These recollections are those of a Mr Josephus Winter who occupied various civic positions during his 82 years.

Main picture: Mr Josephus Winter

Curriculum Vitae

Josephus was born on 26th June 1849. He commenced his career as a carpenter, serving his apprenticeship with Messrs. Passmore & Murrell, leading builders of that early period. After joining with a Mr Allen, they founded the well-known firm of Allen & Winter, Builders and Contractors and with whom he was in partnership until May 1881.

Winter was a Divisional Councillor for thirty years commencing in 1896. Apart from this, Winter was also a City Councillor as well as being a member of the Boards of the Technical College, the Provincial Hospital and the School Board.

Baakens lagoon filled in

Within the span of his memory, the town grew from a village to an important city. In his youth, North End was barren veld and the Hill was an open expanse of farmland while Humewood was a string of windswept sand hills. The waves of the incoming tide used to wash high up the Baakens River valley into the wide lagoon that separated the centre of town from the South End. This lagoon was a favourite boating and yachting centre. There was still a drift across the Baakens River.

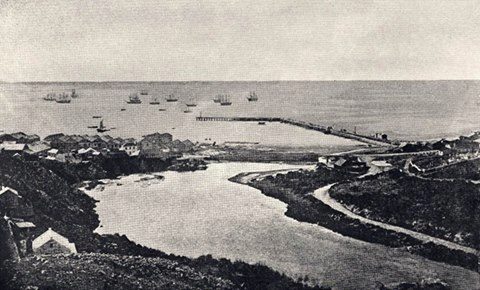

The Baakens River lagoon

It was only in the early 1880s that actions were taken to reduce the area of the lagoon. It so happened that Allen & Winter were contractors for Standard Bank building and the Lombard Chambers in Main Street had recently been demolished . The work necessitated a huge amount of excavating at the foot of the hill below the Donkin Reserve. A problem arose in disposing of this unwanted stone and sand. With the consent of the Town Council, it was agreed to dump this debris into the northern fringe of the water. As the work progressed the lagoon was gradually narrowed down. Instead of adopting a view regarding the long term preservation of this natural feature so close to the centre of town, they viewed it as a method of raising additional money by way of the sale of the reclaimed land.

Early view over the Baakens River

Another problem facing the Council was the huge quantities of sand washed down off the Hill every time that there were torrential downpours. Having acceded to the request to permit the lagoon to be utilised as a dumping ground, this practice was extended to the disposal of this soil.

Water supply

Winter can recall that water for early Port Elizabeth was only obtainable from a number of wells and springs. One of these was situated in Rudolph Street from which it was piped to a water boat moored some distance from the shore in order to supply shipping. To satisfy the demand in the town itself, wells were sunk at various locations: in the Market Square at the foot of Military Road, in Donkin Street, Russell Road and Constitution Hill.

Clearly the research performed by John Snow into the causes of cholera had not yet reached the Cape. Evidence of this was the lack of sanitation whereby the drainage from cesspools and dirty sluits on the plateau above the town used to pollute the water supply at the foot of the hill. The Settler stock must have been made of stern stuff as cholera outbreaks were largely unknown.

Frames Reservoir on Shark River

Finally in the 1860s, the town embarked upon its first real water scheme. This involved erecting a dam on the Zak or Shark River and piping the water to town. There was tiny miscalculation in the plan; by then, the town had commenced its ascent of the Hill with the toffs finding refuge there away from the plebeians below. Much to the chagrin of this vociferous segment of the residents, the water pressure was such that it was only sufficient to force it six feet above Main Street.

Even when the scheme was announced which involved the construction of three reservoirs – the Van Stadens, the Bulk River and the Sand River Dams – the recommendation was only passed by the ratepayers by ONE vote.

Shipping and the harbour

In Winter’s youth during the 1850s and 1860s, the age of steam ships had not yet supplanted the sailing ship. As such, Port Elizabeth, was still a regular port of call for windjammers ie large sailing ships, built to carry cargo for long distances in the nineteenth and early twentieth century.

Ships at anchor in the Bay

Port Elizabeth was even fortunate to have two sailing vessels registered here. They were owned by John Owen Smith and undertook regular voyages between Algoa Bay and Mauritius. Smith named them “Emily Smith” and “Edith Smith” after his two daughters. Being vessels of 250 tons capacity, there were not very large. From Port Elizabeth, they exported dried fish, salt extracted from North End Lake, salt beef and tallow wrapped in sheep skins. Tallow is a hard fatty substance made from rendered animal fat, formerly used in making candles and soap. These ships returned from Mauritius laden with consignments of a sweet white crystal – sugar.

The sea wall from the jetty

The construction of the sea wall was commenced in the late 1850s. Apparently the landing place for fishing boats was where the Railway Institute was later built. Here there was a sandy spot between rocks. The Municipality permitted the dumping of rubbish on this section of the beach thereby reclaiming the strip of land on which the Railway Station is now built.

Sinking of the Charlotte

One of Winter’s most vivid recollections was the wrecking of the troopship “Charlotte” while on her way to India in 1856 with 163 officers and men of the 27th Regiment, together with 11 women and 26 children. A howling south-easter sprang up and at about 4 o’clock in the afternoon, the “Charlotte” parted from her anchors under the terrific strain of the huge seas running in the Bay.

Winter describes the scene as follows: “I remember the hundreds of people standing along the seafront at the foot of Jetty Street and to the north and south, waiting for what they knew had to come. Even above the fury of the wind and sea, we could hear the cries of the women and children as the “Charlotte” tried vainly to make her way against the wind, while we on the shore waited in horror near the foot of Jetty Street, the rockiest part of the foreshore in the whole Bay, about an hour and a quarter after parting from her anchors and just as it was getting dark.

Charlotte, Algoa Bay carrying the 27th Regiment driven ashore near Jetty Street Port Elizabeth 19 September 1854

It was terrible. In quite a little time, she broke clean in half and the water seemed to be black with the heads of people struggling in the waves. The survivors were taken in by various people, and I remember the people in Mr. Ashkettle’s house. The dining room table and floor were covered with the bodies of grown-ups and children who had been drowned, and for weeks after the wreck, bodies were being washed ashore.”

Developments on the Hill

Furthermore, Winter recalled that in the 1870s, buildings had only just breasted the hill up which Russell Road ran. From there it was only a short distance to being in the wild. It was then that a certain Mr Bain sought solitude from the maddening crowds of the bustling town of Port Elizabeth in a country residence in Park Lane which would ultimately be converted into Nazareth House.

Unlike today, Richmond Hill only had a single lonely farmhouse occupied by Mr Hartmann. Likewise, the northern end of Queen Street [around Cooper’s Kloof, present-day Albany Road] still possessed a stretch of boggy ground covered with fields of white arum lilies. Nearby was a market gardener and finally there was a brewery in the vicinity.

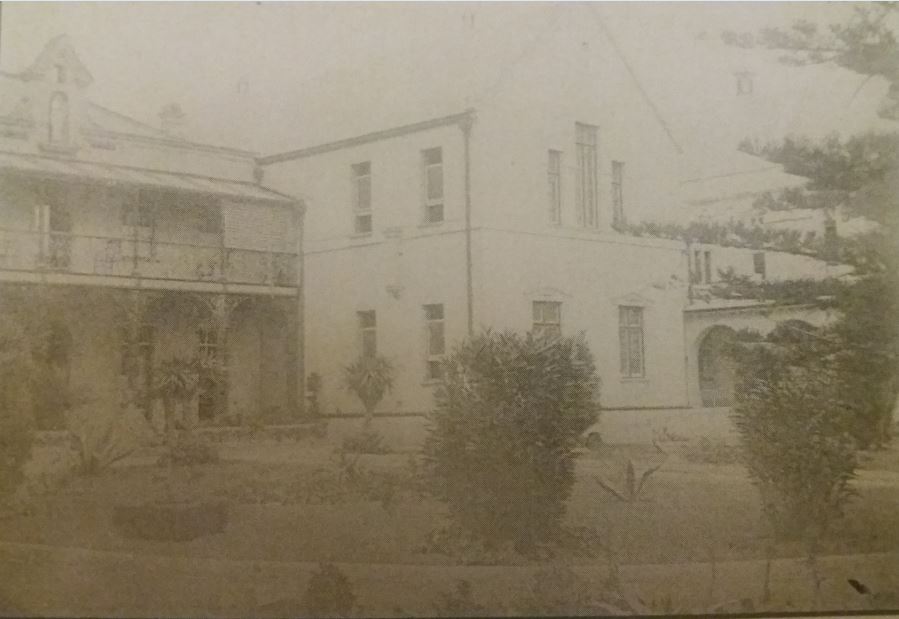

Samuel Bain’s House in Park Lane, built in 1875 on the left. Now part of Nazareth House

Even though the construction of White’s Road was commenced by Mr Fancourt White in 1850 – that is one year after Winter’s birth – Mr Winter could still recall as a child that the precipitous incline known as Constitution Hill was still considered the main route up the hill. Furthermore he remembered a track starting from the present day Public Library which then wound its way beside the Donkin Reserve to the top of the hill where it emerged at the corner of the site now occupied by the Edward Hotel. Until White’s Road had been constructed with convict labour, this track was the sole means of access to the top of the hill.

Donkin Reserve circa 1870

It was not until the construction of the various main roads up the hill such as White’s, Russell and Albany Roads, that the development of the Hill began in earnest. Just to indicate how little the property on the hill was worth prior to its development, Winter provided the example of Jewish Synagogue site in Western Road. This was pertinent to Winter as that property, being vacant, was considered to be of such minor value that the owner neglected to pay the rates and taxes. When the long arm of the Town Council caught up with him, he was obliged to sell the property to extinguish his debt. It was Mr Winter who purchased the entire property for the amount of the rates due to the Council.

Pearson Street – Looking down the road from Whitlock Street

Toll Roads

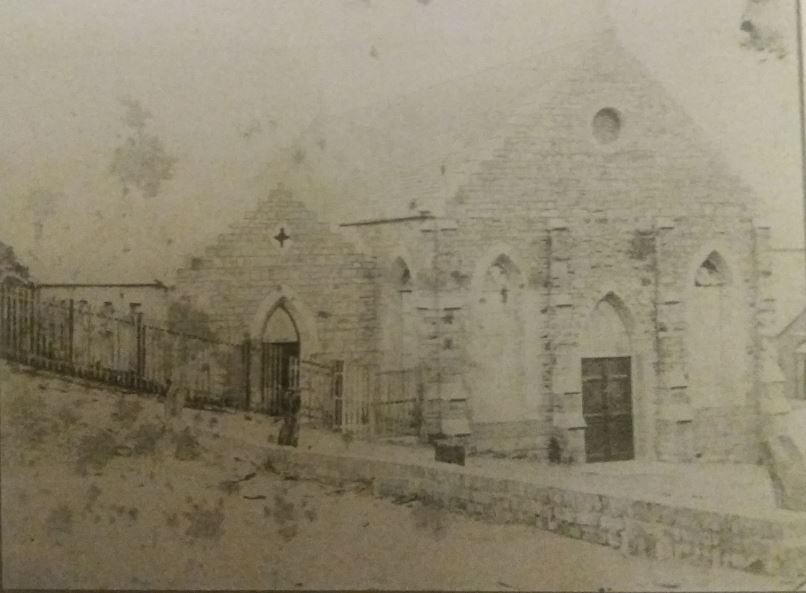

Another archaic method of financing the upkeep of the roads in those days was the expedient of tolling roads. This was a lucrative source of revenue for the authorities. The main users of these tolled roads were the wool farmers who brought their produce from as far as the Free State to be exported from Port Elizabeth’s harbour. There were four toll gates being Queen Street where the original Baptist Church stood, Cape Road, Uitenhage Road and Grahamstown Road.

Queen Street Baptist Church opened in March 1858. Closed in 1959

The demise of the Queen Street and the Uitenhage Road tolls, arose with the opening of the railway between Port Elizabeth and Uitenhage in 1870. Winter was involved in this venture in an unusual way in that he was a member of the Port Elizabeth Volunteer’s Band that played martial music when the first sod of the railway line was turned at Swartkops. The Midland Line which was constructed some time later, connecting Port Elizabeth to Kimberley, was a significant boost for Port Elizabeth as it was natural port for Kimberley was Port Elizabeth.

Allure of diamonds

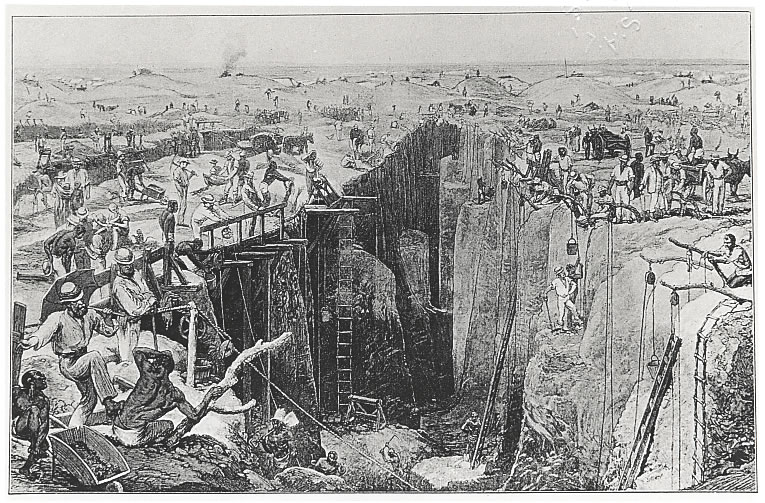

Like many other local residents, in 1869 at the age of 20, Josephus Winter together with his friend, Thomas Morgan, sought his fortune on the diamond fields at Kimberley as the allure of making a fortune overcame him. Like most diggers, they were rapidly disabused of the notion that this back-breaking work was the road to riches. Instead during their sojourn in Kimberley, between them they had only discovered one gem of miniscule value.

Diamond mining in Kimberley

Both sheepishly and rather red-facedly returned home empty-handed. To their mortification, they learnt that on the very spot on which they had camped for several days, a huge pipe of diamonds was discovered. This excavation is now renowned as the Big Hole of Kimberley.

What is a pity is that Winter kept a diary for fifty years but it has been lost. How much more detailed would those notes have been about Port Elizabeth shortly after its birth.

Source

A Century of Progress. The Story of the Divisional Council of Port Elizabeth. 1856 – 1956 by J.J. Redgrave M.A. (1956, Nasionale Koerante Beperk, Port Elizabeth)

Hi Dean, I would love to make contact with you regarding your Kruger walk back in 2014. Please would you e-mail me? Txs so much!