Originally intended by John Paterson as a tombstone to his business partner and friend, George Kemp, but when rejected as inappropriate by Kemp’s family, it was salvaged and placed in Market Square where it majestically stood for 58 years. Instead of connoting its initial conflicted sepulchral/royal origins, it should have been dedicated to Paterson himself, who could, if you will, be characterised as Port Elizabeth’s greatest son.

This is the story of that saga.

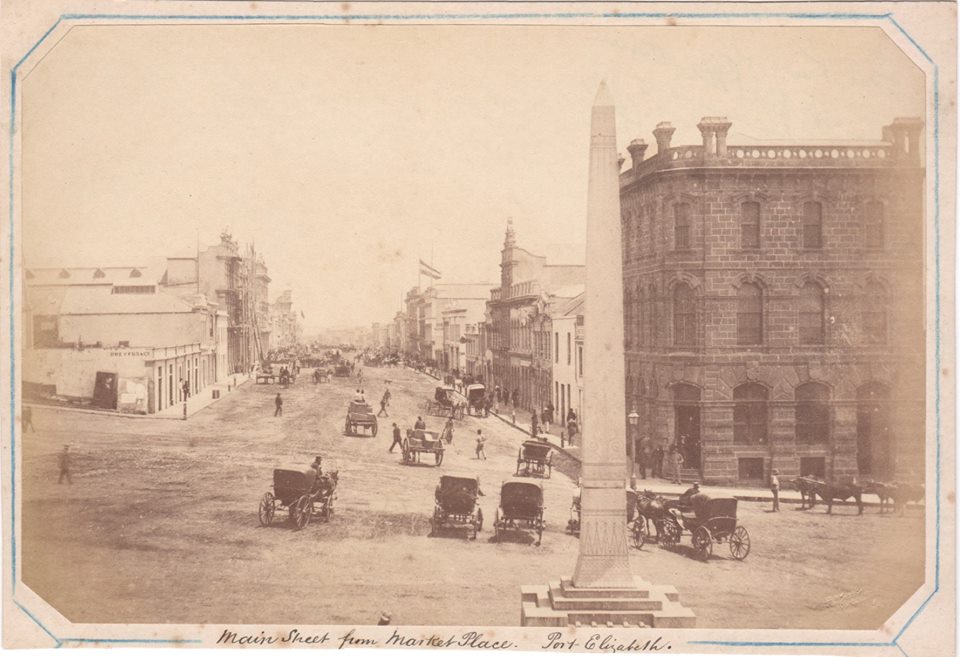

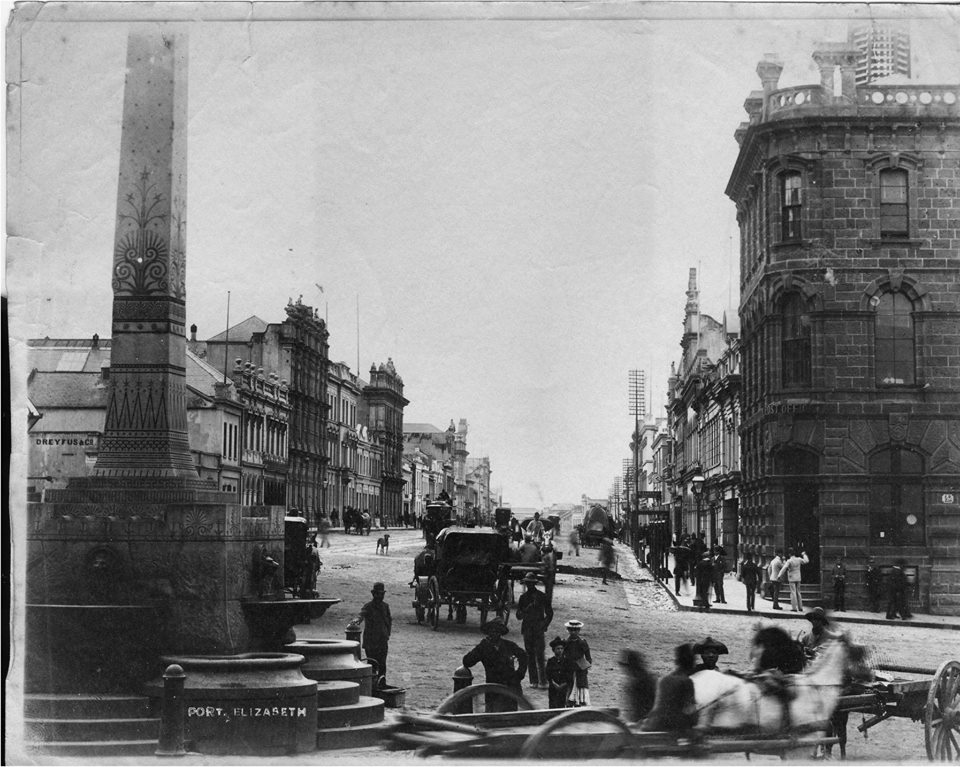

Main picture: The obelisk with its prominent position in Market Square

Business ventures

After a successful teaching and business career in Port Elizabeth, new horizons beckoned for the driven, enterprising Paterson. To expand his business, he had been travelling overseas for the past three years: 1859 to 1862. After an extensive tour of England and the Continent, it is surmised that he made a sizable trip to America. It was probably in 1860 that he visited Boston amongst several cities to consolidate his American ties.

As well as managing the London side of his firm Paterson, Kemp & Co, in his ongoing quest to make valuable contacts which would be used to promote the three companies that he had founded in London during this time – the Standard Bank of British South Africa, the South African Irrigation and Investment Company and the Eastern Province Railway Co.

It was at an Exhibition held in London in November 1862, that Paterson espied the beautiful tall tapering piece of Abberdeen granite obelisk on show. In all likelihood, Paterson was attracted to it because it came from Aberdeen, his home town, and because his partner, and brother-in-law, George Kemp, had recently died, that his usual impetuosity overwhelmed him. Without hesitation and thinking through the consequences, Paterson, while still mourning the loss of his friend, purchased the obelisk. His intention was to erect it as a tombstone on the grave of George Kemp in St. George’s Park as an act of homage. This item was manufactured at Brest, France by Messrs. Pollen Bros. It was an excellent example of monumental art and was made of a stone known as “trap,” an igneous rock similar to granite. Prior to his return to the Colony, Paterson arranged that the heavy, clumsy object be shipped out on the barque Rose of Montrose to Port Elizabeth on the 16th February 1863. Paterson himself arrived back in Port Elizabeth, some weeks prior to the arrival of the obelisk.

Sequence of events

Hardly had the obelisk arrived in Port Elizabeth on the 25th April 1863 than controversy arose. This stemmed from the raison d’etre for having the obelisk displayed in Market Square. In 1921, Mary, Paterson’s daughter, after yet another bout of vitriolic correspondence raging in the Port Elizabeth newspapers, wrote to her niece in Cape Town in order to dispel all the myths swirling in the public discourse.

By all accounts, it was George Kemp’s father who put a spoke into the wheels of erecting this monolith on his son’s tomb. Apparently he was furious, even incandescent maybe, if rumours are to be believed. In stern tones, he declared that George had been but a plain merchant and as such, that instead of an ostentatious monument, a plain white cross would be more fitting. It is told that the Grandpa Kemp advised Paterson to “throw that damned thing in the sea.” Grandma Kemp was equally opposed to the idea and claimed that such a heavy stone would sink in the grave. Instead of fulsome praise, Paterson had been comprehensively vilified when the Kemp family had looked the gift horse in the mouth.

Even Mary Paterson was to add her belated voice to the controversy by adding that “As far as I am concerned, it might well have been thrown in the sea. It was a white elephant from the first and the money might well have been better spent on the family.”

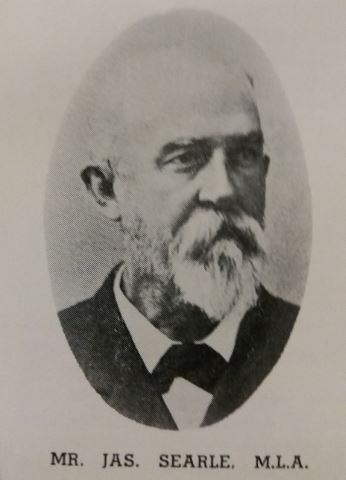

James Searle’s account

Hardly had Paterson been rebuffed by George’s father than the Rose of Montrose with the unwanted chunk of stone, would belatedly arrive in Algoa Bay. It was one matter to ship the huge lump of stone out on the Rose, but quite another matter to disembark it onto an unstable skiff in the Bay and then land it on the beach.

An account of how this laborious task was effected, is still extant. Posterity has been enriched by James Searle’s version of this event. James recalled that “George Kemp died in October 1862. Paterson, who happened to go to England, bought the stone at some exhibition, I understand, with the intention of placing it on Kemp’s grave. Old Joshua Kemp was a fine type of gentlemen, a good old sort, now almost extinct; one of the white beaver top hat and alpaca jacket breed. He was opposed to it from the start on the grounds that his son was not a public man, simply a merchant. And so a white marble tomb was substituted, and there it is besides Paterson’s wife on the west side of the Scotch burial ground.”

“Now comes the joke. In the meanwhile, the stone had been shipped on the barque Rose of Montrose in London with the clause ‘to be taken by ship by the consignee at his risk and expense and to find all gear.’ At that time, I worked one of the boats, but was generally sent on any special job. So after a lot of quibbling, I was sent off to rig the gear and to make ready to put the stone out. I went afloat in the afternoon, and it was late when I got the gear rigged. Seeing [that] it was such a fine night, on my own responsibility, I guaranteed the men a double day’s pay, if they got the thing out.

“So they got a lighter alongside and put it over. In those days, there were no appliances for heavy lifts. So we used to beach the boat at high tide and wait till the tide receded to discharge the boat. We got the boat on the beach, and when she was fast, went home. The Superintendent and I lived up Walmer Road opposite each other. On the way I tapped on his bedroom window and told him what I had done. Instead of getting any kudos, he told me [that] I had missed the opportunity of making a good tip as no one wanted the damn thing, and being night, I could have quietly slipped it overboard.

Anyhow I always reckoned [that] it was the best day’s work I ever did in Algoa Bay. I was young then and had some go in me, and landing that stone, made me a Superintendent in 1865. Well, the stone remained on the beach as a white elephant until the Prince of Wales got married later that year. A happy thought struck some loyal Johnny and it was given to the town. It is all bosh about not being able to get it up White’s Road. White’s Road was finished long before Prince Albert landed here in 1861, when we in the Naval Volunteer Brigade marched up like the loyal Britons we were, headed by old Harreden’s band.

An elegant solution

There it lay, unwanted on the beach. No one, including Paterson, wished to incur the expense of transporting it to a site in the town. It was the marriage of the Prince of Wales – Prince Albert – to Alexandra of Denmark on 10th March 1863 which came to the rescue. When the Council met to discuss the plans to celebrate this marriage, Paterson found a solution to the obelisk problem. Paterson magnanimously offered it to the town as a monument to commemorate this festive occasion. A special Marriage Festivity Committee was formed and told to erect it in the town. The Committee in turn contracted its erection in the town square to a Mr James Wyatt who was paid £105 to do so.

On 9th May 1863, a letter appeared in the Telegraph from the Town Clerk:

Gentlemen,

I have the honour to inform you that at a special Meeting of the Town Council held this day, the following resolution was agreed to: “that a deputation from the Festivity Fund Committee be informed that the Council will have much pleasure in taking over from the Festivity Fund Committee, the obelisk, now lying on the beach, and will remove and erect it in the Market Square at the cost of the Municipality in commemoration of the auspicious marriage of H.R.H., the Prince of Wales.”

Archibald,

Town Clerk

To the Rev. J. Harsant, T. Wormald and W. Bent

(Deputation from the Festivity Fund Committee)

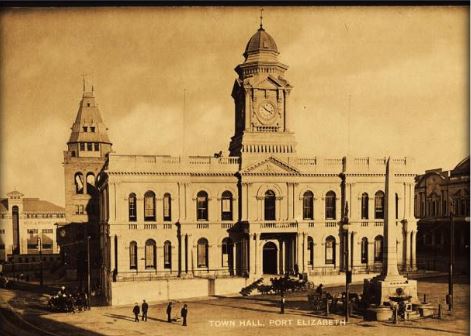

Celebrations

The date of the festivities, as they were referred to, was set for Friday 22nd May 1863. Like other such celebrations, the town would take it to heart. As dawn broke on this day, the stores in Main Street and the Town Hall were gaily decorated with bunting and other decorations. But the focal point of the celebrations was – as the correspondent of the Eastern Province Herald described it – a “somewhat sinister shrouded stone.” This “stone” hung from a tripod above the hole which had been dug for its base. Finally the correspondent berated its appearance as it bore “an unfortunate resemblance to a corpse hanging from a gibbet.” This sarcastic comment was probably amongst the first of a litany of disparaging comments.

The procession formed up at the appointed hour. It then proceeded to march along Main Street to the cheers of the citizens. Without a doubt, Marizza, Paterson’s recent bride and second wife, was participating in the celebrations but not as a member of the procession. In all likelihood, she stood in the window of her husband’s store, Paterson, Kemp & Co, in Main Street, watching the contingent pass with unbridled pride in her heart. The destination of this throng was the “shrouded stone” standing in front of the Town Hall. As the march approached its destination, it ground to a halt around the obelisk surrounded by a cohort of Free Masons in full regalia. After a short laying ceremony performed by the Goodwill Lodge of the Freemasons with H.W. Pearson deputising for the Master, S.W. Fairbridge, the obelisk was unveiled to much cheering.

A feast was spread on long tables in the street. John Paterson made a speech and someone called for cheers for the Prince and Princess and again for Paterson. One wit remarked to much cheering, “Paterson was cheered and then the Prince.”

Later years

This would never pacify the malcontents, disaffected and those simply dyspeptic of nature. For some, the obelisk was an object of derision while for others it was dignified artefact and a bond to their homeland, England. It was in this vein, that the public discourse would be ventilated from this date onwards with opinions sharply divided.

It was only during 1878 that the obelisk would receive its final accoutrements. It was then that the drinking fountains and troughs were erected around the base of the obelisk. Apart from the practical aspects of these items as drinking troughs for thirsty horses, they also complemented the obelisk visually.

By the 1920s, with controversy still swirling regarding the rationale for this monument, the Council moved that an inscription be attached to the obelisk stating why it had been erected. At the meeting, Mr. Young found it incongruous that a tombstone should be used to celebrate a wedding.

In the early 1920s, the Obelisk was finally banished and together with its handsome base of lions and watering troughs. On 2nd February 1921 the Council decided that the obelisk should be removed and replaced by a howitzer. This cannon would serve as a memorial to members of the S.A. Heavy Artillery who had lost their lives during WW1. On the 4th and 5th March 1921, the obelisk and troughs, unwanted yet again, were placed in a Municipal yard, where they were gradually broken up. One of the troughs found its final resting place at the Walmer Town Hall and the pointed top, cleaned and polished, for a period graced a private home in the Town. The fate of the other water troughs is unknown and probably found a home as a bird bath in some municipal employee’s home.

In the 1960s as part of the Historical Society’s plan – subsequently abandoned – to restore as much of Cradock Place as possible, they suggested that it be erected at Frederick Korsten’s former home.

During October 1969, the ultimate fate of the obelisk was placed in the hands of the P.E. Museum. In lieu of a favourable verdict, pending a decision re-erection, the obelisk was dumped down in the municipal yard in Harrower Road, where a member of the Historical Society found it and had it transferred to the museum where its final resting place is as a gate guard outside Bayworld Museum in Humewood. On the 6th May 1975, the obelisk was re-erected at the museum.

Postscript

In March 2018 two historians proposed moving the Obelisk from Bayworld and re-erecting it on the Donkin Reserve in front of the historic Grey Institute building, as Paterson and his achievements had not been properly recognised in the city. The suggestion apparently did not meet with much support, maybe partly due to cost implications.

En passant

According to Pierre Jordaan “The water trough used to stand in Forest Hill in the 60s and 70s. I studied architecture at UPE and did a project on the snake park’s new building. I noticed the obelisk there and informed the museum that the water trough was standing in Forest Hill – I don’t know whether they followed it up, but later I was pleased to see it in front of Walmer Town Hall. At the time it was thought that the other troughs ended up as rubble for the construction of the flyovers”.

In a Facebook post, Willy de Wit states that “Today I went to Walmer and had a look at the trough . Amazingly this piece of marvel is made out of a single piece of rose granite , polished to near mirror finish . One would be hard pressed to find someone , today , who would be willing or capable of reproducing such a masterpiece . Mind boggling!“

Sources

One Titan at a Time by Pamela FFolliott & E.L.H. Croft (1960, Howard Timmins, Cape Town)

Article entitled The Obelisk Again in the section headed ‘Gallimaufry’ in the September 1970 edition of Looking Back.

Article entitled Lofty plan for Donkin Reserve in The Herald, 3 January 2018.

Photos of the current location of one of the water troughs was supplied by David Raymer

This is very interesting but in the first paragraphs you write “1963” when I think you mean 1863.

Hi Sara

Thanks for that correction. You are totally correct.

Dean

The water trough used to stand in Forest Hill in the 60s and 70s. I studied architecture at UPE and did a project on the snake park’s new building. I noticed the obelisk there and informed the museum that the water trough was standing in Forest Hill – I don’t know whether they followed it up, but later I was pleased to see it in front of Walmer Town Hall. At the time it was thought that the other troughs ended up as rubble for the construction of the flyovers.

Hi Dean

Do you have any knowledge of two iron carronades that once stood at the Walmer town hall ?.

I bought one from an elderly gentleman in Westering, who said he obtained it in the 1930,s.

He said they were dumped at the municipal store, and he took one and a colleague the other.

My gun is about a meter long.

Regards

Malcolm Turner