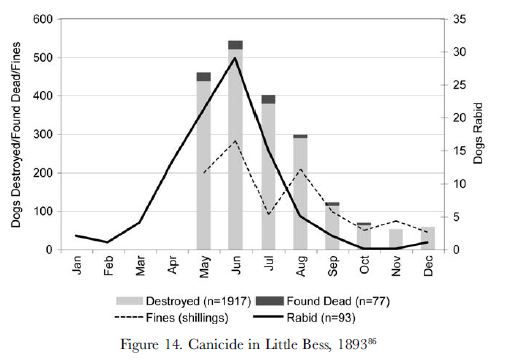

Over a period of several decades, the dog had been transformed from an animal into a pet, a mongrel into a pure-bred. Thus, the threat of mass canicide to obviate the menace of rabies in 1893 was met with implacable opposition by these canine owners. By the time that the harsh restrictions such as muzzling and tethering were relaxed in December 1893, 1,917 dogs had been destroyed and one human died, Lydia Gates.

Yet again, class played a prominent role in how the epidemic was dealt with.

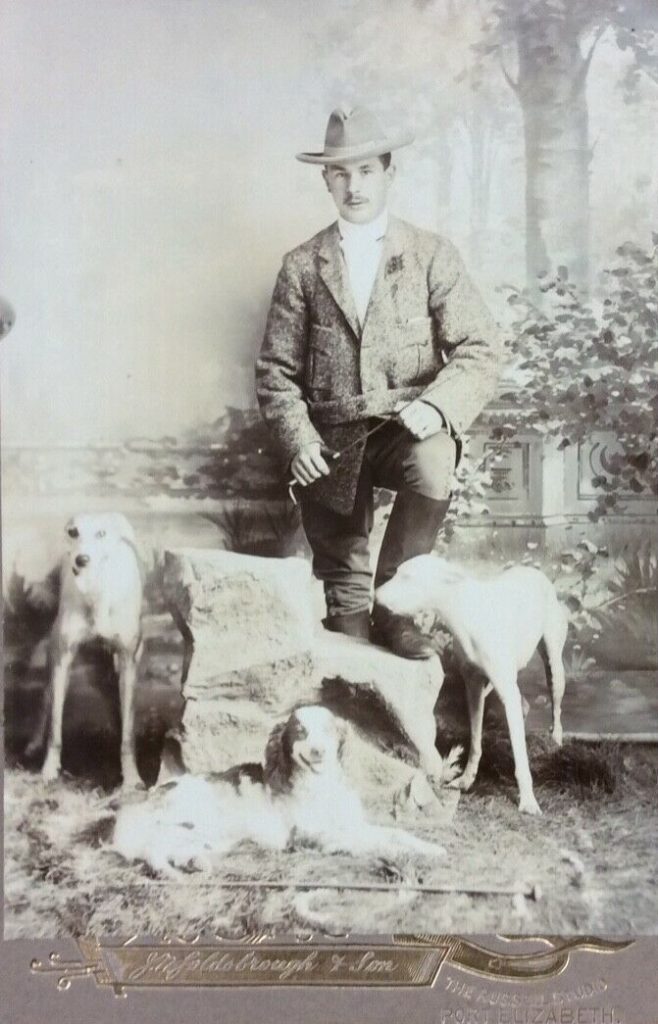

Main picture: Prize dogs in Port Elizabeth in 1895

Disease and the pet

Initially the Cape Colony was devoid of any veterinarian services and the Colony’s dog population, like its livestock, generally suffered from poor health. Dogs were not allowed the run of the house and their home was outside. The level of treatment for diseases was abysmal, dependent upon the owners’ quackery and bush remedies, many of which were less than useless, to divine and treat symptoms. Scourges such as distemper regularly ravaged dog populations while many were afflicted by mange, worms and other non-lethal pathogens.

The concerns of South African Kennel Club were focused more on cruelty than on disease. Similarly, the emphasis of the town’s SPCA was on comfort. Thus occasionally dogs in poor physical condition and even manged dogs were displayed at the annual dog show which formed part of the Agricultural Show.

From Canis Familiaris to Canis Populi

From the early 1880s, the public veterinary service, with its focus on livestock, and not on domestic animals, was already sounding the alarm regarding the danger of importing rabies into the colonial dog populations but this was refuted by the conventional wisdom which was conjectured that the virus could not cross the equator. The proposal advocating the quarantining of all imported dogs was met with fierce resistance as it threatened to disrupt travel and sport of the imperial and local settler elites. Hence this practice was confined to commercial livestock species only.

The popularity of dogs was evident in the 350% surge in the number of dogs between 1875 and 1891 as opposed to the increase in humans by only 80%. The explosion in the canine population by the early 1890s was reflected in shopkeepers keeping water bowls outside their doors, spectators at St. George’s Park complaining of the disruption of cricket matches and the local police acquiring a stray as a mascot. However, it was the 400 tons of dog faeces that the sanitation department had to collect annually that drove the Town Council to enforce the licensing regulations more strictly. In the same vein, they added dog-catching and poisoning to the duties of the Inspector of Nuisances in 1887. The target of their effort was the stray.

Rabies strikes

As if to allay the fears of the residents, these dog owners were under the mistaken belief that the epitome of canine progress, the pedigree dog, could not harbour disease nor pose a threat to the town. Thus when they commenced dying in numbers in April 1893, poisoning was suspected and not rabies. It was only when a dog belonging to a committee member of the SAKC was affected that the town veterinarian, Britton, was called in and diagnosed suspected rabies on 21st April 1893. Fortuitously, the Colonial Veterinary Surgeon was in town. He supported Britton’s suspicion.

The Town Council acted with alacrity, ordering all dogs to be muzzled for three months commencing on 3rd May 1893. Furthermore, they ordered the canicide of the rest of the dogs. A safety net was drawn around Port Elizabeth in the form of a quarantine cordon. All dogs were forbidden to leave whether by road, rail or sea whereas all imported dogs first had to be quarantined on Robben Island.

Race and class exposed in the midst of the crisis

Partially reflecting the class and race prejudices of SAKC, a Sunday raid on a native location rounded up and exterminated all its dogs, both licensed and unlicensed, on the grounds that they were unmuzzled. In response, Elijah Modoloma raised a valid objection: [Are] only the native people’s dogs ….. subject to rabies and Hydrophobia? If not, why are the white people’s dogs permitted to roam at large without being muzzled, many of which may be seen in the streets today …. We … think that a bite from a white man’s dog is as bad as that from a natives’s.

The local press exposed the authorities’ bias and hypocracy against the dogs of the underclass by reporting that the dogs of the middle class had remained unmuzzled yet no such drastic action had been taken against them. The conceit employed was to allege that the middle-class owners took more interest in their pets and hence would be aware of any ailments prevalent in their animals.

The National Dimension

This situation was to change drastically once Parliament reopened on the 22nd June 1893. The view of the farming members of Parliament were not as indulgent as their livestock regularly faced being culled whenever epidemics arose. Moreover, they were unsympathetic and unmoved to the middle class’ ruse of claiming a special dispensation due to the monetary value of their pets as if the farmers’ livestock was of lesser value to the agricultural community.

Man with his dog

An adamant MP, Arthur Douglass from Grahamstown forcefully stated the stockholders’ views as follows: “There was only one way of grappling with this matter and stamping out this dreadful epidemic among dogs, and that was to slaughter every dog in the Port Elizabeth division (hear, hear and much cheering). We believed in dealing with this matter at once and severely. We should be sorry for the dogs and their owners, but the concern was for public health.”

As if this was insufficient to stick in the craw of the middle class urbanites, he then made his disdain for urban mores and sensibilities, as Sittert put it “urging all haste to prevent owners [from] smuggling dogs out of the town and rejecting compensation as a dog was kept as a luxury, not as a means of livelihood, like horses and cattle and vines, for the destruction of which compensation had to be given.”

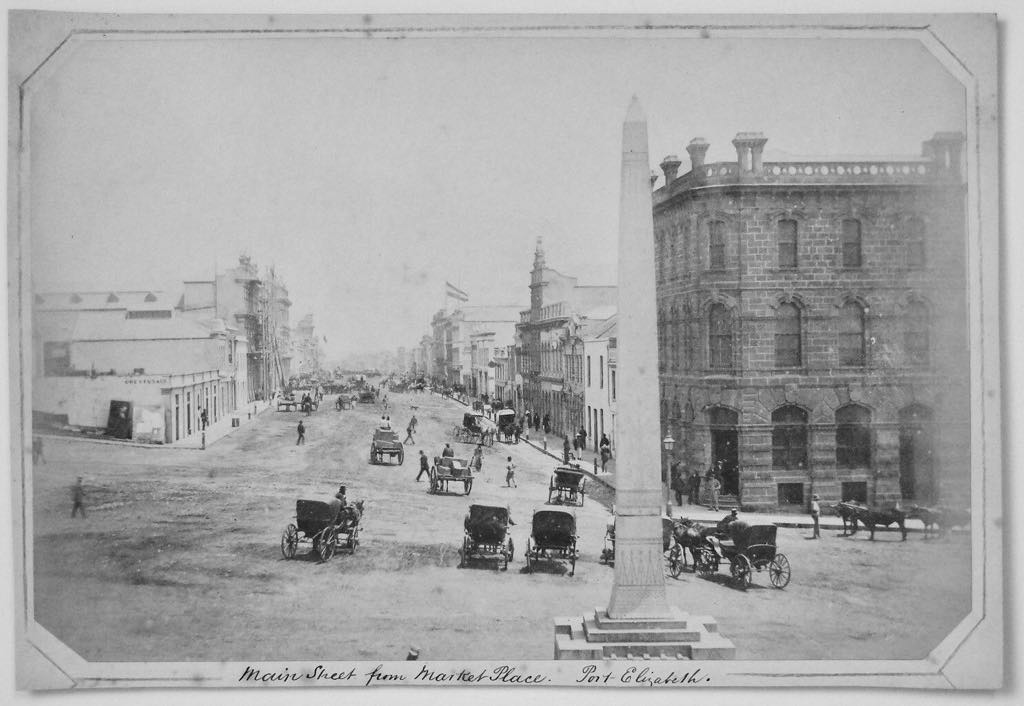

This unapologetic vitriolic speech must have struck a chord with fellow farming members who were in the majority in the house. In response, they resolved to produce a Canicide Bill within 24 hours mandating the destruction of all dogs in Port Elizabeth. Without a risk of being melodramatic, panic and pandemonium set in within Port Elizabeth’s middle class. A hastily convened meeting chaired by the President of the SAKC, Dyason, was held post haste, at noon that same day at Armstrong’s Auction Mart on the corner of Main and Donkin Streets

Local counter offensive

Councillor Hume’s comments encapsulated the mood of the crowd when he stated that “Some people had dogs, which were not only valuable for what they are worth, but they had a sentimental value attached to them. Some people had great attachment for their animals, and they would regard Mr Douglass’ proposal in the same way that the order of Herod was regarded in the olden days.” Hume now reiterated the nub of issue as far as the middle class was concerned. “To destroy their dogs would be like destroying their children. It would be a great grief to him to see his dogs destroyed.”

Faced with the prospect of being compelled to take their own medicine, the middle class hastily relented and consented to muzzling and chaining of their canine pets. With the whiff of a threat of civil disobedience in the air from PE’s canine owners, when parliament met on the 23rd June, it also relented by substituting the pitiless term “genocide” for “confinement”. Both parties had drawn back from the brink and cooler heads had prevailed. The differences in the views in the House reflected their sensibilities. The views of the rural members who held that it was “better that a hundred dogs or ten thousand dogs, should die than one man” were juxtaposed by their town colleagues who “acknowledged that human life was valuable, but there were also many dogs which were highly prized, and of which their owners were very fond.”

The rural MPs probably rolled their eyes in befuddlement at the notion that sentimentality played a role in urban morality and the sway that they held in the House. Being suitably chastened, the Municipal muzzling order became law on the 23rd June with Mounted Cape Police enforcing the quarantine order. A month later, the Rabies Act was promulgated requiring all dogs to be permanently muzzled and chained with a fine of £50 for delinquent dog owners, a King’s Ransom in those days. Even the Divisional Council felt chastened as they voluntarily and expeditiously reimposed the long defunct Dog Tax of 5s per capita at the end of August.

Yet another blow was struck against the dog owning class when 13-year-old low born, Lydia Gates, died from rabies. This event “hardened the popular mood against further indulgence of the middle class and its pets.” The Herald further opined that “We trust [that] we shall now hear the last of the specious special pleading in favour of the poor dog.” Moreover, the Herald urged that “an example [be made] of those owners of dogs who are systematically defying the law” through “a heavy fine or two.”

Diminishing returns

For the succeeding three months, the mongrel hordes were largely cleared from the streets of the town as they were principally the focus of the increasingly vigilante atmosphere. With the mongrel foe vanquished, it was now the turn of the middle class pooch. The sights of the enforcers were now set on their new foe. Into this smorgasbord was thrown race, class & privilege. The dog owners’ “true and lawful rights” of property, privacy and person was “brutally violated” in having Hottentot and African Inspectors enter their homes in order to earn their 1s bounty for every unmuzzled and unchained canine.

In response, some owners smuggled their dogs upcountry while others on Richmond Hill continued their open defiance of the regulations relying on their status to intimidate dog catchers and police into inaction. For the majority, they were intimidated into full and utter compliance with the regulations. What they did vociferously object to was Hottentots demanding access to houses without their husbands being there to chaperone them as they combed the house and property for dogs in breach of the regulations. Apart from ladies at home alone, they demurred at killing puppies and braining unmuzzled dogs. In decrying the seizing of a prize fox-terrier bitch in late July 1893, they forged a cause celebre. The dog’s owner, Chapman, sought damages amounting to £20 damages from the Town Council as he deemed the poisoning the dog ultra vires. Chapman’s lawyer, J.A. Chabaud argued that scavengers – by which he in fact meant dog catchers – did not possess the power to violate private property. On losing the case, Chabaud appealed to the Supreme Court which upheld the magistrate’s initial verdict that these regulations were indeed valid based upon the principle of salus populi suprema lex esto, – “The health (welfare, good, salvation, felicity) of the people should be the supreme law“, a maxim or principle first postulated in Cicero‘s De Legibus.

They were thoroughly stymied.

Unintended consequences

With a dwindling pool of mongrel dogs, the dogcatchers’ pay declined. Being remunerated on a unit basis, this raised the spectre of ever declining paychecks. In response, in between the rumblings about short pay, they were forced to catch agile felines and push ever harder on the reluctant white middle class. In raising the bounty per animal to 1s 6d, the dog catchers homed onto their last readily available source of delinquent canines – the indignant middle class.

Even in such gruesome circumstances, is evolution prevalent. In fact it is expedited. The feral dog population became ever more elusive and fickle in their attempts at survival so as to defy all attempts at extirpation. Generally the urban population was in support of the culling of its mewling feral feline population with their out-of-tune caterwauling. The decline in the feral cat pool had an unintended consequence, as they always do. A plague of rats menaced the town. Two other ramifications came to the fore. The theft of dogs for their bounty, which was previously unheard of, now became pervasive. The residents also reported a surge in criminality which was ascribed to their dogs being shackled and thus precluded from performing their guard dog role. Whether this tale was apocryphal or not, or whether it was yet another mechanism to force the Council to relent in their quest to target their well-bred dogs, shall never be known.

The SAKC once again took up the cudgels of the pet owners. Supported by the Council, they repeatedly petitioned the Department of Lands, Mines and Agriculture to rescind the chaining order in mid-October 1893. Finally in mid-November, the Department relented by lifting the chaining order and a month later, the muzzling order too, just in time for the much needed Christmas holidays. This was a pyrrhic victory as isolated cases of rabies occurred throughout 1894, prompting the government to ban the annual dog show and re-impose the muzzling order from August to December 1894.

1895’s dog show was not hosted, despite official blessing being bestowed upon it, due to the reluctance of all venues to permit the use of their premises. By 1896, the horse had metaphorically bolted. Rival shows had sprung up across the region, supplanting the SAKC’s monopoly and the centre of gravity was shifted elsewhere.

Source

Class and Canicide in Little Bess: The 1893 Port Elizabeth Rabies Epidemic by Lance van Sittert