Most of what is nowadays known as the Eastern Province was devoid of whites prior to the arrival of the 1820 Settlers. Notwithstanding that fact, a sprinkling of intrepid Dutch farmers did farm in the area between the Gamtoos River and the Great Fish River. By all accounts, it was a precarious existence at best. Not only were they at the mercy of marauding bands of indigenous tribesmen but they were also in danger from large predatory animals.

In spite of all these clear and present dangers, numerous indomitable adventurers also traversed this treacherous landscape. One such person was Henry Lichtenstein, a German medical doctor and a professor of natural history at the University of Berlin.

This is his story as recorded in his book entitled Travels in Southern Africa in the years 1803, 1804, 1805 & 1806.

Main picture: Henry Lichtenstein

Background to the situation prior to Lichtenstein’s expedition

The preceding twenty-five years before the arrival of the British settlers in 1820 were unsettling, as the area had already experienced the first two of the so-called Frontier Wars. Furthermore, the British seized control of the Cape Colony in 1795. The Trekboers were very disgruntled with the British government and revolted, declaring Graaff-Reinett a Republic in 1799. To quell this uprising, the British despatched a small military force to the eastern Cape Colony under the command of General John Vandeleur. The revolt was settled without a shot being fired.

With this military contingent readily available on the eastern border, the British government then decided to utilise it to expel the Xhosa from the Zuurveld – in future to be known as the Albany District – and so began the Third Frontier War. Vandeleur successfully removed the Gqunkwebe from the Zuurveld and then dispatched most of his force back to Cape Town. Simultaneously many of the Khoi servants who had been mistreated by the Trekboers had fled to the east and lived among the Xhosa. Shortly after Vandeleur had reduced his military force, the Xhosa and former Khoi servants attacked the eastern Cape Colony and advanced as far west as the Langkloof.

The British once again sent a military force to the Eastern Cape along with a prefabricated blockhouse to Algoa Bay. Honoratus Christiaan David Maynier, the landdrost or magistrate of Graaff Reinett, sent a commando to join the British. Together they forced the Xhosa back across the Fish River. This war came to an end in 1803 when the Dutch again assumed control of the Cape Colony.

Excursion to Algoa Bay

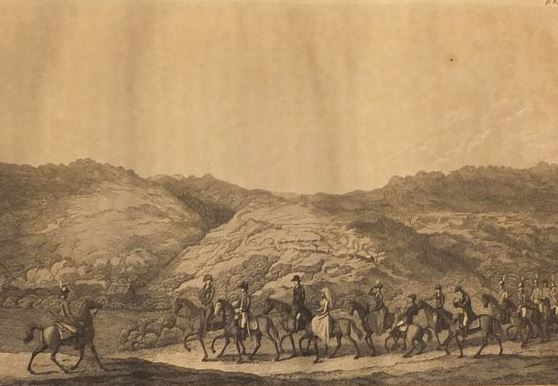

The route followed by Lichtenstein to Algoa Bay was not by sea but rather overland via Swellendam and then through the Langkloof. Their cuisine was spartan, often comprising the hunting of plentiful wild game. As they exited the Langkloof, Lichtenstein’s party encountered the first of many destroyed farmhouses, the work of the marauding Xhosa bands.

Lichtenstein records that on the 5th January – presumably 1804 – at about noon, they arrived at the dwelling of a certain Michael Ferreira at his farm called Leeuwensbosch – Lion’s Bush. The house was in a state of partial ruin having recently suffered the depredations of a Xhosa attack. To Lichtenstein’s observant eye, the secluded ruined farmhouse with its pious owners, faithful slaves and contented Hottentot [Khoikhoi] servants, was a pitiful sight. As usual, they partook of a frugal meal with their hosts.

Ferreira then gave them two muskets, which some deserters from the 9th Battalion of Waldeck Jaegers had either sold to one of his neighbours or left behind when they deserted. Apparently, this occurred in February 1803 when a contingent of the Dutch Army was encamped upon the Weinberg. A whole squad (piquet) of mercenary soldiers, all Poles, absconded by night. They were part of a contingent of Poles who, having been in the employ of the French Service, were taken into the pay of the Batavian Republic in 1801.

Here was a group of deserters with a profound lack of geographical knowledge but with a cunning plan. Their stratagem was simple: head northwards and, in a few weeks, they would be back in their home country of Poland. Needless to say, for the most part, they were captured by the Colonists and returned to camp. For their paucity of geographical knowledge, they were not merely to obtain a failing grade. They also received the ultimate sanction: the death penalty. Against the odds, five of them did escape from the Colony but that begs the question of what ultimately happened to them. It is speculated that perhaps they met their fate at the hands of the Xhosa tribesmen. It is possible, though highly unlikely, that a few might have even reached Zululand but none would have reached Portuguese East Africa.

In short, it seems that all died in their vain attempt to desert.

Lichtenstein pressed ever eastward and onward. Their next objective was the farm of a widow, Kretzinger [sic], on the Kabeljau River where they were met by Field Cornet Ignatius Muller, with a new voorspan. During a rain-drenched journey, Lichtenstein’s team again passed many houses, which had been destroyed, by marauding bands of Xhosas. During this journey, they even met various bands of itinerant Xhosas, chiefly females, who begged for presents of tobacco, beads and brandy. Amongst these vagabond bands was the sister of the chief Conga who was distinguished not only by the greater splendour of her dress but also by her handsome countenance.

Crossing the Gamtoos River

From now onwards, the going was flatter as they crossed first the Kromme River and then finally the Zeekoe River to arrive at the largest river in the area, the Clmmttoo – the modern day Gamtoos River – where a treacherous crossing awaited them. In the early 1800s, the Gamtoos River marked the eastern most boundary of the Cape Colony. Shortly after crossing the river mouth at low tide, they arrived at the Field Cornet’s farm.

The next day, a torrential storm exploded above them, making conditions slippery and enervating.

Lichtenstein was most impressed by the lush vegetation, lakes and forests abounding in this area. Besides that, herds of elephants roamed freely in these parts. Their guide, a man by the name of Niewkerk [sic], proclaimed that he had shot a large male elephant in that area no more than a week previously.

That night, the guides swopped stories of elephant hunts in the area. Furthermore they confirmed that the elephants became even more prolific the further east they travelled.

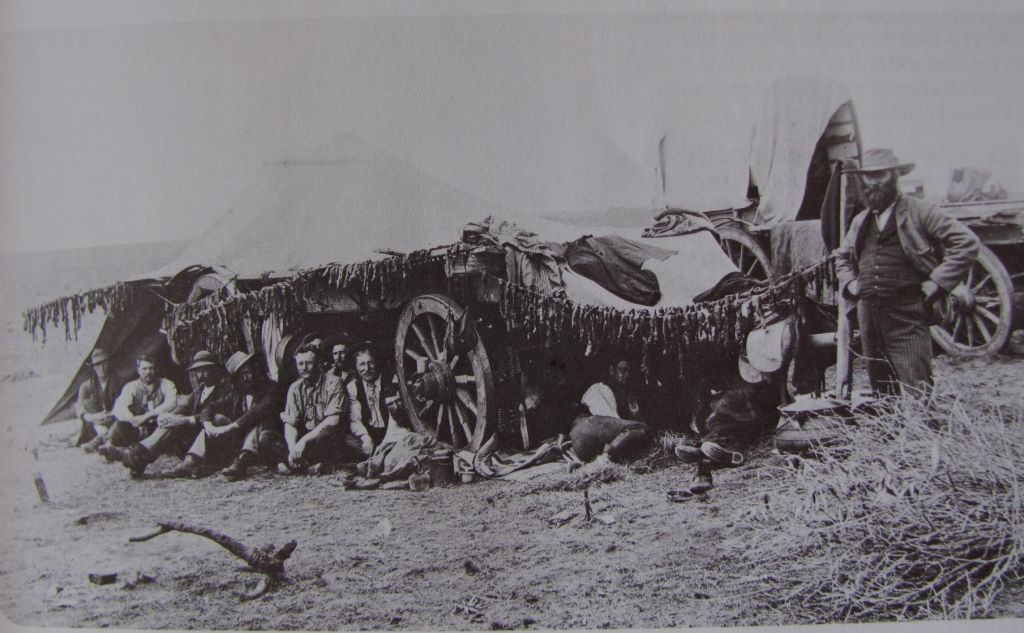

An elephant hunting party was arranged. As the bush was too dense in parts, they reluctantly returned empty-handed after reaching as far as a tributary of the Van Stadens River. An elephant herd was spotted on the opposite bank of the river but given their state of exhaustion and the impending storm, they returned to the party camped in the middle of a forest called Galgebosch.

With the weather threatening to break, they set off for an area called Rietfontein, which is on the eastern bank of the Van Stadens River. It was in this area that Field Cornet Muller owned a house where they could outspan for the night.

Having ridden ahead of the wagons, they were hospitably welcomed by Muller and his wife. The greater part of the house had been destroyed by the Xhosas during the Third Frontier War. So in these cramped quarters, the Lichtenstein Party, the Muller family with their six children and a female relation in labour were forced to reside overnight while waiting for their wagons.

Sleeping outside was not an option as the rain had been falling steadily all day. Due to the lack of space, even the available rooms contained incongruous articles such as dry firewood, a chopping block and two freshly slaughtered sheep. Adding to the incongruity were some half-naked slave girls preparing the meal.

With the rivers and spruits in flood, the wagons battled with the river crossings. In light of this and the fact that their estimated time of arrival was only some indeterminate time in the future, the Commissary-General determined that they would proceed to Algoa Bay while Lichtenstein remained behind to await the rest of the party.

This is the actual Witteklip after which the Witteklip Station in Van Stadens is named and which can be seen from the station. Part of the rock is flat from elephants rubbing against it. At the moment, there is a pair of owls nesting there. Early wagon trains used to camp around the rock on their way to Algoa Bay from the Cape

Lead Mines at Van Stadens

While they awaited the arrival of the wagons, Lichtenstein undertook an excursion to the fabled lead mines on the farm of one Christian Vogel on the banks of the Van Stadens River. The residence itself was in ruins but here they encountered an old slave of Vogel who was dutifully guarding his employer’s cattle.

That afternoon, Lichtenstein returned to Riet River & the homestead of Muller. Here they were assailed by a group of itinerant Xhosas requesting brandy and tobacco. These bands of peripatetic Xhosas, were an annoyance not merely because of their solicitious behaviour but due to the fact that they would kill large quantities of game not for food but for sport.

Arrival in Algoa Bay

Early the following morning, the party, including the wagons, set off for Algoa Bay. From the forests and woods, they emerged onto a flat dreary plain largely devoid of woods as it was of hills. During the latter part of the journey along the main wagon track to Algoa Bay, they even encountered some sand hills, which were extremely fatiguing to traverse.

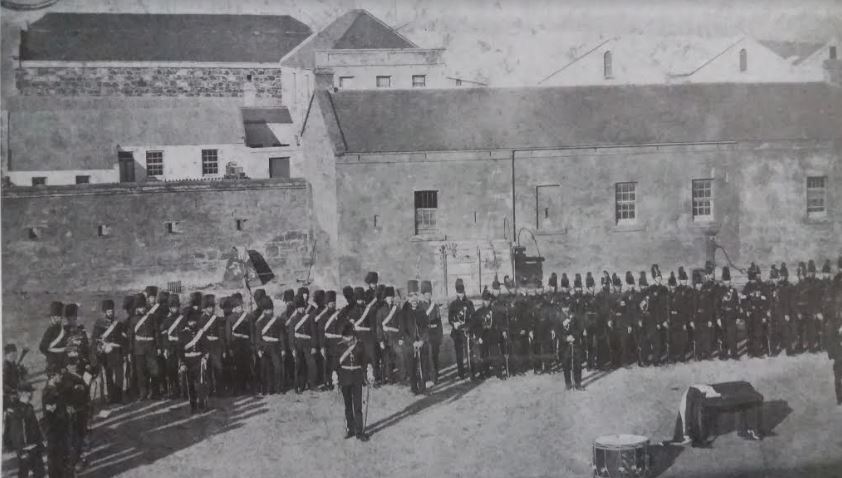

On the final hill, which goes down to the shore, they arrived at an English fortification, Fort Frederick, which had been constructed in 1799. It consisted of a quadrangular wooden blockhouse, surrounded by a wall of the same shape. Beneath the wall was a strong row of palisades and a broad dry ditch.

Eight guns, being 12-pounders, commanded the shoreline and protected the buildings nearby which comprised the barracks, magazines and guardhouses. Westward of the hill on which the Fort stands, was a deep gulley with a little stream called the Baakens River. At a ford towards the mouth of the river, which was concealed between the hills that rose on either side of it, was a wooden blockhouse. In Dutch, a baaken signifies a mark, a stone or beacon of stone set up as a boundary. The river served as a mark for the sailors to identify the landing place; hence the river’s name.

The individual components of the wooden blockhouse were constructed in Cape Town and then shipped by sea to Algoa Bay. It served a dual purpose as a prison and a guardhouse. Between the blockhouses lay, strewn on the hills, extensive barracks for soldiers and a magazine for provisions. Yet another magazine was utilised for military stores and field equipment. Alongside these buildings were the smith’s shop, a bake house, a carpenter’s workshop and sundry other small buildings. The strong powder magazine was located within the fort itself and is still there today.

Several small houses had been constructed in the neighbourhood for the officers among which the house for the Commandant – Alberti – was the most distinguished. It comprised four rooms and was surrounded by a pretty garden.

Under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Alberti, the garrison itself comprised a company of eighty men from the Jaeger Company of the fifth battalion of the Waldeck Regiment. Amongst their non-military duties, these men cultivated bread-corn, potatoes & some sorts of pulses.

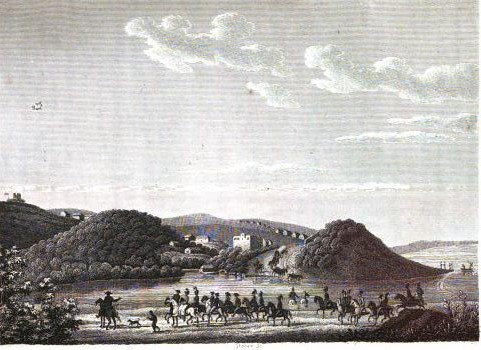

Lichtenstein noted that “the bay in size, form and situation, exceedingly resembles both Plettenberg Bay and Mossel Bay. As it is open to the southeast wind, which blows here for a great part of the year, it offers no secure anchorage to shipping. Indeed the entrance is difficult even when the wind blows from other quarters, particularly the south-west. The landing-place is a little sandy beach near the mouth of the Baakens River. Excepting this, the whole strand is dangerous on account of the reefs. The surf is from the nature of the coast everywhere so strong, that it costs immense labour to bring the goods on shore from the vessels.”

Furthermore, Lichtenstein also noted that “notwithstanding these impediments, this place is now completely erected into a military establishment. It has even been selected for this purpose, because, on account of the impediments, it can so easily be defended against the landing of an enemy. Going along the strand, a short mile eastward of the Baakens River, we come directly opposite the little island of Santa Crux, which lies a quarter of a mile from the shore, but it is only inhabited by seals and penguins. Bartholomew Diaz erected the Holy Cross here in January 1487 and gave the island its name.”

“The country about Algoa Bay is by nature so fertile, that even if uninhabited, it would produce wood, game, salt and grass for feeding cattle in abundance. Now since it has been cultivated by Europeans in quiet times, it produces corn and fruits of all kinds, and even wine. The breeding of cattle prospers so much that meat, milk, butter, soap and other articles dependent upon this part of husbandry, are to be had at very low prices. The bay itself, from the plenty of fish that it produces, offers an abundant supply of food to the inhabitants of its shores.”

“What renders this establishment, however, of particular importance is its situation so near to the borders of the Caffre country – the Xhosas.

Furthermore Lichtenstein noted –presumably when he was fording the Zwartkops River – that “a mile from hence, at the place of the widow Schepers, ground had already been laid out for a Drosty and a village adjoining to it, which is to be the centre of a new district to be called after the family name of the Commissary General – Uitenhage. The Commandant Alberti administered the office of landdrost of this new district as long as the colony remained in the hands of the Dutch.”

Finally, before departing Algoa Bay, Lichtenstein visited a missionary settlement known as Bethelsdorp. The missionary in charge of the “disconsolate rabble of 200 to 300 Hottentots was a priest by the name of Van der Kemp. These vagrant souls had been collected together by him in a vain attempt to convert them to Christianity. Due to their lack of industry” – as Lichtenstein alludes to their indolence – “they lived a life in penury and destitution.”

On account of the poverty and wretched situation of the institution, it was known in the neighbourhood, by way of ridicule, as Bedelaarsdorp, (Beggars’ Village) instead of Bethelsdorp. The Commissary-general donated five hundred Dutch guilders from the government chest toward its upkeep and support.

Lichtenstein was clearly not impressed either with Van Der Kemp or the residents of Bethelsdorp as he bemoaned what he saw as their self-created destitution and lackadaisical approach to neatness and personal hygiene. He reserves special vitriol for Van der Kemp himself for lowering his standard to that of those he sought to help.

Lichtenstein then proceeded to the Zuurveld and the border areas.

Source:

Travels in Southern Africa in the years 1803, 1804, 1805 and 1806 by Henry Lichtenstein

Related blogs:

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Captain Jacob Glen Cuyler

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Captain Jacob Glen Cuyler – A Man of Many Parts

Port Elizabeth of Yore: The Growth of the Population

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Murders most Foul

Port Elizabeth of Yore: The Phoenix Hotel

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Echoes of a Far off War

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Main Street in the Tram Era

Lost Artefacts of Port Elizabeth: Customs House

The Great Flood in Port Elizabeth on 1st September 1968

Port Elizabeth of Yore: The Great Flood of 1st September 1968

A Sunday Drive to Schoenmakerskop in 1922

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Horse Drawn Trams

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Trinder Square

The Sad Demise of the Boet Erasmus Stadium

Interesting Old Buildings in Central Port Elizabeth:

The Shameful Destruction of Port Elizabeth’s German Club in 1915:

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Shameful Torching of the German Club in 1915

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Cora Terrace:

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Cora Terrace-Luxury Living on the Hill

Port Elizabeth of Yore: The Grand Hotel:

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Whaling in Algoa Bay:

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Whaling-From Abundance to Near Extinction

Port Elizabeth of Yore: White’s Road:

Port Elizabeth of Yore: The Slipway in Humewood:

Port Elizabeth of Yore: King’s Beach:

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Russell Road:

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Russell Road-Formerly Burial or Hyman’s Kloof

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Sand dunes, Inhabitants and Animals:

Port Elizabeth of Yore: The Horse Memorial:

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Target Kloof:

Port Elizabeth of Yore: The Road through Target 3Kloof & its Predecessors

The Parsonage House at Number 7 Castle Hill Port Elizabeth

Port Elizabeth of Yore: The Parsonage House at No. 7 Castle Hill

What happened to the Shark River in Port Elizabeth?

A Pictorial History of the Campanile in Port Elizabeth

Allister Miller: A South African Air Pioneer & his Connection with Port Elizabeth

Allister Miller: A South African Air Pioneer & his Connection with Port Elizabeth

The Three Eras of the Historic Port Elizabeth Harbour

The Historical Port Elizabeth Railway Station

The Friendly City – Port Elizabeth – My Home Town

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Russell Road Methodist Church – 1872 to 1966

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Russell Road Methodist Church – 1872 to 1966

The Royal Visit to Port Elizabeth in 1947

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Main Street before the Era of Trams