high, which was overgrown with brush wood. It was rather of an oval form and took me up a good half-hour to walk round it. The soil nearest the valley was sandy; but, higher up, it appeared to consist, in many places, of a pale slate. The whole saltpan, the water of which was not deep, at the same time that the bottom was covered with a smooth and level bed of salt, at this juncture, being the middle of summer and in a hot climate, exactly resembled a frozen lake covered with ice, as clear and transparent as crystal. The water had a pure saline taste without any thing bitter in it. In the heat of the day, as fast as the water evaporated, a fine salt crystallizing on the surface first appeared there in the form of glittering scales, and afterwards settled at the bottom. It was frequently driven on one side by the wind; and, if collected at that time, proved to be a very fine and pure salt. The saltpan had begun to grow dry towards the north-east end, but to the south-westward, to which it inclined, it was fuller; to the westward it ran out into a long neck.

It appeared to us somewhat strange, to find, so far from the sea, and at a considerable height above it, such a large and saturated pool of salt-water. But the water which deposits this salt, does not come at all from the sea, but solely from the rains which fall in spring, and totally evaporate in summer. The whole of the soil of this country is entirely salt. The rainwater which dissolves this, runs down from the adjacent heights, and is collected in this basin, where it remains and gradually evaporates; and the longer it is evaporating the salter it is.

The colonists who live in the Lang Kloof, and in the whole country extending from thence towards this side, as also in Kamdebo, Kankou and other places, are obliged to fetch their salt from this spot.

It was said, that not far from this there were two more saltpans, which however yielded no salt till they were quite dry. Several insects were found drowned in the salt water, some of which were such as I could not meet with on the bushes alive, during the few hours that I stayed here and walked about the copses, which my curiosity induced me to do, although it was a very dangerous spot, on account of the lions.

Our Hottentots, of whom we had now but a few in our suite, and whom we had left to take care of our oxen that were turned out to grass, we found fast asleep, overcome by the heat of the day. Towards evening, we drove a little farther on, and arrived at Kuka, [now Coega] where the brook was already a mere stagnant puddle and only had brackish water in it. Nevertheless we took up our night’s lodging here.

We were surprised to find here a poor farmer, who had encamped in this place, with his wife and children, by stealth; in order to feed and augment his small herd. And indeed these poor people were no less astonished, not to say terrified, at our arrival, in the idea, that we either had, or might, inform the government against them, for residing out of the appointed boundaries. The farmer had only a small hut made of branches of trees for his family, and another adjacent to it, by way of a kitchen. We visited them in their little abode, and, at our request, were entertained by them with fresh milk. But we had not been long seated before the whole basin of milk was covered with a swarm of flies, so as to be quite black with them; and the hut was so infested with flies, that we could not open our mouths to speak. Within so small a space I never beheld, before nor since, such an amazing number of these insects.

We therefore hastened to our vehicles; and having kindled our fires and pitched our camp at a little distance from the hut, listened the whole night to the howling of wolves, [hyenas]and the dreadful roaring of lions.

On the following morning, being the 16th of December, we proceeded to the Great Sunday River, the banks of which were very steep and the adjacent fields arid and meagre.

The major part of our ample retinue of Hottentots had now left us, after having got, in the course of the journey, venison enough to feast on, and, as we were approaching nearer and nearer to a country which would soon be changed to a perfect desert, where no game nor venison was to be hoped

Salient points

The area in the vicinity of Port Elizabeth was already inhabited in 1772 – albeit sparsely – 50-years prior to the arrival of the 1820 settlers. The main inhabitants were Inqua khoikhoi interspersed with the occasional Xhosa tribesman.

Another surprising point that this piece illuminates, is the quantity and diversity of wild life, especially of the megafauna variety, which were domiciled in this area. As the Dutch farmers advanced over the Gamtoos River and settled in Algoa Bay, they steadily hunted the large animals to extinction such that by time that the 1820 Settlers passed through, no mention is ever again made of elephants, rhinoceroses or buffaloes except for a small head of elephants in the Alexandria area which had eluded the predations of the big game hunters.

Sources:

Travels at the Cape of Good Hope by Carl Peter Thunberg (1986, Van Riebeeck Society, Cape Town)

The Collegiate Church of Parish of St. Mary Port Elizabeth by Archdeacon Wirgman & Canon Cuthbert Edward Mayo (1925, Longman Green & Co, London)