The fact that the whole tip of the peninsular formed by the southeastern part of Port Elizabeth comprised a huge swathe of sand dunes is now totally lost to its current inhabitants. Commencing in the late 1800’s, a scheme was instituted to prevent the further northern spread of these dunes.

This was their death knell. Today some dunes, a remnant, are still visible at its extremities of Sardinia Bay, the western extent of this dune field, and around the Cape Recife area whilst the driftsands incubator itself, lost its battle for primacy.

This is the story of their demise.

Main picture: Sardinia Bay, a remnant of a once vast sand field stretching inland through Bushy Park to Humewood

Imagine being one of the 1820 Settlers arriving at a forlorn hamlet adjacent to the Baakens River mouth. Standing where the City Hall is now located, the vistas would have been golden sandy beaches bordering the sea, as far as was visible. Looking southward from the top of the hill or preferably from Emerald Hill, one’s eyes would have gazed at the sweep of a huge sand field, with moving dunes, some of which were claimed to be thirty feet high.

Sand dunes at Wood Cape similar to Drift Sands

Today, all that remains of this veritable Wonder of Nature are patches of sea sand. Ultimately, the area annotated as De Duine on early maps by Dutch itinerants, had ineluctably succumbed to the predations of civilisation. Based upon the settlers’ irrational fear that these dunes were ultimately envelope the settlement on Algoa Bay’s southern lip, it was decided to “reclaim” it; in other words destroy it.

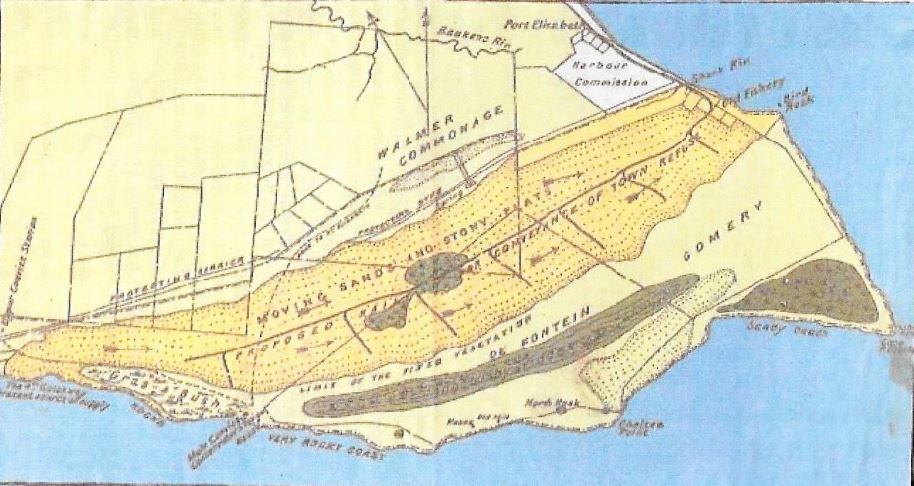

Map of the Driftsands with Gulchways being west of Schoenmakerskop

Like all such sand fields, none is static. Within a few hours, the prevailing winds could transform a high dune into a long flat mound or eliminate it completely. That is the nature of a vast fluid field of sand.

Wind-blown bodies of sand were continuously being swept inland covering more than twenty-two square miles of ground. Glutchways, just west of Schoenmakerskop was the primary source of this sand.

Map showing the earliest subdivisions of farms in Port Elizabeth (J J Redgrave)

During 1870, it was believed that the sand dunes between Schoenmakerskop and Port Elizabeth were drifting eastward towards the Bay and that the drift was becoming a danger to the Harbour itself. This viewpoint was partially predicated on the fact that the Fisheries between the Harbour and Cape Recife were already buried under the sands.

My contention is that this assumption was flawed. It is probably trite to mention that even the early maps of the extent of the drift sands indicated that the Fisheries formed part of the area marked as De Duine. Hence it was not unexpected that given the mobile nature of these dunes, that the area around The Fisheries would at some point be engulfed by the dunes.

Joseph Storr Lister

Furthermore, I contend that this area had been stable for thousands of years. As such, what would cause it to shift to encompass the harbour, which were a few kilometres north of its normal range? Because of this defective reasoning, this treasure of nature was doomed.

By 1872, the Harbour Commissioners were empowered to use funds to stabilise the dunes and purchase land affected by the sand. The initial part of the Harbour Board’s reclamation work was executed under the supervision of William Stephen Webber. Webber and his family moved to Governorskop, named after the location at Bushy Park where the Governor of the Cape Colony, Sir Bartle Frere, had viewed the sand dunes. This Governorskop must not be confused with a weather station near Alice of the same name. William resided here for 20 twenty years in order to tame the swirling sand dunes.

Sir (Henry) Bartle Frere, Govenor of the Cape Colony

Employing up to 300 convicts at a time, they would cut bush on the Lovemore’s Farm at Bushy Park. The branches & shrubs would then be carted to the dunes by mules or ox-wagons where they were spread with the stems pointing westward. Large quantities of willow and waxberry seeds were then scattered amongst the branches on the dunes. This exercise was performed by William Webber & his sons wearing special aprons with seed pockets.

By 1890, the Harbour Board’s reclamation scheme had proceeded to the vicinity of the Willows, still leaving vast areas of the main drift untouched.

Shark River with the Lazeretto visible

By this time, the Harbour Board has erected four buildings, three at Schoenmakerskop, which was the main convict station, which comprised houses for the Officer in Charge of Works, a house for the Superintendent of Convicts, and rough stone huts for the convicts. An outstation at Governorskop was also constructed. William Webber and his son, Sydney Webber were in charge of both these stations.

In 1888, Dr Musgrave Eaton also became involved with the reclamation works, as did Thomas B. Hare in 1893. Thomas Hare, a very popular man, committed suicide in 1898.

Spreading refuse on the shifting sand

The Conservator of Forests takes over

In order to speed up the reclamation work and to anchor the remaining drift, the Conservator of Forests, Joseph Storr Lister, was drafted in to assist Webber. This must surely be a misnomer as there were no forests and secondly nothing was being conserved. On the contrary, the dunes were being emasculated, defiled of their will-o-the wisp beauty.

On the 23rd September 1890, Joseph Lister submitted a report to the Harbour Board. In it, Lister made proposals to combat the “menacing” drifting sand. After being adopted in a Council Meeting during 1892, a start was made on the reclamation work.

Of all the early maps of the driftsands, this is the most accurate

By 1893, the farms and lands, which were necessary to expropriate, had been purchased. Once they had been transferred to the Government, the work to halt the moving sand was taken over by the Forestry Department. It was at the point that the original farms de Fontuin and Gomery as well as part of the Old Fishery became Crown Land.

Frederick Korsten owned a whale fishery in 1821 known as the Fishery on the beach adjoining Strandfontein. As there was no access to The Fishery on the beach adjoining Strandfontein, due to the sand dunes preventing movement, instead, access was gained via an inland road known as Fishery Road. The road followed roughly the current Walmer Road/ La Rochelle Drive. Eventually all the buildings at The Fishery were engulfed by the drift sands.

Papenkuilsfontein or Cradock Place

In order to hasten the reclamation work, a refuse train with the sobriquet “The Driftsands Special” was used to transport 80 tons of PE’s rubbish on a daily basis to the driftsands. This detritus of civilisation was scattered all over the remaining pristine drift sands area. While this work was in progress, a party of convicts was employed to complete the barricades at Gultchways and to maintain this barricade against further stealthy incursions from the west.

Governorskop was the terminus of this refuse train, which operated from the rubbish tip at South Beach Terrace, through the dunes to Schoenmakerskop. It goes without saying, that the train was accompanied by huge dense swarms of sticky buzzing flies. To the Conservator of Forests and his team of convicts, it was merely an occupational hazard, which had to be endured and ultimately ignored.

Schoenmakerskop

Finally, circa 1910, the services of Joseph Lister, his team of convicts as well as The Driftsands Special service were all terminated.

Victory at last

The progress of the extensive rubbish-dumping scheme gradually came to an end as the whole area had been covered with rubbish.

The 30-year campaign to conquer the drifting sand was won. No more would nature prevail and decide whence it would travel and where it would form mounds and runnels. Man had been triumphant.

Development comes at a price and that cost is born by nature. In Port Elizabeth’s case, it was the irreparable destruction of a vast swath of drift sands within its own ecosystem to be replaced with exotic plants and vegetation such as the willow. Moreover it was not merely the drift sands that paid the price, but also the abundant sea life and the herds of game that roamed across the Kraggakamma area.

Such is the price that progress demands.

Remnants

The track taken by The Driftsands Special is still visible today. Opposite the entrance to the Municipal Pump Station on the road to Schoenmakerskop, was a long avenue of blur gum trees. This marks the TDS’s track. In close proximity to the train-line was a low wall of corrugated iron. The wall was approximately two to two and a half feet in height. Its probable use was to hold back the sand. This wall continued in a north westerly direction past the present pump station and reservoir.

The Trig beacon at Chelsea Point

Years later from about 1970 to 1980 old bottles and other interesting items could be salvaged from the large dumping area, even pieces of coal from the Driftsands Special. During these years, sellers were a common sight on the roadside with bottles, lids and ornaments on display, all from a bygone era.

Footnote

Apart from the taming of the sand dunes, the construction of the eastern breakwater in the harbour has prevented the cycle of sea sand within Algoa Bay itself. Instead of following its age-old migration route around the Bay, it has accumulated against the breakwater itself.

Aerial view of harbour showing the sand accumulated against the breakwater over the years

Related blogs:

Port Elizabeth of Yore: The Holy Trinity Church in Havelock Street

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Schism in St. Mary’s creates the Holy Trinity Church

Port Elizabeth of Yore: St Phillips Church on Richmond Hill

Port Elizabeth of Yore: St Phillip’s Church on Richmond Hill

Port Elizabeth of Yore: St. Mary’s Cemetery

Mosenthals: A Metaphor for the Fortunes of Port Elizabeth

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Brickmaker’s Kloof

Port Elizabeth of Yore: The Eponymously Named Brickmaker’s Kloof

Port Elizabeth of Yore: The Enclosed Harbour Scheme in the 1930s

http://thecasualobserver.co.za/port-elizabeth-yore-enclosed-harbour-scheme-1930s/

Port Elizabeth of Yore: The Harbour prior to the Charl Malan Quay

Port Elizabeth of Yore: The Harbour prior to the Charl Malan Quay

Port Elizabeth of Yore: St Mary’s Church

Port Elizabeth of Yore: New Church in Main Street

Rations, Rules and other Regulations aboard the Settler Ships

Rations, Rules and other Regulations aboard the Settler Ships

Port Elizabeth of Yore: The Earliest Photographs

Port Elizabeth of Yore: The Earliest Photographs & Photographers

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Empire units in P.E. during the Boer War

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Empire units in P.E. during the Boer War

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Defences during the Boer War

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Memorials to the Fallen in War

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Fire Damage to the P.E. Advertiser in 1913

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Fire Damage to the P.E. Advertiser in 1913

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Albany Road

Algoa Bay before the Settlers: Sojourn by Henry Lichtenstein in the Early 1800s

Algoa Bay before the Settlers: Sojourn by Henry Lichtenstein in the Early 1800s

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Captain Jacob Glen Cuyler

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Captain Jacob Glen Cuyler – A Man of Many Parts

Port Elizabeth of Yore: The Growth of the Population

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Murders most Foul

Port Elizabeth of Yore: The Phoenix Hotel

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Echoes of a Far off War

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Main Street in the Tram Era

Lost Artefacts of Port Elizabeth: Customs House

The Great Flood in Port Elizabeth on 1st September 1968

Port Elizabeth of Yore: The Great Flood of 1st September 1968

A Sunday Drive to Schoenmakerskop in 1922

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Horse Drawn Trams

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Trinder Square

The Sad Demise of the Boet Erasmus Stadium

Interesting Old Buildings in Central Port Elizabeth:

The Shameful Torching of Port Elizabeth’s German Club in 1915:

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Shameful Torching of the German Club in 1915

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Cora Terrace:

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Cora Terrace-Luxury Living on the Hill

Port Elizabeth of Yore: The Grand Hotel:

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Whaling in Algoa Bay:

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Whaling-From Abundance to Near Extinction

Port Elizabeth of Yore: White’s Road:

Port Elizabeth of Yore: The Slipway in Humewood:

Port Elizabeth of Yore: King’s Beach:

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Russell Road:

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Russell Road-Formerly Burial or Hyman’s Kloof

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Sand dunes, Inhabitants and Animals:

Port Elizabeth of Yore: The Horse Memorial:

Port Elizabeth of Yore: Target Kloof:

Port Elizabeth of Yore: The Road through Target 3Kloof & its Predecessors

The Parsonage House at Number 7 Castle Hill Port Elizabeth

Port Elizabeth of Yore: The Parsonage House at No. 7 Castle Hill

What happened to the Shark River in Port Elizabeth?

A Pictorial History of the Campanile in Port Elizabeth

Allister Miller: A South African Air Pioneer & his Connection with Port Elizabeth

http://thecasualobserver.co.za/allister-miller-south-african-air-pioneer-connection-port-elizabeth/

The Three Eras of the Historic Port Elizabeth Harbour

The Historical Port Elizabeth Railway Station

The Friendly City – Port Elizabeth – My Home Town

Sources:

Port Elizabeth: A Social Chronicle to the end of 1945 by Margaret Harradine

Darling…would you like a string of pearls or a house at Schoenmakerskop by Joan Shaw

Port Elizabeth in Bygone Days by JJ Redgrave

1 Comment